Post by Frank Bramblett

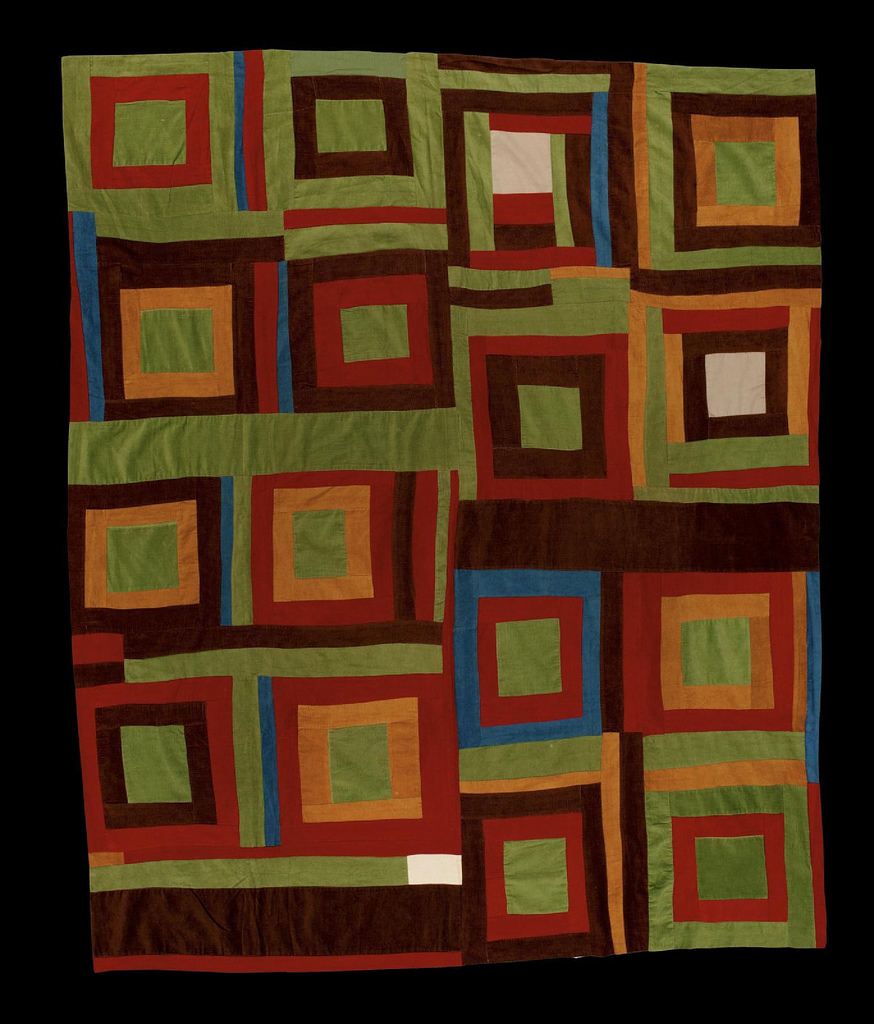

Earlier today, I heard a short public interest story on the radio to draw attention to the PMA exhibition that opens today, Gee’s Bend, the Architecture of the Quilt. When I first stood before the quilts in 2002, I was astounded. But I knew not why the work possessed such power, and their presence has haunted me since. The radio pro-mo mentioned something of the history of Gee’s Bend that I was unaware of. Hearing this story prompted me to read more about that history.

What I learned about the individuals that made the quilts led me to a desire to share their story. Their story is a part our history as a nation, and very much a part of my history. Hearing and reading about the history of Gee’s Bend has offered to me a way to understand why I am who I am now. Hearing and reading their story has given me clarity as to why I see this time as a critical moment in our history.

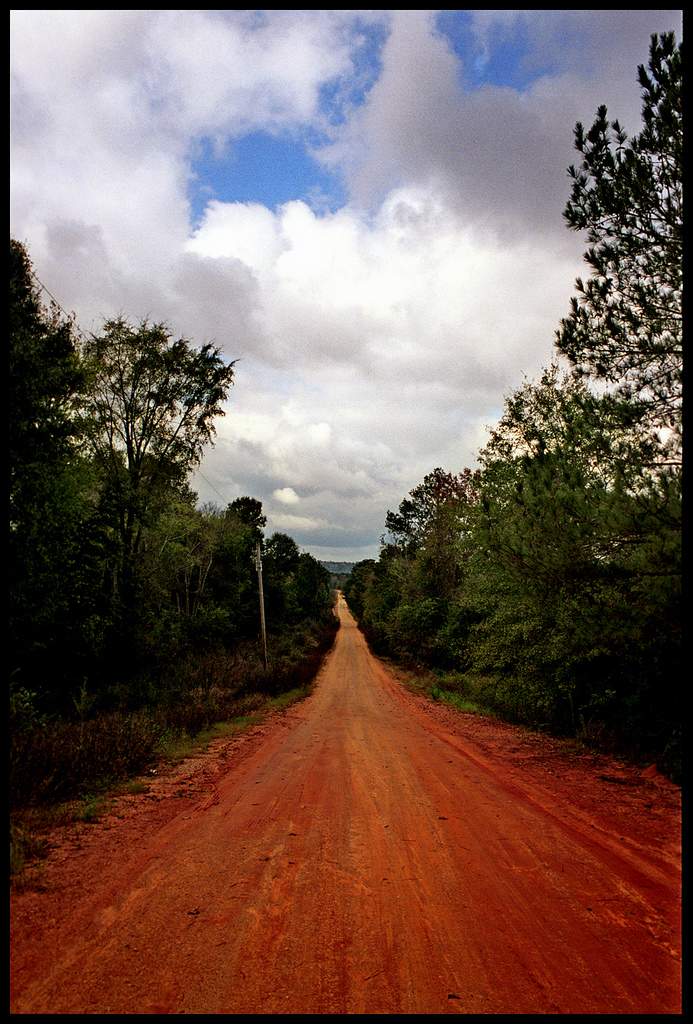

The story that I heard and read is about a small town in southwest Alabama, Camden, and a community that is visible across a wide river, Gee’s Bend. The small community of Gee’s Bend bears the name of a former plantation, and is populated by sharecropper descendents of the plantation’s slaves. The community had been surrounded on three sides for 200 years by the river with the town of Camden being the only nearby town.

There were two ways to travel from Gee’s Bend to Camden; a ferry that was an easy walk and that took 15 minutes; and a trip of an hour on bad roads … if you had one of the very few cars. In Gee’s Bend there were no businesses. In the nearby Camden were all of the necessities for living–clothing stores, grocery stores, a drug store, a post office, a fire department, schools, doctors, a hospital, and jobs.

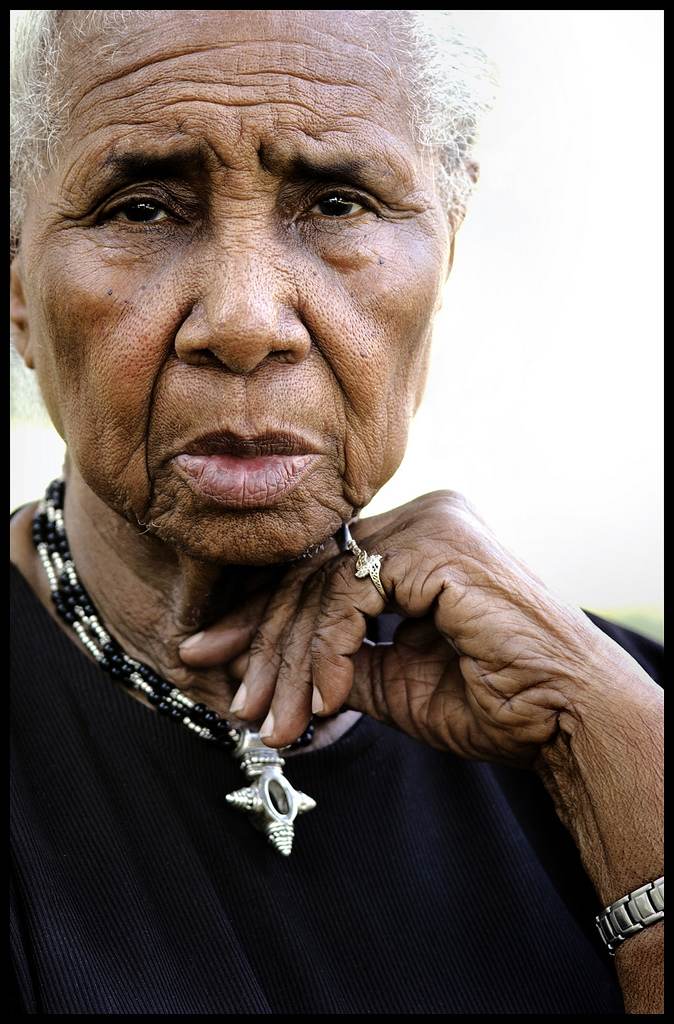

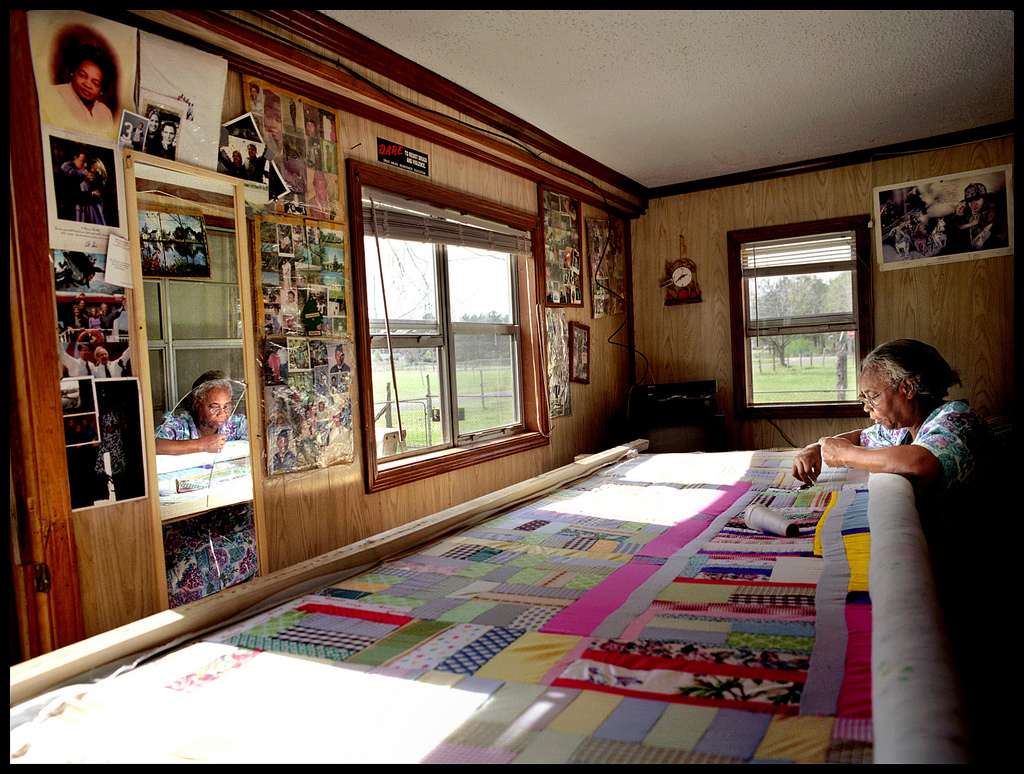

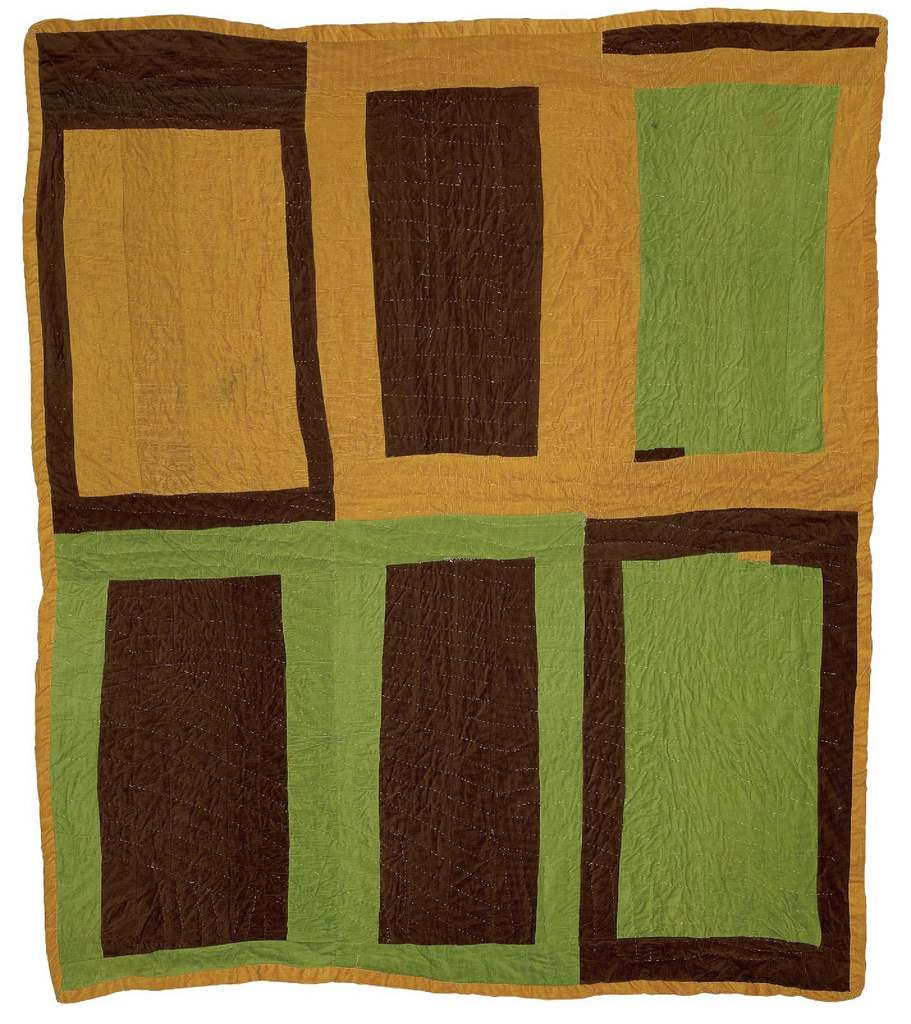

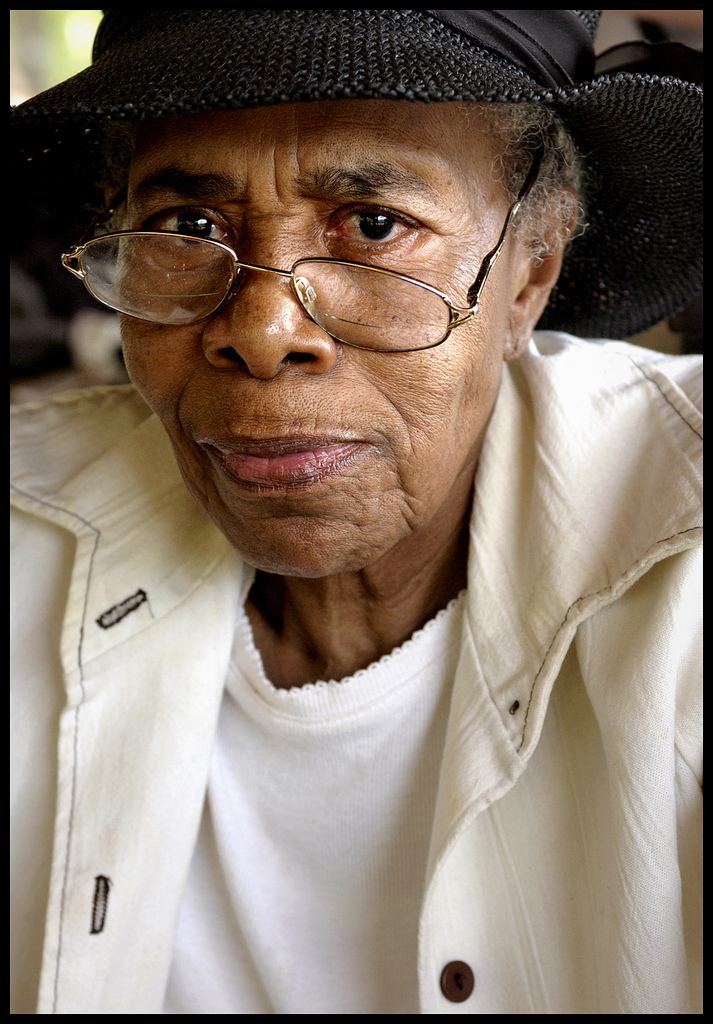

In the early sixties the people of Gee’s Bend become involved in the Civil Rights Movement, and organized public protests against segregation in Camden. In 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Gee’s Bend to support the cause of the people, to speak of freedom and equality, and to lead a voter registration drive. National attention was focused on the town and the citizens of Gee’s Bend. As one 90-year-old resident of Gee’s Bend recollected, “When you leave home that morning to go march, you didn’t know if you were going to make it back home or not.” We were “met with intimidation and intolerance.” Hollis Curl, a former Camden town leader and a judge who had published an article in the local newspaper in support of segregation said about those times. “No matter how hard the racists tried, they couldn’t stop the growing tide of change.” “Marching and demonstrating in the street and holding voting rallies…some of the movers and shakers in the county at that time wanted that stopped.” The citizens of Camden could not stop the protest. Tension quickly escalated between the communities. Following one of the organized protest marches, 410 protesters were put behind bars. Following Dr. King’s visit, Camden’s white leaders realized they they couldn’t stop the protests, so they would take another action; “to keep the agitators from coming across” they stopped running the ferry one night without alerting anyone in Gee’s Bend. Overnight, the cast-aside community became a virtually isolated island. Immersed in poverty, the proud women who once labored as sharecroppers sat down at quilting bees and “stitched their prayers into intricate tapestries”.

In 2002, the Quilts of Gee’s Bend opened at the Houston Museum of Art. By the time that the exhibition opened at the Whitney in New York later that year, demand from other major museums to show the work was unprecedented. Six years later, portions of the original exhibition along with additional or other quilts continue to travel the world in the form of this exhibition. As Gee’s Bend had national attention in the sixties, the community was once again drawing national and international attention as its quilts have been deemed a treasure of history, a story of our culture, and masterworks of art. The work of the artists of Gee’s Bend has been chronicled in exhibition catalogs; newspaper and magazine reviews; television coverage; documentary films; audio recordings; and in books including a comprehensive history of Gees Bend that is being released this week [Frank wrote this Sept. 19]. The women of Gee’s Bend are now international travelers; have held concerts at major concert halls; have had a play written about their history that is on tour (currently at the Arden Theater in Philadelphia); and their work is in great demand and represented by major galleries.

In 2006, former Judge Curl was sitting on his deck over the river and watched as a house burned in Gee’s Bend. As Gee’s Bend had no way to fight the fire, he later petitioned–“to have the ferry returned due to his remorse”. After 40 years, the people of Gee’s Bend were no longer isolated.

When the events of the early sixties were happening in Gee’s Bend, I was growing up across the state of Alabama in the small town of Wedowee. As I read about the place and the people of Gee’s Bend, it was like a mirror looking into memories of experiences in Wedowee as a boy, and of encounters in my upbringing. I remember things that I heard around town that made me feel uncomfortable at the time. I remember the fuzzy images on our black and white television of events across the state. I remember the stories of those tumultuous times, but the name of the town of Gee’s Bend had escaped me. As I read, I asked myself why had I buried those memories?

If you listen to the voices of Gee’s Bend in any of the many videos or audio documentaries, the women have remained proud throughout the decades since those troubled times; and they have maintained their dignity because they had fought for their civil rights so long ago. And it is clear in listening to those voices that they realized that the long isolation of their community from the public resources of the nearby but inaccessible town was not their loss. Their loss was that the civil rights that they had fought to attain had been taken away when the ferry stopped. But the greatest insult as citizens was their loss of the right to vote.

When you stand before the quilts of the women of Gee’s Bend, do not forget their story. What you will see are the shapes, colors, textures, patterns, and stitches, but what you will sense is the profound meaning beneath the surface of their beauty. What you will not see is their intention to make art, but what you will see is the life that made the quilts become art. It is not the remorse of Judge Curl that has given the women of Gee’s Bend back the ferry. Their ferry was returned because of what is represented in the lives and the stories that are held within their quilts. It is the power of what is contained within their art that has given to them their civil rights. Can any art be more politically powerful?

Like Pennsylvania, Michigan is one of the hand-full of “swing-states”. Economically Michigan is the nation’s hardest hit state, in part because of the effects of current government policies. An organization with an allegiance to a political party has ferried to that party’s polling officers across Michigan a listing of what has been stated as a number approaching 180,000 former homeowners whose houses have been foreclosed. As it is required that you must prove legal residency in order to vote, it is the intention of those that hold this listing to deny the right to vote to the citizens on that list. Assuming that most houses have an average of two residents, this effort potentially affects the voting rights of as many as 360,000 citizens. As with similar situations in recent elections by people of like minds, this kind of practice causes delays, frustrations, and many denials of voting rights. The competing party is aware of this and of other planned attacks on voting rights, and is bringing legal action. But there will be other efforts to disenfranchise.

As I read today, I felt a chill through my being. What had happened to the citizens of Gee’s Bend over forty years ago has never ended. We as a people are in much the same place as we were when I was a boy; only we have learned to be more devious in our methods of resisting a culture of human decency, and of civil rights that is the fundamental promise of our democracy. This election is not about the “war”; it is not about the economy; this election is not even about the presidency. This election is a referendum of where we are as a nation.

Frank Bramblett

September 16, 2008

–Artist Frank Bramblett taught painting at Tyler School of Art. He died in September, 2015, and is very much missed.