Lenape umbilical cord bag made of leather, beads, quills, wood and plastic, circa 1952. Children’s umbilical cords are often kept in special bags. This bag in the shape of a turtle is decorated with traditional Lenape quillwork. The beading on its back represents the story of Turtle Island. Photo: Lauren Hansen-Flaschen.

Fulfilling a Prophecy; the past and present of the Lenape in Pennsylvania at the Penn Museum

The first information in Fullfilling a Prophecy at the Penn Museum (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, on view through September 13, 2009) is the wall text stating there are no federally recognized tribes resident in the states of New Jersey and Pennsylvania according to the U.S. Department of Interior. Since nearly half of Native American groups are unrecognized by federal or state authorities, this might not be so meaningful but for the widely-told story that all of the Lenape were forcibly displaced from the East coast after 1778 when they signed a peace treaty with the U.S. government and were tricked out of their land; many moved to Oklahoma or Wisconsin where Lenape tribes are recognized.

A Lenape fan made of beads, deerskin and feathers rests in the hands of Shelley DePaul, Director of the Language Program for the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania and a co-curator of the exhibition. The fan which is a recent gift to Ms. DePaul is rich in Lenape symbolism.

Pennsylvania Lenape who chose to remain were forced to hide their identity; this is their story. They intermarried with Germans, Mennonites, Quakers, Amish and runaway African slaves, all the while holding onto tribal culture in secret, much like the Jewish conversos (Marranos) in Catholic Spain. They maintained their secrecy until the birth of the American Indian movement in 1968 (a manifestation of the civil rights movement), and this exhibition was organized as an attempt to overcome long held Euro-American misunderstanding of their culture. It is a tremendously moving story.

The history of Lenape survival is told via the Prophecy of the Fourth Crow, a traditional Lenape tale. The First Crow is interpreted as the Lenape before the Europeans arrived; the Second Crow is the destruction of the culture. The Third Crow is the people going underground and hiding, while the Fourth Crow is resumption of their traditions and working with others to restore the land.

Replica of a doll made in the 1940s by a Lenape woman for her granddaughter. On the back of the doll’s head, the grandmother stitched a second, hidden face to teach the young girl to keep her heritage a secret. Photo: Lauren Hansen-Flaschen.

Since Lenape material culture is primarily made of organic materials (wood, bone, skin, plant materials) most archaeological evidence of the past has been lost, although the exhibition includes photographs of several remaining circular stone huts. The historical information comes from Lenape oral history and from early European accounts. The artifacts on view are reconstructions according to traditional methods and have been lent by tribal members. One mask (c. 1800) was allowed on view since it had been ritually retired. A small pouch containing an umbilical cord (above) is a Lenape adaptation of a custom from another tribe; Lenape culture continues to evolve, as does ours. But the exhibition is much more than the modest collection of artifacts; it is a correction to history and an affirmation that the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania survives.

Exhibition curators Chief Robert Red Hawk Ruth, Shelley DePaul and Abigail Seldin take a look at some of the Lenape objects in Penn Museum’s collections storage. Photo: Lauren Hansen-Flaschen.

And here is a second story of interest, for the exhibition was curated by Abigail Seldin, a graduate student in anthropology at the U. of Pennsylvania, working with Chief Robert Red Hawk Ruth and Shelly De Paul, both members of the Pennsylvania tribe; it is the result of a true collaboration, which is noteworthy. That the museum has given up its stance of academic authority and allowed the subjects to present themselves reflects the most current ideas about museums, ideas often acknowledged but rarely enacted.

Followers of contemporary art are well aware of the institutional critique of museums conducted by artists such as Marcel Broodthaers, Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren, Andrea Fraser, Fred Wilson and others as well as by numerous theorists. It has raised questions of who was speaking for whom and to whom, and rejects the model of museums as secular temples removed from everyday reality. Some museums have responded, usually by allowing the artists to voice their ideas within institutional walls; but the acknowledgment has rarely gone much further. Perhaps anthropology and archaeology museums have responded more significantly than art museums; the Penn Museum certainly has.

Protection of Indigenous Cultural Heritage

Two days after visiting the Lenape exhibition I returned to the Penn Museum for another immensely moving occasion: the first public event of the new Penn Cultural Heritage Center (attached to the Penn Museum and the University), which by its own description is dedicated to expanding both scholarly and public awareness, discussion, and debate about the complex issues surrounding the world’s rich—and endangered—cultural heritage. The public conversation addressed cultural heritage and indigenous communities; participants came from five days of study at the Cultural Heritage Center aimed at broadening the discussion of repatriation of museum objects. They represented Kechua, Cheyenne, Yucatec and Kechin Maya, Mapuche, Cuna and numerous other indigenous groups from Alaska and British Columbia to Hawaii, and Panama to Argentina.

Chief Robert Red Hawk Ruth, representing the local people, opened the event with a prayer in Lenape; the talks were in English and Spanish, with a few further blessings and greetings in indigenous languages. While the participants had not known each other before the previous five days, they found they shared many common concerns and relations with their respective governments. The word that ocured most often was respect. Their overall message was that they are alive and represent living cultures; and they have much knowledge to share.

Their understanding of cultural heritage is much broader than material culture: language, song, dance and social customs are equally important and endangered, and cultural heritage is a complex concept when tribal members are increasingly moving into urban environments. These visitors have a great deal to teach us, far more than the mute objects of their tribes that are found in museums, or the distorted enactments of traditional rituals performed for tourists. The Penn Cultural Heritage Center has started an important conversation about the human environment that is as much at risk as the natural one, and as much in need of protection.

Another story recovered: the Africans in Mexico

The African American Museum in Philadelphia is hosting an exhibition that tells another long-overlooked story and one that should interest Americans as well as Mexicans. The African Presence in Mexico from Yanga to the Present (organized by the National Museum of Mexican Art, Chicago, on view in Philadelphia through Oct. 19, 2008) includes the history of Yanga, an escaped slave who founded the first free town in the Americas in 1610, the African-Mexican Vicente Guerrero, hero of the War of Independence and Mexico’s second president, and the belated acknowledgment of the African presence by the Mexican government in 1992, when it was termed Mexico’s third root. While primarily a history exhibition it includes original art, particularly in the contemporary section, which traces the interaction between African-Mexicans and African-Americans. There are sculpture and prints by Elizabeth Catlett, photography including Manuel Alvarez Bravo, and others.

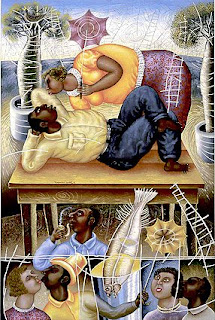

Maximino Javier (b. 1950), Indecisive Chacmool (2002) oil on canvas