Aaron Douglas; African American Modernist at the Schomberg Center, NYC

Aaron Douglas was the major painter of the Harlem Renaissance, yet most people who recognize his name probably only know his work in reproduction. Douglas’ first traveling retrospective, representing all of his mural projects as well as easel paintings and illustrations, is making its final stop at the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library branch at 135th St. through Nov. 30, 2008 (the Schomberg is easy to reach; the 2 and 3 train stop is about 20 feet from the door). Everyone interested in American art history should rush to see it. Organized by the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, its venue at the Schomberg is appropriate since the building houses Douglas’ most accessible mural project, Aspects of Negro Life (1934); but I still can’t understand why by 2008 his work has not made it to institutions further downtown.

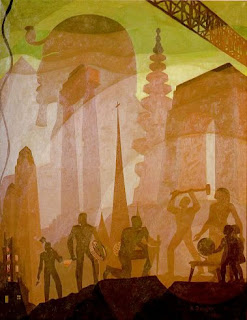

Aaron Douglas Build More Stately Mansions (1944) oil on canvas, 54 x 42 in, Fiske University, Nashville

Douglas studied with the Munich-trained modernist Winhold Reiss, whose own work drew from popular and commercial sources such as German folk paper-cuts (scherenschnitt); Reiss encouraged Douglas to do the same, and he developed a style of elegant, rhythmic silhouettes that he adapted for his great mural cycles as well as in graphic work. During the 1920s Douglas worked with many important writers of the Harlem Renaissance on small publications, on dust jackets for their books and collaborating on portfolios, such as Opportunity (1926) with Langston Hughes.

Aaron Douglas Play de Blues (1926), from Opportunity, portfolio by Langston Hughes with illustrations by Douglas

Douglas’ signature painting style of layered silhouettes within a narrow chromatic range and emphasis on radiating circles of light certainly owes something to spot lighting of the stage or more likely film, particularly that of the German expressionists. The only other American painter whose work belied the influence of Expressionism this early was Marsden Hartley, who spent time in Germany prior to World War I. Douglas’ more significant contribution to art was his subject matter: the history of African-Americans which includes the indignities of slavery and horrors of lynching as well as their economic, cultural, intellectual and artistic contributions to American life. His artistic legacy is reflected in the work of Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, the AfriCOBRA artists, Faith Ringgold and others; certainly the heroic silhouettes of Kara Walker which rewrite slavery in America are his most recent bequest.

The exhibition begins with a painting by his teacher, Reiss, includes all of the mural projects (even if those at Fisk University are shown only in video form), easel paintings, all the book jackets and numerous illustrations. It also includes work by several artists influenced by Douglas, although not the strongest selection. The hanging at the Schomberg is limited by its division in two spaces, neither of which is ideal for the large pieces. But it’s a significant opportunity to see his much-dispersed oeuvre, and shouldn’t be missed.

Salvatore Meo; Assemblages 1948-1978

Salvatore Meo Tyler School (1946), mixed media, 25″ x 15″ x 2″

Salvatore Meo has slipped through the net of mid-Twentieth century American art history. Fortunately the exhibition of his work currently at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, University of the Arts (through Nov. 26, 2008) makes a compelling case for mending that state of affairs. Meo made assemblages from the sort of detritus that Rauschenberg would include in his combines of 1954-64, George Herms and Bruce Connor would incorporate into sculpture in the late 50s-early 60s, and the Italians associated with Arte Povera employed during the late 60s-70s. But Meo, who studied and worked in Philadelphia then moved to Rome in the 50s began using scavenged, abandoned objects in the 1940s. He constructed his work from fragments of furniture such as a dresser drawer with chipped paint, scarred wood with protruding nails, the dirty head of a small doll, a work glove with fingers worn through, one heel of a woman’s shoe, a fraying bit of cloth. He knew Alberto Burri, Mimo Rotella and both younger and older Italian artists Rome, and may actually be a progenitor of Arte Povera.

It’s impossible to know where the idea of using such thoroughly rejected material came from. There’s no American precedent except for a handful of collages by Arthur Dove from the 20s, and in Europe only Schwitters, Dubuffet and Miro come to mind. Cornell’s work is too precious to be considered as inspiration, and Nevelson thoroughly transformed her found fragments of wood with monochrome surfaces of paint. Certainly there’s a debt to Surrealism (when he incorporates sand its impossible not to think of Masson), but even at their most outrageous the Surrealists retained the legacy of craft that Meo suppresses.

Salvatore Meo Loretto (1954), mixed media, 26 1/4″ x 29 1/4″ x 6 1/2″

But chronology apart, Meo’s work deserves attention because it is so good. He picked through gutters and junkyards, using objects seemingly as he found them and assembling them with a master’s eye. He drew with twisted wire, created washes of bent mesh and used the folds of crushed metal to create structure in small wall pieces of subtle balance and formal tension; they acknowledge Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on the spontaneous and even the accidental. His work tends towards the limited pallette of the well-worn: browns and grays; but when he incorporated colored bits he did so as punctuation, with assured restraint. His process might be seen as a modern parallel to Leonardo’s suggestion that artists exercise their imagination by finding figures in clouds or broken walls, although Meo was searching not for figures but for the building blocks of abstraction.

Salvatore Meo Speranza (1951), mixed media, 32 ½” x 32 ½” x 5″

While Meo’s materials rarely evoke specific metaphorical interpretation, it’s hard not to see his entire production as an attempt to rebuild a world of meaning out of the ruins and destruction of World War II. He served in the South Pacific and while there is no indication that he saw the results of Hiroshima or Nagasaki first hand, they could not have been far from his consciousness; nor could he have ignored the legacy of destruction in Italy. In recycling cast-off objects Salvatore Meo assembled them into poetic art. Meo produced a significant body of work, and it is good to welcome it back into the American art world.

Another exhibition of Meo’s work will be shown at Pavel Zoubok Gallery in New York from Nov. 13-Dec. 20, 2008.