This week’s Weekly has my review of the Lewis Tanner Moore collection exhibit In Search of Missing Masters at Woodmere. Below is the copy with some photos. More pictures at flickr.

Claude Clark, We Are Sisters, 1949

Lewis Tanner Moore’s collection of African-American art, on view at Woodmere Art Museum, is chock full of great work by artists whose names you’ve probably never heard and whose art you’ve probably never seen.

Raymond Steth, Institution Series #1, 1980. lithograph

African-American artists are often excluded from the mainstream art world. A local collector and the grandnephew of Postimpressionist painter Henrey Ossawa Tanner, Moore grew up surrounded by art. But he noticed there was no connection between the art he saw at home and the art he saw in school.

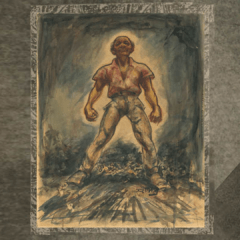

Dox Thrash, Sunday Morning. @ 1939 etching

Catalyzed by this realization, the youngster organized an exhibit of African-American art at his high school in 1969 with borrowed works. The show was a turning point for Moore, who said it was “the moment at which art became the organizing force in my life.”

“In Search of Missing Masters,” the 100-work show organized by Woodmere’s curator of collections Douglass Paschall, includes academic figure and landscape paintings and sculpture, expressionism, African-influenced totems and grafitti-esque abstractions. It’s an unabashedly humanist show with many images that evoke people doing everyday tasks. All this comes in many small works that pack big visual moments.

Installation shot with James Brantley’s painting (top), Louis Sloan (middle) and Leo Robinson (bottom)

Take James Brantley’s painting Man with a Horn (1996). Imbued with an otherworldly quietude and optimism, the work—which shows a group of people in a desolate landscape—raises thoughts of Moses’ monumental journey through Egypt. Conversely, Barbara Bullock’s cut paper Ethiopian Winged Figure (1995) is all grace and joy.

Another noteworthy piece in this show is Donald Camp’s photograph Brother Who Taught Me to See—Herbert Camp (1992), which shows the sober face of a man of experience. The aging visage of Herbert Camp in the distressed photo is a document of a life.

The late Claude Clark’s impastoed painting We Are Sisters (1949) (top image) is an almost cartoonlike profile portrait of two women: one black, one white. The work is fresh in its style and paint handling and hopeful in its sentiments.

Installation shot with William t. WIlliams’ piece above Charles Burwell’s.

Hung salon-style, the show groups works to make comparisons come to life. William T. Williams’ calligraphic Monk’s Tale (2006) sits above Charles Burwell’s Bio Labyrinth #9 (1997). Williams’ fugue of dancing white curlicues on a black ground is as optimistic as Burwell’s ominous petri dish image is perturbing.

The big show has a beautiful catalog with full color reproductions of the works.