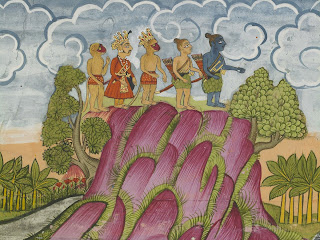

Rama’s Army Crosses the Ocean to Lanka from the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsidas (1532-1623), Jodhpur (ca. 1775), opaque watercolor on paper, 63 x 125.8 cm, Mehrangarh Museum Trust. The scene displays continuous narrative with Rama, at upper left, planning the crossing from a mountaintop then at center left, prior to the crossing and a third time, at the center of a stone bridge as he is carried across the ocean on the back of a monkey warrior; finally he is seated as he speaks to his assembled army of monkeys and bears on the far shore.

One enters Gardens and Cosmos: the Royal Paintings of Jodhpur under a large floral tent canopy that the maharajas of Marwar used when away from home; its floral embroidery recreates the gardens they cultivated at their palaces despite the fact that their kingdom was at the edge of the Thar Desert. The exhibition, on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution through Jan. 4, 2009 prior to an international tour, consists of sixty paintings made for the Marwar court in the 18th-19th centuries. The court flourished under the Mughals and the painting is an amalgam of local traditions combined with the refined elegance of Mughal court style. These recently discovered works have never been published or exhibited and look like nothing seen before. While the most of the figures are on the scale of miniature paintings they were painted on paper up to four and a half feet long.

detail of Rama’s Army Crosses the Ocean to Lanka (seen above); the blue-hued Rama plans the crossing from a mountain top.

Much too large to be held in the hand for intimate viewing, the monumental manuscripts needed someone at either end to display them, likely for group viewing while sacred verses were recited. Such use of pictures to support storytelling is common in Indian popular art (I saw a demonstration by Gujarati performers at Philadelphia’s International House last year), but less well know in court culture and no documents record the display or use of the Marwar paintings. The large scale forced the artists to create panoramic compositions of life at court and religious narratives; the most lively illustrate Rama and Krishna in sacred landscapes and in battles with demons. As with Western artists who found Hell a more interesting subject for invention than Heaven, scenes of battle or violent monsoons command the most attention (image and detail above). In an episode of Rama’s army crossing the ocean to Lanka, where the demon Ravana lives, layers of threatening storm clouds roll across the sky and herons flee from the impending battle, monkeys swim across the ocean and hitch rides on the backs of alligator-like creatures and an army of monkeys and bears cross a bridge on their hind legs.

The paintings done for Man Singh, the last maharaja before British rule, display an extraordinary imagination for theological subjects. Man Singh was a follower of a branch of Hinduism run by ascetics, the Naths. A central Nath tenet is the Absolute, known as Brahman, a transcendent essence from which the universe derives. A formless, all-encompassing deity poses the same problem for artists of all faiths, which is why the rare portrayals of the Trinity with a fully-anthropomorphized God the Father usually look rather silly. Such deities are rich subjects for poetic description but impossible for visual artists, who usually restrict their representations to embodied deities. But Man Singh’s artists ingeniously represented the ineffable as an un-inflected gold ground. The sparkling expanse of actual gold sometimes fills an entire frame; in other scenes the gold is ground for figures representing manifestations of the cosmos in perceptible forms (see above). It is a breathtaking conceit and intriguing to viewers who are aware that spirituality was one early justification for European abstraction.

Cosmic Ocean, one of seven folios from the Nath Charit, attributed to Bulaki (1823), Samvat 1880, opaque watercolor on paper, 44.1 x 118.2 cm, Mehrangarh Museum Trust. Three perfected beings within a vast, swirling ocean make a gesture with one raised hand; one sits astride a figure on an antelope, another sits on a snake. This is one of seven related esoteric paintings whose exact meaning is unknown.

The exhibition includes detailed depictions of court life and architecture (portrayed with the same hieratic scale as the figures, so palaces and religious buildings dwarf buildings beyond the royal precinct), religious narratives, sacred sites, mandalas, charts of chakras, yantras (maps of sacred geometry) and other sacred works.

The final room of the exhibition contains seven paintings whose esoteric subject remains secret: deities floating in variously-colored cosmic oceans of rhythmically rolling waves that fill most of the fields (above). Their subjects may remain locked, but their visual eloquence still speaks. The entire exhibition is a feast for all lovers of painting.

The accompanying catalog (ISBN 978-1-58834-257-7) is very beautiful with full images of all the works and numerous enlarged details which enable close study of the paintings, with their casts of thousands and minute brushwork; these images alone should provide endless interest. It also includes articles by four scholars as well as entries for each painting, and, unusually, a reference catalog of comparative material, useful for readers whose libraries lack those resources.

“Moving Perspectives: Video Art from Asia”

Yang Fudong Liu Lan (2003) still from a single-channel video (35, black and white film transferred to video), courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

The first two videos in a series at the Sackler are on view through November 30: Yang Fudong’s Liu Lan (2003) and San Yuan Li (2003) by Cao Fei and Ou Ning. Both are shot in black and white and deal with the tension between traditional life and rapid modernization in China (a parallel selected by the curator, no doubt) but are entirely different in tone and development. Yang’s is a fairy tale of lovers separated by time and changing society. The collaboration of Cao and Ou begins with a view from above of a walled city, farmland and a small, outlying village then moves at varying pace through a large city filled with contrasts of traditional hutongs and residents raising chickens on their roofs and the impersonal uniformity of modernist skyscrapers. Both films lack narrative soundtracks; the use of non-melodic music and varied, rhythmic pacing, as well as the overt documentary subject and covert metaphoric one of San Yuan Li reminded me very much of Koyaanisqatsi (1983), Geffrey Reggio’s film with score by Philip Glass. It’s impossible to know whether it was an influence on the Chinese filmmakers or whether they arrived at such a similar idea by another route.