Down by the muddy banks of the Thames, in weather only life boats take to the sea in, we waited for Antti Laitinen, a Finn, to set sail on his island. The Thames raced beneath the Albert Bridge in a muddy flow, and all of the vessels, including what looked like an exposed rock in a B movie topped with a bamboo toupee, bobbed in time to the flow and strained their moorings.

Antti was sheltered in a barge/exhibition space, awaiting his cue, while the one-toothed poet declaimed spontaneous lines from a hydraulic lift.

I was in the middle of a show entitled “Hotel Meridian” (as in the Greenwich meridian) organized by mahony.fm a Viennese arts collective that likes to measure the way we measure things in the world. (Their latest measurement was to see where exactly Land’s End was located. Apparently there is a tunnel leading from Land’s End down under the seabed. Is the end of the land at the end of the tunnel?)

I introduced myself to Antti and shook his massive hand; he was awaiting his cue, dressed in a wet suit and street clothing. His feet were wrapped in plastic and tape in order to protect the only pair of shoes that he had brought to London. He had forgotten a spare pair in his hasty departure from Helsinki, where he had just completed a gigantic self-portrait of himself (commissioned by live herring) made by superimposing a portrait of himself over a plot of land and, like an orienteer, proceeding to trace the lines of this portrait, using a map and compass to guide him.

Physically fit and fueled by what he acknowledges as the Protestant work ethic

(Keep working) Antti is engaged in self-measurement — the self measured against the self and the self as measured against the natural world. Whether it be turning on a treadmill and drawing with his sweat, digging holes and measuring the time it takes according to the rocks he finds, or building his own island, Antti demands physical as well as artistic accomplishment from himself. It’s a celebration of limits measured not in terms of height or distance but in terms of a physical artistic self. Antti is dancing. He is choreographing his movements and actions and creating his own props. Winning isn’t the key; rather it’s a celebration of human force wearing art’s clothing (although Antti likes being in the buff whenever possible. He’s a Finn after all). The strongest components of the work are the limits to it.

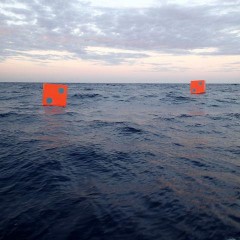

Antti disappeared, and when next I saw him he was rowing valiantly against the stream

in the light of the Albert Bridge, a 19th century steel suspension bridge lit up like a Merry Go Round. A nearby tug shined a spotlight on him.

We were a small group gathered on a bridge just above the island that appeared to remain still. Although Antti intended to navigate his land shaped yacht it truly appeared as if he was stuck on an exposed piece of riverbed that he had converted to a rowing machine.

A row, row, row his island vigorously against the sea. Merrily, merrily, merrily life is a lot of work.

The older actress to my left loved it for all sorts of reasons that she couldn’t actually say and everyone yelled encouragements. I hollered for him to go with the flow. After all what the tide taketh out, it often bringeth back in. The actress warned me to watch out or he might just make it back to land and whack me with an oar.

After about 15 minutes Antti was still pulling handsomely but the crowd was begging the man who had isolated himself on a desert island to come back into the fold. We love to watch the absurd and then it worries us. Antti and his island were pulled to the dock by lifeline.

It was a nice open piece of work that left plenty of room for the metaphor machine to start cranking. Suffice it to say that a wonderful opportunity to drift away was countered by a fiery passion to get back home. Just above Antti the cars were jammed on the boulevard while Antti, tethered to the dock, was space walking or perhaps feeling like he was on the edge of a waterfall whose edge was just where the light faded into darkness.

Antti is careful not to explain too much what is going on and we can be grateful for that. As if it mattered, earlier I had asked Antti what he was trying to do. He said that

he wanted people to see an island going by and wonder at it. Given the time and place I would have perhaps entitled the piece “Know Thine Elements”. But in daylight the Antti island would certainly elicit fascination from afar.

As the island approached the dock I noticed what appeared to be seaweed undulating along the waterline only to discover upon helping to heave the sarcophagus shaped from the sea that it was the loose ends of the island’s burlap skin, which had been trailing in the current. Drink time was declared. And flushed with post-sport delight, Antti would be the flame of the night burning bright.

Max Mulhern’s last report for Artblog was on Marc Quinn’s golden goddess, Kate Moss.