Post by K-Fai Steele

The Dreamland show in the Architecture and Design Drawings Gallery (third floor, MoMA) celebrates the 30 year anniversary of Delirious New York, written by Rem Koolhaas in 1978. The show features drawings and models dedicated to utopian experimentation since the 1970s. Unfortunately, the show was lacking in explanatory text, so one had to either have some knowledge of Koolhaas and architecture history, or be able to gumshoe information out.

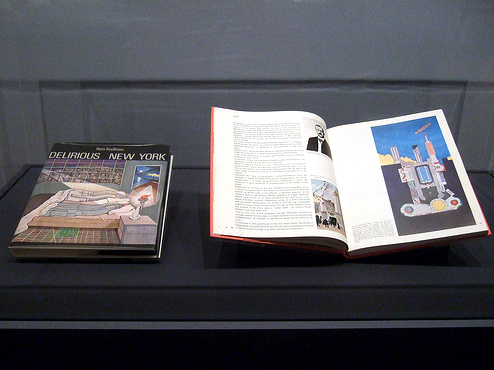

Koolhaas (b. 1944) founded the OMA (Office of Metropolitan Architecture) in 1975 with his wife Madelon Vriesendorp, and another husband and wife team, Elia and Zoe Zenghelis. The book Delirious New York, a “retroactive manifesto,” investigates New York’s fantastic architecture from the late 1800s to the early 1940s, and how the zeitgeist of New York in the industrial/post-industrial age inspired the development of utopian projects like Rockefeller Center and Dreamland in Coney Island. It is also a study of how congestion and technological advancements allowed architects to turn visions of utopia into practical use, or, as Koolhaas writes, “paraphernalia of illusion into implements of efficiency” –a relevant and active practice today.

Delirious New York, first edition copy. Cover illustration/paintings by Vriesendorp. On the right the book is open to Koolhaas’ plan of Dreamland.

From the 1800s to the 1940s, New York was an architectural laboratory for the rest of the world. New buildings were showcases of innovations such as electricity, the elevator, the telephone, and the incubator. Another invention, the “automatic baby feeder,” was shown at the Philadelphia Centennial, or the “International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures and Products of the Soil and Mine,” as it was called in 1876. The excitement of the Centennial physically moved to New York later that year when its 300-foot tower was brought to Coney Island.

Buildings themselves were architectural experiments. The Elephant Hotel was built in 1885 by James V. Lafferty. “It stood 22 feet high, with legs 60 feet in circumference. In one front leg was a cigar store, in the other a diorama; patrons walked up circular steps in one hind leg where a shop and several guest rooms were located and down the other.”

You could get a room in its thigh, shoulder, hip, or trunk, and searchlights flashed erratically from its eyes. Eventually the hotel became associated with prostitution, which prompted the local expression, “seeing the elephant”

Coney Island, circa 1886. The Elephant Hotel in the center.

Another Coney Island attraction was Dreamland, a sister to Steeplechase Park and Luna Park.

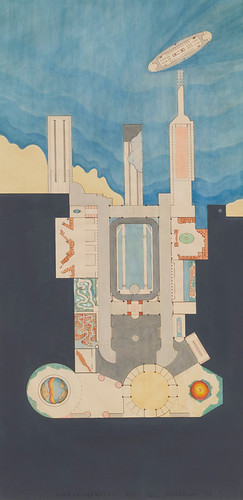

Drawing of Dreamland, 1977. Rem Koolhaas. A bird’s eye view. It is laid out “according to an intuitive cartography of the subconscious… an architectural approximation of the stream of consciousness”

One section of Dreamland was named Lilliputia and, as Koolhaas writes, “if Dreamland is a laboratory for Manhattan [and Manhattan is a laboratory for the rest of the world], Midget City is a laboratory for Dreamland.” It was a place where small scale allowed architects to experiment extravagantly.

The miniature world was populated by three hundred little people, with its own parliament, beach with “midget lifeguard” and “a miniature Midget City Fire Department responding [every hour] to a false alarm.” Koolhaas writes that it was a place of social experimentation:

“Within the walls of the midget capital, the laws of conventional morality are systematically ignored, a fact advertised to attract visitors. Promiscuity, homosexuality, nymphomania and so on are encouraged and flaunted”

Lilliputia’s fire department. Lilliputia is now the site of the New York Aquarium.

The voyeuristic display of little people is not surprising, considering the culture was shedding Victorianism. American Indians, Philippine tribesmen, and Eskimos were shown in re-creations of their native habitats, and P.T. Barnum employed a local black Brooklynite as the ‘Wild Man of Borneo.’

Manhattan, meanwhile, was expanding at such an alarming rate that a large scale, flexible structure was becoming necessary—the skyscraper. Architects envisioned buildings that would be cities within themselves.

Archigram, the avant-garde group based in 1960s London expanded the concept of an independently functioning structure with Ron Herron’s “Walking City” (1964) in which a city can move, change and sustain itself: giant, insect-like structures glide across the globe on huge legs until its inhabitants found a place where they wanted to settle. This idea has taken steps towards reality with David Fisher’s plans for Dynamic Tower (2010), “the world’s first building in motion,” an 80-story skyscraper with revolving floors (more information and an animation here.

The Metabolists in 1950s-60s Tokyo were similar to Archigram. In 1972 Kisho Kurokawa designed Nakagin Capsule Tower. It is one of the first fully modular, self contained buildings. It features pre-fab units (pods) that are fitted into a larger steel structure. Unfortunately it’s scheduled to be demolished sometime in the coming year due to asbestos concerns.

Nakagin Capsule Tower, 1972. Kisho Kurokawa. (Not featured in the Dreamland show.)

Interior, Nakagin Capsule Tower. Note the reel-to-reel in the wall unit.

The idea of an autonomous building reminded me of the high-rise, self-contained condominium complexes I saw in the New Territories of Hong Kong while visiting an uncle who lived in one of them. He said everything you needed was on the first few floors of the buildings, including a subway station. This “helps to keep people off the streets”.

The show at the MoMA includes drawings and models by some of the heavy-hitter architecture visionaries: Raimund Abraham, Hans Hollein, Stephen Holl, Peter Eisenman, and FAIA (Fellows of the American Institute of Architects).

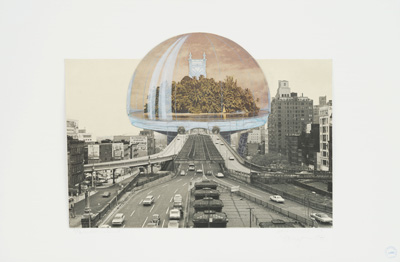

Palmtree Island (Oasis), 1971. Haus-Rucker Co.. The Manhattan Bridge.

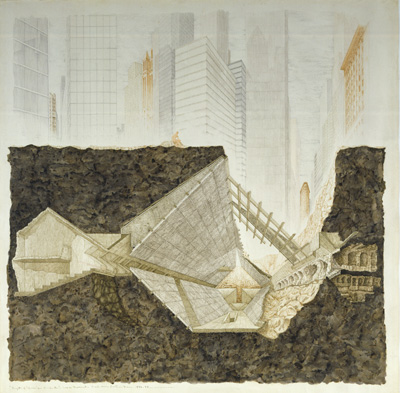

Lower Manhattan Expressway, 1967-1972. Paul Rudolph. Perspective looking east (towards Brooklyn)

Church of Solitude, 1974–77. Gaetano Pesce Antithetical to the skyscraper, similar to the World Trade Center Memorial

Bridge of Houses, 1979-1982. Steven Holl Architects. An attempt directly from 20s and 30s New York to utilize as much space as possible.

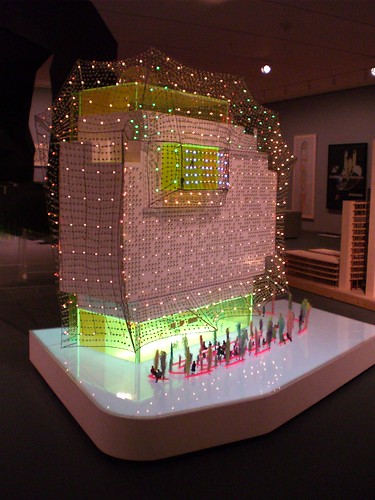

Hotel Habitat, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, 2004-present. Designed by Acconci Studio, Cloud 9, Ruy Ohtake. and Enric Ruiz-Geli.. “Your room in a tree”. The Building is encased in an “energy mesh” with red, blue, and green “leaves” which are actually LEDs on photovoltaic (solar power) cells that charge during the day. The resulting color depends on how much the cells have charged, thereby being a performing thermometer.

OMA’s most recent project: CCTV (Central China Television building, or “Big Shorts” in Beijing) to be completed in 2009.

Not included in this MoMA show, CCTV was the subject of a 2006-7 MoMA show: OMA in Beijing: China Central Television Headquarters by Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren. “…situated on a site east of Beijing’s Forbidden City, CCTV is a private building that will have a uniquely public Visitor’s Loop, while its mirror image—TVCC, or the Television Cultural Center—is a public structure housing a state-of-the-art broadcasting theater, cultural facilities, and a five-star hotel.”

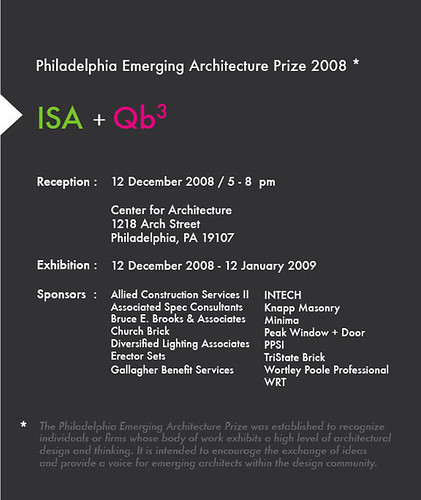

And back in real world Philadelphia, the 2008 Emerging Architecture Prize and Exhibition opened this weekend at the Center for Architecture. The show, featuring work by the winning local firms Interface Studio Architects and Qb3, runs to January 12, 2009.

This is the first year for the annual award to emerging architects. According to the website, “this Prize has been established to recognize specific works of high quality… and to encourage the exchange of ideas among emerging architects.” Shows like Dreamland and Home Delivery (earlier this summer at MoMA — see Libby and Roberta’s posts here and here) encourage utopian thinking. With all this utopian gas in the air, perhaps the emerging artists will come up with some playful utopian Dreamlands right here in Philadelphia. That would be prizeworthy.

Dreamland: Architectural Experiments since the 1970s

MoMA

to March 26, 2009.

–Artist K-Fai Steele last wrote for artblog about the Kansai Yamamoto show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.