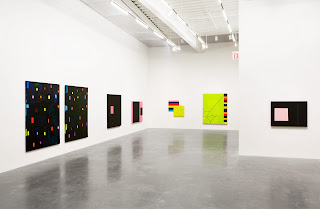

Installation of Mary Heilmann: To Be Someone; all photos courtesy of The New Museum.

I’ve been thinking about how we interact with art, prompted by yesterday’s visit to Mary Heilmann: To Be Someone at the New Museum (through January 26, 2009; it was organized by Elizabeth Armstrong of the Orange County Museum of Art). The exhibition includes not only the paintings for which Heilmann is known and a number of ceramics (reflecting her initial training) but also a number of the artist’s chairs: plywood cubes not unlike Donald Judd’s chairs (well, sufficiently unlike to be his worst nightmare; these have wheels, webbed seats and backs and have been painted day-glo colors). They were intended to be used (I asked the guards) and were surprisingly comfortable, which meant that I spent a leisurely time getting to know the work. It was such a good idea that it made the conventional, seat-less art exhibition seem dumb. I can’t be the only visitor who’s more relaxed and takes more time over something when I’m sitting down. Imagine reading a novel standing.

You might think that looking at paintings seated would create problems with the viewing position, but that’s such a matter of personal taste anyway. It was said that Bill Lieberman (curator at MoMA and then the Met) used to sit in a wheelchair as he hung shows which was just the effect of Heilmann’s wheeled chairs. I’m almost six feet tall but tend to hang things low (at least 2″ lower than was standard when I last had a standard to work with), and only one of Heilman’s paintings was hung conspicuously low: Tomorrow’s Parties (1979-94), a diptych approximately 4 x 5 ½ feet that centered around my belly-button (in the installation shot below). The artist was involved in the hanging throughout, which I suspected because of the close groupings of works that a curator would never consider. The guard I talked with (himself a sculptor) said Heilmann attempted to create conversations among the paintings. By offering us a seat she allowed us in on the conversation.

Heilmann is always spoken of as a painter’s painter, and I suspect that’s because her paintings reveal so much of her thinking and efforts: her starts and stops and her revisions. They are full of pentimenti (the term art historians use for visible evidence of change, which literally means repentances); these have the effect in a work such as Hokusai (2004) of animating the painting. The small colorful rectangles set on a white ground appear to wobble a bit due to slight auras that are remnants of their minor adjustments of size and placement.

Installation view; third from left is The End of the All Night Movie, and to its right is Tomorrow’s Parties.

Viewing the paintings at a conversational pace also allowed me to appreciate the subtlety of works such as The End of the All Night Movie (1978) (in the installation view above). There’s a thin, black vertical stripe to the right of the pink rectangle that’s distinguished from the black ground by its gloss, which changes with the incident light. And below the pink rectangle two tiny pink specs and a longer dribble have escaped – the dribble reveals the trajectory of the paint.

Part of the exhibition installed on the ground floor. In the foreground is a bench inlaid with tiles, then a table with ceramic plates. The paintings on the walls are grouped in clusters.

The exhibition actually offered quite a range of viewing experiences since in addition to occupying the second floor galleries, another group of paintings and ceramic pieces were installed on the ground floor behind the café (above), which meant that you approach them from a distance and if you sit to eat (some of the café chairs are by Frans West and they also have colorful webbing) you see them through glass and at a middle distance. It’s truly the rare exhibition that is willing to join you at lunch.

The New Museum is also showing Live Forever: Elizabeth Peyton (through January 11), and apparently I’m not the only one who noticed that the museum staff who greet you and sell tickets all look as though they just stepped out of Peyton’s work. Not only are they all young and beautiful, but they have the same casual, slender (slightly undernourished artists?) look of Peyton’s friends and the various celebrities she repeatedly paints. It was an amusing touch.