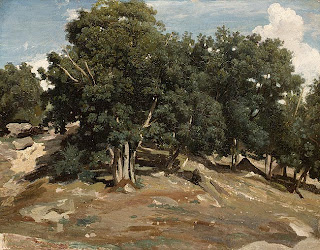

Camile Corot Fontainebleau: Oak Trees at Bas-Bréau, 1832 or 1833

Oil on paper laid down on wood; 15 5/8 x 19 1/2 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Studying Nature: Oil Sketches from the Thaw Collection at the Morgan Library

Oil sketches present a particularly intimate view of the artist’s working process. Usually defined as works created out of doors and directly in front of the subject (although views out a studio window may qualify), the earliest date to the 17th century although the bulk of the genre dates from the late 18th- early 19th centuries. They can be considered paintings as they are executed in oils, but the fact that many are on paper (often mounted to canvas later to increase their sales value) means that they can be found in drawings collections as well. They are always small, as they had to be easily portable.

The Morgan Library is currently celebrating a recent gift with Studying Nature: Oil Sketches from the Thaw Collection, an intimate exhibition of twenty works, as befits its subject. Eugene V. and Clare Thaw began as collectors of old master drawings, assembling a spectacular collection which they have been donating to The Morgan Library through the years (more than 80 of which are exhibited in another gallery) and recently gave 135 oil sketches jointly to the Morgan and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

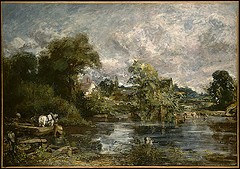

As works made for the artists’ private use rather than for sale many oil sketches were unsigned and collectors’ and scholarly interest in the genre, which only dates from the 1970s, has devoted a lot of effort to identifying the artists. The exhibition includes well-know artists such as Corot and Constable as well as a range of lesser or barely-known French, British, German, Belgian, Scandinavian, and Italian painters. The renown of the artist has little effect on the appeal of the sketch.

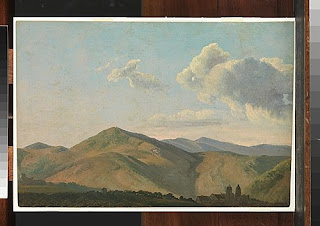

Simon Denis (Belgian, 1755–1813) Mountain Landscape at Vicovaro, oil on paper, 8 5/8 x 12 7/8 in., The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On Saturday The Morgan held a symposium on New Research on Oil Sketches, which I attended in the helpful company of my friend, Daisy Craddock, a painting conservator and a landscape painter who does sketch outdoors (albeit in pastel). The opening talk was by Charlotte Gere, an independent scholar who with her husband John, Keeper of Drawings at the British Museum, assembled a collection of oil sketches beginning in the 1950s which they later donated to the National Gallery, London. She described a time when these little paintings were so ignored that they were still within range of scholars and curators, making the entire audience jealous with recollections of purchases for five pounds Sterling.

Winslow Homer Artists Sketching in the White Mountains (1868) oil on panel, 9 1/2 x 15 7/8 in., Portland Museum of Art, ME. Homer shows artists at portable easels, under umbrellas to baffle the light. A backpack for carrying the equipment is in the foreground.

Ann Hoenigswald, conservator at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, spoke about the paint-handling that sketches involved, which because of time constraints and the necessity to work with wet paint consisted of a sort of short-hand for recording effects of the landscape. She described artists not only adding but also removing paint with their fingers, rags, sponges and both the hair and butt ends of their brushes. She also showed pictures of artist’s work boxes and easels designed for out-doors work; one advertisement bragged that an artist using its contraption could paint while running after animals! Her images included a number of wicked caricatures of painters working out of doors, chasing after sketches as they blew away and huddling en mass in front of a view.

Artist Emil Kosa Painting (1941) photograph by Peter Stackpole. The kit for outdoor painting didn’t change much from the 19th to the 20th century.

John Gage, noted scholar of color, recounted artists’ frustration with their materials in front of nature as well as the difficulties pleine air painting posed from the weather and banditti; Corot mentioned a pistol as part of his equipment. Gage mentioned the irony that while greens were the color most common in nature, they were the least available from paint manufacturers so artists had to resort to mixing greens before the practice of color-mixing was standard. Richard Rand, curator at the Clark Art Institute gave a provocative talk on the oil sketches that Claude Lorraine was said (by contemporaries) to have produced, although Claude’s drawings of artists working in nature always showed them as draughtsmen (see below). While two possible examples survive, the inventory from his estate mentions 137 small works and optimistic members of the audience might be on the lookout for the trove. If Claude actually worked out-doors in oils, said Rand, he would have been at the head of the European tradition.

Claude Lorraine An Artist Sketching (ca. 1635) ink, 32.1 x 21.4 cm, The British Museum.

The afternoon closed with Courtauld Institute Professor John House’s ruminations on Impressionist paintings and whether they conformed to the earlier traditions of oil sketching. While small, portable and produced out of doors they were conceptually similar to finished paintings done in the studio. The earlier tradition of oil sketches, by House’s reckoning, rejected the conventions of landscape painting of the time, being anti-picturesque and avoiding the most obvious views of monuments and famous sites. Instead they favored novelty and a sense of discovery which would only have been appreciated by other artists or by connoisseurs very familiar with the subject.

Under the Eaves at The Morgan Library: The Thaw Conservation Center

Treatment area of the Thaw Conservation Center at The Morgan Library, supported by the collectors who donated the oil sketches.

Cherrywood cabinetry at the Thaw Conservation Center, The Morgan Library.

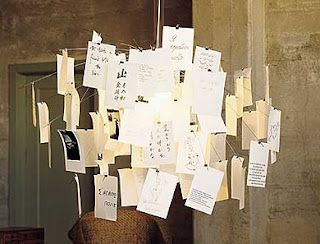

Daisy and I had a treat at lunch when Peggy Ellis, Director of the Thaw Conservation Center at The Morgan showed us the splendid facilities specifically designed to include areas for teaching and encourage curators, librarians, scholars and others to learn more about the materials and care of works on paper. The center was designed by Sam Anderson who also planned handsome conservation labs at MoMA and the Harvard University Art Museums. The cabinetry throughout is of the most beautiful cherry-wood, lending the space the feel of a library more than a laboratory. And there are subtle, humorous touches: an Ingo Maurer lamp with pendant pieces of paper greets the visitor and the receptionist’s desk is behind a screen of the sort used in paper-making.

Ingo Maurer’s Zettel’z 5 lamp hangs at the Thaw Center’s entrance, a whimsical touch for a paper conservation laboratory.