I’ll admit it up front: I like small exhibitions. I’ve seen too many monographic shows in major museums where an artist looks less interesting after an entire career is lined up than when represented by one work at a time. Besides, I’d rather spend half an hour with 20 carefully-chosen works than an hour and a half with the 350-400 works in too many exhibitions (that being my maximum uninterrupted time-span, and rather more than most visitors, I’d suspect). So I’m happy to call attention to two small exhibitions in D.C. of fewer than a baker’s dozen pieces each, both of which will reward the serious visitor.

Radical Light Fixtures; Moholy-Nagy and Co. at the National Gallery of Art

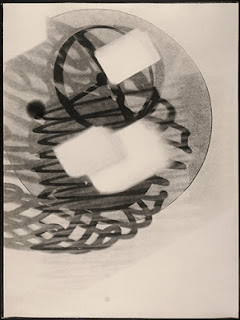

Laszlo Moholy Nagy photogram (positive) 1922-24, National Gallery of Art; the exhibition also includes a photogram from which this was made (e.g. a negative to this image’s positive). The sense of movement from the spring and the blurred white objects in front of it imply movement, which Moholy incorporated into at least one of his sculptures, Light Prop (1930)(a reconstruction of which is owned by the Harvard University Art Museums). Moholy used the moving sculpture which casts changing shadows as the subject of the film Light Play: Black, White, Gray (1930).

A fascinating small exhibit, Radical Light Fixtures; Moholy-Nagy and Co., is tucked into the 2nd floor galleries of the National Gallery of Art’s East Building through some time in March, 2009. Drawn entirely from the collection, it consists of nine works from the 1920s in varied media by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and work by four artists to whose ideas he responded: El Lissitszky’s cover for Wendingen, a lithograph by Malevich, a Jean Puni relief and a painting on panel by Rodchenko. The exhibition follows Moholy’s musings on the cubist structure behind Russian modernism merged with his interest in light as a dematerializing force. It also traces the speed at which ideas traveled from Paris to Moscow to Berlin in the 1920s, not to mention ideas Moholy brought from Budapest and Vienna.

Jean Puni Suprematist Relief-Sculpture (1920s reconstruction of 1915 original), painted wood, metal and cardboard mounted on wood, 20 x 15 ½ x 3 in., the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA’s relief is more or less contemporaneous to that owned by the National Gallery of Art and currently on view.

According to curator Harry Cooper’s gallery notes, Moholy was proud that he redirected the metal workshops at the Berlin Bauhaus from making samovars and jewelry to making light fixtures. Cooper selected the Moholy pieces (a photograph, a photogram and related photograph, 2 collages, 2 linocuts, one lithograph and one painting) because in various ways they explore light. The photogram, of course, is an index of actual light reaching un-blocked areas of photo-sensitive paper. The lithograph plays with light and shadow around a geometric structure while the collage includes a tubular element corresponding to the shape of a modern fluorescent light bulb.

All of this got me thinking about modernist lighting fixtures. The most well-known Bauhaus lamp is Carl Jacob Jucker and Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s table lamp, modern in styling but utterly conventional in conception. If the school produced more adventurous designs, I don’t know them. There are two significant examples of lighting from the 1920s-30s, however, that are thoroughly modern in their use of exposed tubular bulbs: one by Eileen Grey, the other by Gerrit Rietveld. Interesting that two architects thought about light bulbs as structural elements.

Eileen Grey, floor lamp (1930s), 36″, chrome and incandescent tube. I have never actually seen one of these lamps although it (or a copy) is still in production.

Gerrit Rietveld, hanging lamp (1920) 41″ x 15 3/4″ x 15 3/4″, glass-enclosed cords, wood, tubular bulbs; MoMA owns an example which is usually on display.

Golden Seams; The Japanese Art of Mending Ceramics at the Freer Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Nineteenth-century raku tea bowl with kintsugi repair. Freer Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

I’d been looking forward to the Golden Seams exhibition (at the Freer through May 10, 2009) because of a long-standing interest in art conservation and the philosophical judgements involved in so many restoration decisions. I don’t mean the decisions about how to preserve or repair an artwork but the inherent question of what is being preserved: the idea of the work as represented by its original appearance, or the physical remains which incorporate its history and use? Nothing highlights the judgement involved as well as the Japanese method of repairing ceramics known as kintsugi (golden joinery). Kintsugi involves the use of laquer to reattach broken ceramics (stoneware or porcelain), which is then coated with silver or gold. Not only is there no attempt to hide the damage, but the repair is literally illuminated.

Raku tea bowl with golden repair (source unknown).

Kintsugi has a history: the Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1434-90) sent a damaged celadon tea bowl back to China where it was repaired according to custom: held together with visible pieces of metal which resemble staples. In response his craftsmen developed kintsugi. These golden repairs are especially associated with utensils used in the tea ceremony which are intentionally simple and rustic, usually of stoneware; this acceptance of the accidental is consistent with Zen Buddhism which was behind the culture of tea. The Japanese have used kintsugi on their own ceramics as well as those from China and Korea. It is said that some bowls have been purposely broken so that golden repairs can be made, increasing their value.

The Freer exhibition includes comparative examples of Sung/Yuan ware repaired according to the Chinese and Japanese methods as well as a piece repaired with gold that has been elaborately patterned so it looks like brocade fabric. The small gallery contains 13 pieces and is situated off a larger gallery featuring the use of gold in Japanese art. You can find further examples of golden joinery in the Freer’s Korean gallery, not all labeled as such.