Rijksmuseum Amsterdam with banner for For the Love of God Damian Hirst, November – December, 2008

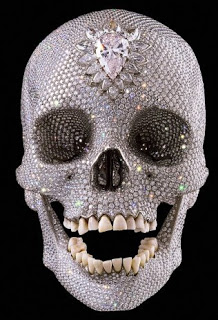

I arrived in Amsterdam on Dec. 14 on an overnight flight, took a nap and awoke to the suggestion from my friend, Barbara that we go to the Rijksmuseum for the last day of an exhibition. The work in question was For the Love of God, Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull along with a small room of paintings that Hirst selected from the museum’s collection. We had the singular experience of waiting in a long line that snaked through rooms filled with work by Rembrandt, Vermeer, Van Goyen and their peers which the crowd ignored in anticipation of seeing a platinum cast of a skull with real teeth (from a 35 year old man who had lived around 1800, we were told; he could have used some cosmetic dentistry) set with 8,601 diamonds.

The only information the museum provided was the number of diamonds, the source of the skull, the fact that the artist’s mother provided the title – For the Love of God – when her son told her he planned to set housands of diamonds onto a skull, and the modest art historical comment that “like Hirst, 17th-century artists often referred to death in paintings as moral exhortations to viewers … sometimes quite literally, others referring less directly to the transience of life. The skull was shown in a darkened room by itself with theatrical lighting (which I’d guess was done by outsiders; it’s not the sort of effect that museum lighting designers employ). The adjacent room with Hirst’s selection of paintings included a sentence or two by the artist explaining his choices. It’s always interesting to see an artist’s response to earlier work and Hirst clearly picked through the store-rooms, selecting modest but interesting paintings that are overlooked, if indeed they’ve ever been on view: among them were three still lifes with trophies of the hunt by Jan Weenix, a scene of Pan and Syrinx by Cesar Van Everdingen and a bald Heraclites by Ter Brugghen.

Installation detail of Andy Warhol’s exhibition Raid the Icebox 1 (1970) at the RISD Museum.

I’ve long had an interest in museum exhibitions selected by artists. The earliest I’m aware of was at the RISD museum in 1970 when Andy Warhol was invited into the collections storage and produced Raid the Icebox 1 with Andy Warhol. (documented with a catolog). Warhol emphasized the museum function of acquisition rather than that of display, showing the entire shoe collection in its storage cabinet, a group of sculptures arranged as they had been in the store room and a stack of paintings leaning front to back against a wall.

Installation detail of Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992), Maryland Historical Society

The National Gallery, London began a series of artist-curated exhibitions, The Artist’s Eye, in 1981 with a group of works that David Hockney selected from the Gallery’s collection and it did much to show how an artist interacts with art of the past. Hockney included a screen that is normally in his studio, with postcards pinned to it – pointing out that he learned from reproductions as well as from the paintings themselves. MoMA began a similar series of exhibitions titled Artist’s Choice in 1989. Scott Burden was given access to the collections and chose to exhibit a group of Brancusi bases without their accompanying sculptures, emphasizing that what one artist takes from another may be something marginal rather than central to the earlier artist.

Isabella’s Subtext(s) in the Veronese Room, part of Artist, Curator, Collector; James McNeill Whistler, Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner. Three locations in the creative process. A Centennial Project by Joseph Kosuth (2003), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Then there are artists for whom the re-arrangement of a museum’s collection is the material of their art, such as Fred Wilson, who has revealed the unexamined social history behind museum objects, or Joseph Kossuth, who has incorporated museum collections and literary quotations into collages of cross-century dialogues.

If the Rijksmuseum was serious about presenting its collection through the eyes of living artists, surely it would have started with a Dutch artist for whom its collection functions as a primary source, not a foreigner whose interest in the (universal) subject of death corresponds to a small part of the collection. Beyond whatever I might think of Damian Hirst or his appeal to the public’s interest in spectacle, the Rijksmuseum’s display of his work came off as a particularly crude pandering to public interest and income producer. It’s not what one expects of a great museum.