Albrecht Durer, Wolf Traut, Hans Springinklee and Albrecht Altdorfer after Jorg Kolderer, The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I (1515, Bartsch edition, 1799), woodcut (42 woodcuts and 2 etchings; original edition printed from 192 blocks), 357 x 295 cm, National Gallery of Art (shown installed at the Gallery). This is one of three monumental scenes celebrating the emperor which took 14 years to produce. It stands more than 11 feet tall and is the first work seen in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s glorious exhibition, Grand Scale, Monumental Prints in the Age of Durer and Titian.

Printing is at least as old as written history: Mesopotamian cylinder seals were impressed in clay and ancient signet rings were pressed into wax in place of signatures. But printmaking as we usually think of it was dependent upon the development of paper which, in Europe, dates to the 15th century (although textiles may have been printed before then). It’s worth remembering that until the end of the 19th century when photography replaced it, printmaking of one sort or another was the means by which visual images were widely disseminated. Prints illustrated books of all sorts, reproduced portraits, views, celebrations and battles and functioned as devotional images for those who could not afford paintings; they served as pattern-books for craftsmen of all sorts, handbills, news illustrations and book-plates. And prints were crucial for artists; Rembrandt never traveled to Italy and while he knew some Italian art from paintings which passed through the Amsterdam market he mostly learned from reproductive engravings.

The size of prints was limited by the size of the required press and the size of the paper available. For the uses mentioned above these posed no problems. But at some point in the 16th century a lesser-know tradition developed of monumental prints created from multiple sheets of paper assembled into images intended for public viewing; the precedent for such multiple-sheet images may well be printed maps. Monumental prints substituted for paintings, murals or tapestries or served as wall-paper. Because of their size and uses few of them have survived; many are unique examples and some of those are incomplete.

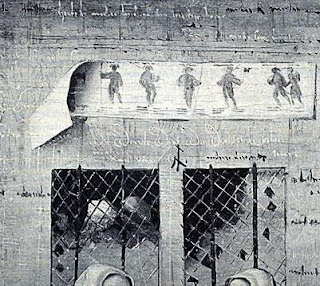

Detail of Tavern Scene (above), showing print of soldiers peeling off the graffiti-covered wall above the windows.

The exhibition Grand Scale, Monumental Prints in the Age of Durer and Titian, which makes its final stop at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through April 26, 2009 is the first ever devoted to the range of monumental Renaissance prints and it is a stunner. It was organized by the Davis Museum and Cultural Center at Wellesley College and was curatrd by Larry Silver, Farquhar Professor of Art History at the University of Pennsylvania and Elizabeth Wykoff, Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Davis. Among the 47 works are woodcuts, engravings and even a few etchings from northern and southern Europe; there are maps, topographic scenes, an astronomical chart, reproductions of religious and secular paintings and one example of modular-repeat wallpaper. They include the precedent of Mantegna’s Battle of the Sea Gods, four spectacular prints after Titian (including the cinematic Submersion of Pharoh’s Army in the Red Sea), stunning chiaroscuro woodcuts after Becafumi, Durer’s work for Maximilian, scenes of Turkey and India, and several erotic entertainments by Sebald Beham (who is usually known as one of the Little Masters for his tiny prints the size of large postage stamps). Beham’s Fountain of Youth (c. 1531) depicts nude, co-ed bathing and assorted hanky-panky in a scene most appropriate for the walls of a tavern, or more likely a bordello.

A conservator at the National Gallery of Art assembling their impression of The Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I which was donated by David P. and Elizabeth S. Tunick in 1991.

Unquestionably the star of the exhibition is the Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I, one of a suite of three monumental prints which A. Hyatt Mayor described as Maximilian’s program of paper grandeur. Despite its size (more than 11 feet tall), this bombastic piece of political propaganda was in such demand that the blocks survived and were printed for centuries; the one on view, from the National Gallery of Art, was printed in 1799. It is much too large to hang in the exhibition galleries so was located on the way, in the large hall between the coatroom and the auditorium where curator Shelley Langdale has wittily hung it with several contemporary monumental prints. An excellent article on the history of the Triumphal Arch and monumental prints generally as well as the work required to assemble the National Gallery’s Arch is available on-line here.

This exhibition is not to be missed by anyone interested in Renaissance art or history, prints, or visual communication. These prints are rarely on view (the only one I know is Maximilian’s Arch which stands outside the British Museum’s print rooms) and never together. While you may know them from reproductions it’s hard to imagine their impact. This exhibition is truly a fresh look at a significant chapter of art history and confirms the fact that for some ideas bigger is better.

Frans Huys Lute-Maker’s Shop, mid 16th century, engraving. A print by Sebald Beham of peasants dancing is used as decoration above the shop’s fireplace; that’s one print that certainly didn’t survive! The exhibition includes a Beham scene, Large Village Kermis, with dancing peasants.