Post by K-Fai Steele

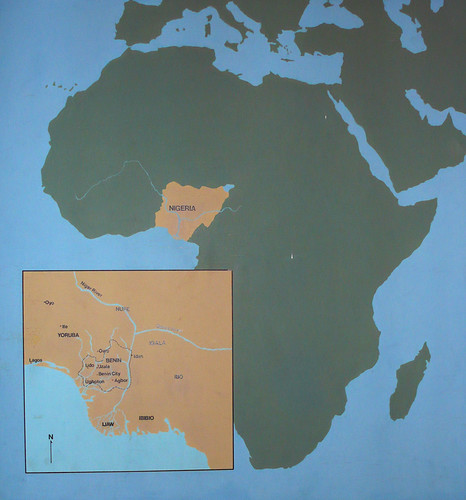

Map of modern-day Nigeria, showing the location of Benin and Benin City

I went to go see IYARE! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theater at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology a week ago, an exhibit that deals with the historical roots of the Benin culture today by looking at its golden period in the past. Close to 100 objects from Penn’s collection of Benin artifacts are on display.

The Benin, or Edo Empire stretched from 1440-1897. Iyare! – May you go and return safely! is shouted by onlookers as Edo nobles head for Benin’s palace.

The Kingdom of Benin is something I knew little about, except that it’s now in present-day Nigeria, and has nothing to do with the modern Republic of Benin. It is also famous for its bronzes which were seized by the British in the late 1800s causing an Elgin Marbles-esque controversy.

At times I feel awkward gawking at the different collections throughout the Penn Museum, perhaps because I feel like I’m participating in cultural tourism, a result of my generation’s polite guilt when it comes to potentially misunderstanding another culture.

A 19th century Edo copper alloy head with a carved elephant tusk from the Penn Museum’s Africa section. This normally would be part of an Ancestral Shrine. The tusk is carved with graduated adzes then worked with knives to achieve detail. Photography in the IYARE! Exhibit was not permitted.

You hear the sounds of the IYARE! show before you see it (drums and horns and crowds from a video) as you approach through the Alaskan peoples exhibition. The first thing you notice as you walk in are the colors of the exhibition. Red drapery hangs behind some objects, and the walls are painted a color similar to dry adobe bricks. Red symbolizes power in the culture, influenced by blood and of the carnelian, coral, and jasper beads worn during ceremonies. The objects, depicting mostly warriors, nobles, the monarch’s mother, and holy animals, are made of copper alloy and are the color of bronze sculpture.

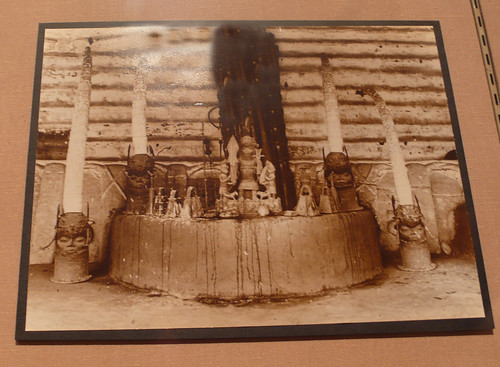

Photo of an Ancestral Shrine from the Penn Museum’s Africa section.

In the center of the room is a reproduction of an ancestral shrine, symmetrically flanked by two huge carved elephant tusks atop copper alloy bases in the forms of heads. The Benin Kingdom’s monarch was the Ọba, a king who ruled over the population above a set of titled chiefs. (Today, Edo people still profess loyalty to the current Ọba Erediauwa. Each year he and three hundred chiefs reenact historical conflicts and stories, mostly in front of these shrines (they literally are backed by their ancestors). Also on the shrine are brass bells and small copper alloy sculptures of warriors and nobles.

A ceremonial sword from the Natural History Museum in New York. In the ceremony of the Ugie Erhọba, each important chief comes and twirls this object, called an ẹbẹn.

The Royal Court of the Edo people is the only sub-Saharan state whose art shows 500 years of continuous palace life, mostly in copper alloy figures and objects and hundreds of brass plaques. The plaques were seized during the British Punitive Expedition of 1897, a military strike that led to the British annexation of Benin Kingdom. Afterwards the British Admiralty auctioned them off in Pairs to defray the costs of the Expedition.

Photo by Steven Tatum. They’re called The Benin Bronzes, but they are actually brass (“brass” suggests cheapness to Westerners). Image from the British Museum in London. They depict the Ọba, chiefs, courtiers, and foreign allies (like the Portuguese, who arrived in the 1460s). A specific guild of men made these brasses because historically it was thought that women were too impure to be handling the highly ritualized materials (metals).

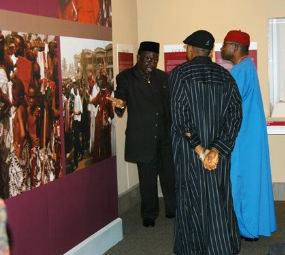

The goal of the show at the Penn Museum, it seems, is to give you an as-complete-as-possible view of the history of Benin City, and to show how Benin Palace life is still reflected in contemporary Nigerian culture. This was done successfully by guest curator Dr. Kathy Curnow, Associate Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University. According to the IYARE! informational website which augments the show, the opening included “cultural dancers” and the breaking of the kola nut (a tradition used for a variety of events, but principally to welcome guests to a village or house) by guest of honor Chief Eduwu Ekhator Ọbasogie, the Ọbasogie (who I believe is one of the positions of nobility under the Ọba) of Benin Kingdom. The show even has a blog.

Visitors at the IYARE! opening. “US-based Nigerians from Benin and elsewhere” in traditional dress. Photo from the IYARE! website.

I found a statistic that only 8,557 visitors went to the National Museum of Benin in 2000. Perhaps the objects are so common to the average Bini citizen that no one would pay to see them? Do the objects cease to have meaning to their own people once they’re taken out of their original element and set on display? Or perhaps it’s because most visitors to museum in Nigeria are tourists, and Nigeria’s political climate has been wracked by corrupt politics over the past ten years. The particular location of ancient Benin City has been one of the most active centers of human trafficking and prostitution in Africa (see article).

Photo of Penn Museum’s director Richard Hodges in traditional American dress at the IYARE! Preview. Photo from the IYARE! website.

The inclusion of the video made in the late 90s, which was the origin of the crowd noise, singing, and horns that greeted me before I entered, is excellent – it injects life and utility into the objects behind plexiglass. Even editing seemed influenced by Benin culture–the idiosyncratic wipes, the dancing type with different titles for each segment on a red background. The most important thing is that a cultural and social context is provided for these objects. Seeing this type of supporting text and information is worth a visit in itself, as I’ve seen plenty of shows at the PMA and MoMA which have entirely omitted descriptions and cultural meanings. The show helped to alleviate my guilty cultural tourism by giving me what felt like a thorough academic image of Benin Palace life.

IYARE! Splendor + Tension in Benin’s Palace Theater at the Penn Museum closes on March 1, 2009.

—K-Fai Steele is a Philadelphia artist who last wrote for us about the Beijing fire that destroyed part of Rem Koohaas’ CCTV towers.