At a moment when black power has new meaning, and bell bottoms and lava lamps have had a resurgence, artist Barkley Hendricks came to Penn, sporting dark glasses layered atop a blue beret. His late afternoon talk yesterday comes in advance of the fall opening of his Birth of Cool exhibit at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (it just closed at the Studio Museum in Harlem and will stop in Santa Monica on its way to Philadelphia).

“The city and I have a love-hate relationship. My 2-years younger brother was murdered here,” began the Philadelphia native, who lives and teaches in New London at Connecticut College.

A bit of a charmer, Hendricks is a funny mix of ego and diffidence, discussing his work in terms of its technical challenges and methods–info for students sandwiched between anecdotes about each piece.

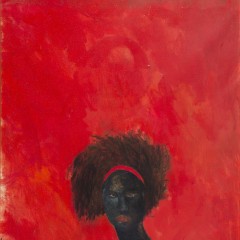

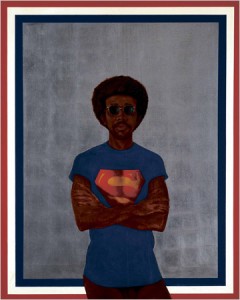

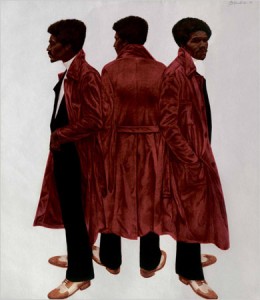

But it’s not the anecdotes or materials that make this work of particular interest. It’s the beautifully painted content–dark-skinned subjects, reflecting their time and their individuality, yet standing timeless and universal–a sort of African American hagiography, iconic against flat fields of color. Hendricks himself, in one of his few art historical references in the talk, mentioned Byzantine icons. He tipped his hat to Picasso in a couple of paintings, including Blood, a red-on-red portrait (his red period?) of a young man whose stance and plaid clothes call to mind the Picasso’s acrobats in harlequin.

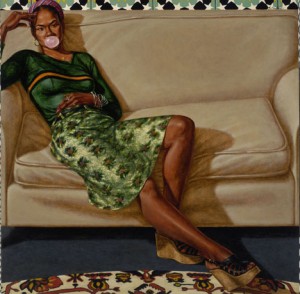

I particularly liked the information he gave about his choices–choosing a tile pattern for a background in Sweet Thang, adding balloons to “Arriving Soon” (the painting sat incomplete in his studio for a couple of years until the balloons appeared–in the studio and then in the painting), or omitting the word “nihilism” from a subject’s t-shirt. I also like how he told about the sitter in Sweet Thang first pouring out her heart to him until he was moved to tears. “Then she blew that bubble.”

Hendricks, by the way, is a PAFA Certificate holder, where he was one of Louis Sloan’s students; he also has a Yale BFA and MFA,where he studied under Walker Evans.

Hendricks came of age in the ’60s, and that era’s desire for Black empowerment and visibility is reflected in his work. His 1969 painting Icon for My Man Superman has as its subtitle a quote from Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale–“Superman never saved any black people.” Hendricks, who said he grew up loving comics, recalled that there were no black people in there–but “if there were, they were always blue. They never got the color right.”

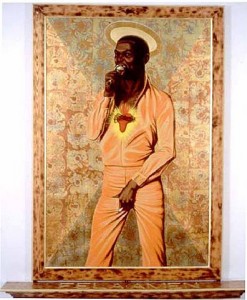

Hendricks is a political painter. His portrait of Nigerian singer Fela Kuti turns him into a saint and icon. Hendricks said the Nigerian government tried to kill the singer. The singer’s mother, died under suspicious circumstances, pushed out of a second-story window. In the frame of the painting is embedded a camera to spy on the gallery. Soon to be installed in the exhibit in Santa Monica, he said he is hoping the camera will be properly hooked up there to stream live video.

But the political content is also subtle. And this is where things get quite interesting.

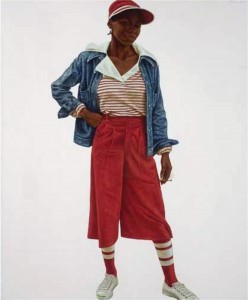

Hendricks’ Byzantine icons are also full-length fashion plates standing against blank photo backdrops. (He has a photography interest and many of his portraits are based on photos, even photos of strangers on the street; he also paints from life).

I am struck by how there’s a conversation that goes on with my old Jimi Hendrix black light poster (it’s not the one that’s all over the internet, but a two-tone purple and green portrait, with the planes of Hendrix’s face running into the background). Hendricks-the-artist plays with white clothing bleeding into white backdrops or black into black backdrops. The clothing-encased body is often flat, but then emerges with luscious dark skinned volume from the collar and cuffs.

He loves people, he loves how they present themselves–their clothes and their attitude. And in those choices of clothing and hairdo, he presents not just character, but also a cultural time capsule that is the figure en costume, each subject sartorially self-exoticized. These are black people not trying to be white people but just being themselves, and everyone’s a character.

I want to say that without Barkley Hendricks, there is no Kehinde Wiley, who also takes academic painting technique and history to express Pop culture. Wiley, like Hendricks, appropriates poses from religious saint paintings, creating often full-length portraits of his street hustlers in hip-hop regalia. Wiley’s settings also are flattened, although Wiley uses wallpaper patterning to domesticate his subjects, the fronds of pattern crossing over their outfits, making street dudes look positively tame and lovable–not to mention gorgeous.

Both artists take subjects with major attitude and humanize the threat their clothing and posture implies. They are inserting African Americans into an European art history with its pale faces and tastes. But Hendricks is about political power and about the individual personality in a way that Wiley is not.

To say Hendricks is political, however, oversimplifies. He’s about African American musicians, especially jazz musicians. He has a strong sense of connection to people. He showed a slide of a self-portrait in which he placed himself in Virginia, where his family has roots, and where he is called Doc and Ruby’s Oldest Boy, which is the name of the painting. Hendricks’ anecdotes include his ex-wife, his ex-girlfriend, his models, his friends. His personal life is part of what fuels his art, which is a mix of the personal and the impersonal, the private and the public. He uses song lyrics and titles–like (Marvin Gaye’s) What’s Going On– for his paintings and recently completed a print of jazz musician Dexter Gordon, who starred in the movie Round Midnight. He has embraced them all as his people.

There’s also a sense of humor here, a willingness to laugh at himself and to paint work that has the spark of the real world! A portrait of his wife is called Mon Petit Kumquat. She’s a 6-foot tall woman, heroic in platform shoes, delicately holding a kumquat between her index finger and her thumb.

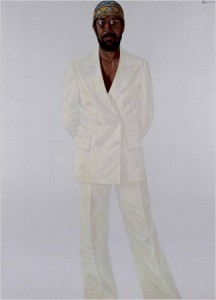

He is able to tell a joke on himself–laugh at some criticism he got from the late Hilton Kramer in the New York Times, who wrote, “Hendricks is brilliantly endowed, but has a tendency toward slickness.” The comment resonates in the titles of two of his paintings. One is a self portrait dressed in all white, “Slick.” The other is a nude self portrait, in athletic socks and a white cap. It is called Brilliantly Endowed. It didn’t come directly out of the Kramer comment, Hendricks suggested. “I took a shower and looked in the mirror. Hey, that’s a painting.” But he grabbed onto the joke, and the picture is richer for it.

It’s that touch that allows Hendricks to deal with touchy subjects and still charm. He knows how to get a lot of mileage out of indirection!