The impact of a great master on his followers is a fascinating topic. Rodin’s work loomed so imposingly over the next generation of sculptors that they all claimed to dis-own his influence (not entirely truthfully); many did so by returning to direct carving, since Rodin was a modeler whose carved work was executed by assistants. Cézanne’s followers showed no such anxiety of influence, as can be seen in Cézanne and Beyond at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (through May 17). The exhibition is truly spectacular in the quality of the works and the questions they provoke.

The curators have borrowed a large and sumptuous group of Cézannes and extraordinary artworks by Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Mondrian, Marsden Hartley, Leger, Arshile Gorky, Morandi, Jasper Johns, Brice Marden and others. One can argue with their choices, particularly with the youngest artists (Jeff Wall, Francis Alys, Luc Tuymans and Sherrie Levine), but not with Cézanne’s pervasive importance or the quality of the exhibited work. They cajoled loans from St. Petersberg, Stockholm, Paris and Berlin as well as American museums and numerous private collections. There’s one of the longest list of lenders I’ve ever seen. And it will repay multiple visits.

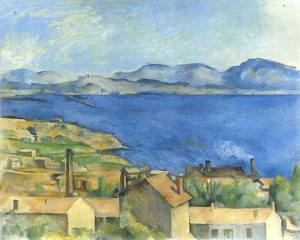

The hanging of Cézanne and Beyond, however, is open to question. I cringed when I began to see advertisements for the exhibition around Philadelphia: a dour Madame Cézanne in her armchair beside Picasso’s portrait of Eva also asleep in a red armchair, her head on her shoulder filled with erotic dreams, no doubt. I hoped that the marketing department had devised the campaign for what could be more conventional and less significant than Cézanne’s motifs and genres: portraits, landscapes, still lives, and an occasional foray into history painting in the form of the pastoral? Cézanne took the Impressionists’ inversion of the academic hierarchy of genres and ran with it.

The curators, Joe Rishel and Katherine Sachs, explained their choice to juxtapose similar genres throughout the exhibition as a way of de-emphasizing the depicted motifs and foregrounding the artistic means and language. To some extent it works; in a gallery hung with Cézanne’s apples, Arshile Gorky’s copy of Cézanne’s apples and apples by Charles Demuth and Ellsworth Kelly the viewer may be inclined to ignore Meyer Shapiro’s interpretation of Cézanne’s apples as sublimated sexual desire; or is psychological interpretation of art just out of fashion? But arriving at a gallery of paintings of skulls (Cézanne’s, Braque’s, Brice Marden’s, Gorky’s and Sherrie Levine’s copies of Cézanne’s) can we believe that death – the universal subject – is ever merely a pretext for painterly experimentation?

Besides, emulation is only one of the ways in which modern artists responded to one another. Leo Steinberg famously wrote of Cézanne’s work as the foil against which Picasso painted, making solid the spaces between objects in retort to his predecessor’s breaking down of forms and space into a uniformly-atomized whole. But there is no question that Cézanne’s art became the universal key to modernism, opening whichever doors his followers chose. With this in mind I went around the exhibition and thought of those doors and the places they led. These are a few of the entry ways I discovered in Cézanne and Beyond; viewers will certainly find their own:

– Cézanne and a varied language of paint (see particularly Cézanne’s The Bather, c. 1885, with its drips, scumbles, and varied brushwork and the work of Jasper Johns)

– Cézanne and the malleability of space (Cézanne’s skewed tabletops which return in Picasso and in Matisse’s Bowl of Apples, where the fruit bowl resembles a hat in one of Matisse’s Fauve portraits)

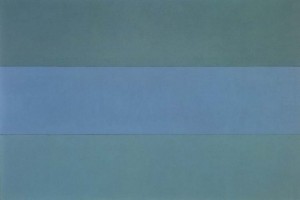

-Cézanne and negative space (enter Ellsworth Kelly in watercolor and oils)

-Cézanne’s insistent pattern of brushstrokes and the emphasis on planarity (Clement Greenberg has already covered this topic)

-Cézanne and the unhinged outline (pursued not only by Beckmann and Mondrian but by Matisse in his Portrait of Olga Merson)

-Cézanne and bad painting (as in Marcia Tucker’s 1978 Bad Painting exhibition; see Portrait of Olga Merson again, as well as works by Beckmann and later artists)

-Cézanne and the palette knife (the exhibition doesn’t include any of Cézanne’s pallette knife paintings but does include fairly unusual examples by Picasso and Matisse, and I wonder whether there weren’t implications for Giacommetti’s sculpture as well)

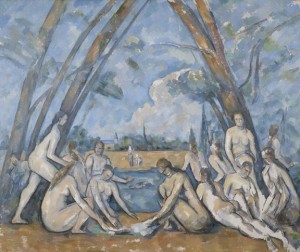

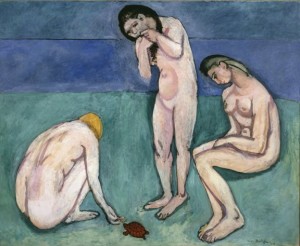

– Cézanne and the place of the human figure within abstraction

-Cézanne and the aesthetic of the unfinished ( a subject without conclusion)