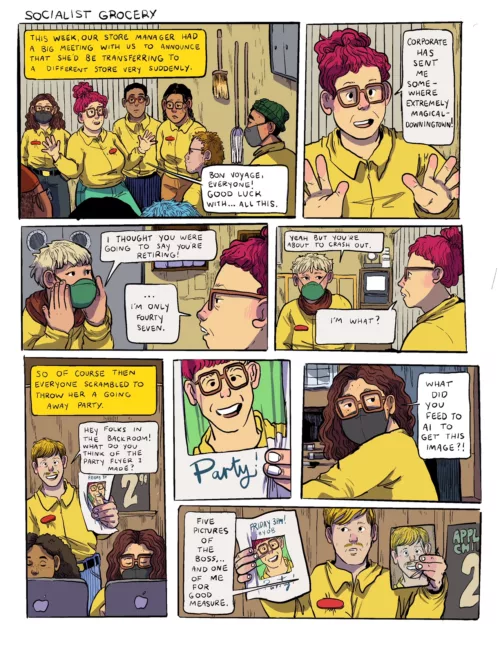

A fascinating exhibition, Chagall and Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater, 1919-1949 just closed at the Jewish Museum, N.Y.C. but fortunately moves on to the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco (April 25-September 7, 2009; the exhibition catalog is distributed by Yale University Press). It tells the little-known story of the two Jewish theater companies in Moscow that received state sponsorship under the young Soviet government.

Habima performed in Hebrew as a conscious reference to biblical history, although the language was unfamiliar to most Russian Jews. The Moscow State Yiddish Theater (GOSET) presented contemporary dramas and modern versions of traditional Yiddish dramas.

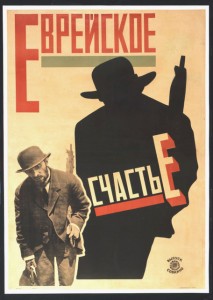

The exhibition situates both companies at the intersection of Soviet post-revolutionary politics, pro-ethnic but anti-religious policies, Zionism, ethnographic interest in folk tales from the shtetls, Constructivist and Expressionist art and Russian avant garde theater, and finally of Stalin’s ruthless destruction of all artistic freedom and experimentation. The costume and stage designs, set models, posters, theater murals and photographic and film records of actual productions convey an art that was both experimental and accessible.

While Chagall is in the exhibition title, for name recognition I would guess, the more daring set and costume designs were by others: Nathan Altman, Ignaty Nivinsky, Isaac Rabinovich. No credit is given for the extraordinary make-up effects in a number of productions which appear to derive from German Expressionist paintings, making the actors look like carved wooden puppets – the more so since GOSET’s productions favored stylized, anti-realistic body movements.

The exhibition made me realize how little I know about 20th century design for theater, by artists or theater designers. Only a few examples regularly appear in the art history literature, most of them for dance productions: costume designs by Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova and Oscar Schlemmer, Picabia’s set for Satie’s Relâche, Matisse’s and Picasso’s designs for Diaghilev, Noguchi’s sets and costumes for Martha Graham, Rauschenberg’s and Warhol’s costumes and sets for Merce Cunningham.

By the 1960s American experimental dance was often performed in art venues and visual artists created happenings and performances which erased distinctions between art, performance and life. The expansion of visual art into installations, environments and interior design, the use of large and sculptural forms by puppeteers, and the collaboration of artists with some adventurous opera productions are just a few of the reasons that the history of experimental theater design might be of current interest. This superbly-researched and realized exhibition provokes a broad range of questions and fills in one small part of that history.