Part 1 of this post can be found here

Chandigarh was a project taken on by Le Corbusier in 1951, after the original architects Matthew Nowicki and Albert Mayer (of Mayer, Whittlesey & Glass of New York) ended the project following Nowicki’s death in a plane crash. The city was planned as the new capital of Punjab, following Partition in 1947 (when India was divided by the British into India and Pakistan – Hindu and Muslim). It was a city for the generations to come – a very optimistic 1950s industry-fueled venture as stated by India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharal Nehru, “an expression of the nation’s faith in the future”. This new capital of a bloody state (Partition resulted in about 500,000 deaths in Punjab alone) was to be “a place where arithmetic and geometry would replace the oxen, cows and goats driven by peasants.” It was planned to be different from other cities like the crowded, dusty Delhi we had been in days before. It was an experiment in whether or not organization and cleanliness could make for happier Indian citizens.

City Museum, Chandigarh.

The City Museum in Chandigarh documents the city’s planning through newspaper articles, photographs, and architectural drawings. It’s housed in an impressive, Le Corbusier-ian complex that’s solid, imposing, concrete, and reminiscent of municipal buildings from the 1970s in the US. There’s a small creek that runs inside the complex with rags and other detritus in it where we spotted a good number of wild marijuana plants.

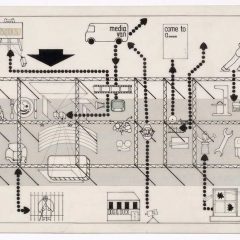

Chandigarh City Layout, City Museum.

Each sector is divide by very wide boulevards which open onto rotaries, and never seem to have gridlocked traffic in them. The red lights have 100-second countdowns on them, and scrolling messages that read messages like “turning off your motor at a light will save you fuel and money” and “educate your child.” The streets and restaurants are clean – smoking has been banned there, as well as plastic bags. Sculptures of people are forbidden there, “the city is planned to breathe the new sublimated spirit of art” as stated in the Edict of Chandigarh, a manifesto for the city.

Public sculpture, Chandigarh.

Another public sculpture

Le Corbusier planned for the city layout of Chandigarh to correlate to the human body, with the Capital Complex (government buildings) at the northernmost part, the City Center, with pedestrian-only piazza at the heart, the Leisure Valley and Gardens at the “lungs” of the city, cultural and educational institutions at the “limbs”, and “7 different types of roads, ranging from pedestrian to high-speed traffic as “arteries” and “veins”.

Everything in the city seems to have been touched by Le Corbusier, from his Capital Complex masterpiece, to the 3-story residential houses, to the tapestries in the High Court and the manhole covers (a casted map of the city). A notable place in the city not designed by Le Corbusier is the Fantasy Rock Garden. Built on an old dumping ground for urban and industrial waste, it is a seemingly endless paradisical maze made entirely of recycled materials including electrical sockets, broken plates, rebar and concrete. It compliments the city well because of the nostalgia it evokes- the deliberate romanticism you get from the crumbling aesthetic.

Fantasy Rock Garden, Chandigarh.

Fantasy Rock Garden, Chandigarh.

Interior of Post Office (abandoned floor)

One problem that we read about in modern Chandigarh was the poverty, and the segment of the population referred to as “jhuggis”. They’re squatters who create homes and communities out of found materials, for lack of a better word they are slumdwellers. A newspaper article in the City Museum read, “their self-sufficiency and inventiveness is outside the law and the insanitary and haphazzard conditions are in stark contrast to the planned character of the city as well as detrimental to their own well-being.” We saw the jhuggis around the city occasionally- very dirty children, they looked like characters out of a Dickens novel who’d beg and tug at our clothes. The city has tried several methods to stop the spread of these jhuggi slums. One way was low-cost housing, another was in situ resettlement, where the city would mark out plinth areas, allowing jhuggis restricted space to create their own homes. Both methods so far have failed, leaving these people in incredibly dense slums where necessities such as clean water, sewer systems, and electricity are grossly inadequate.

A massive jhuggi settlement we saw from a bus by the

outskirts of the city. The smell coming out of it was

awful (sewage, garbage).