I spent a Friday in late March at Rutgers/Camden listening to painters wonder whether painting was dead or transformed, and what it meant for them as artists and teachers.

The symposium, To be or not to be, went on for two days, but I was there to moderate only day one of what was a passionate discussion. I also took the opportunity to look at the two exhibits associated with the symposium–one at the Stedman Art Gallery at Rutgers, and one at Hopkins House in Haddonfield. They will go on to April 25.

The symposium, the brain child of Rutgers faculty member Margery Amdur, and the exhibitions, curated by Amdur and Hopkins House Curator Bruce Gerrity, grew out of Amdur’s personal concerns, as a painter who materials include cut mylar and resin as well as a faculty member who teaches students who seem to have concerns that differ from her own.

What I heard and what I saw at the symposium and galleries set my mind working.

Among those speaking during the two day symposium were some local people, including installation artist Amy S. Kauffman, traditional painter Scott Noel, stained glass phenom Judith Schaechter and University of Delaware Assistant Professor Lance Winn, who is coordinator of the MFA program there. I loved the willingness of this conference and exhibition to tackle the range of what can be included as paintings–sculpture, video, drawings, photos, prints, cut paper, lenticular moving images, comics, collage, whatever.

I didn’t hear Schaechter or Noel, both of whom were scheduled for Saturday, but I did hear Kauffman, who presented a wonderful film about her art practice, and Winn, who wonders just where we stand on earth–expressed through works that explore language and terrain and the position of the body.

Some of the symposium speakers I heard were focused on the art historical record and the continuity of the human desire to make art. But there was a lively discussion on the day I was there about whether there had also been a sea change in what the young were making and whether it was a challenge to the art historical record. Panels on day one epresenting the youthie view were Winn, Kauffman, graffiti and trash memorializer Steve Pauley and Brooklyn artist Liz Brown.

All this set me thinking about just what it is that makes art of today different than art of 50 years ago. And it certainly is different–and not. Ah, creativity; there is always room for change.

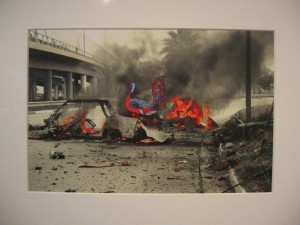

The generations that grew up with grinning family snaps at the Grand Canyon, Sesame Street, Super Mario Brothers, MYST, graffiti and Scarface have incorporated all those experiences into what they are making. Their current world includes YouTube and multiple photos transformed through Photoshop, stored–for now–on line only to vaporize some day, constant computer input, and if you’re looking for what’s real in the lives of urban artists crowding into cities to work together and live together, it’s sidewalks–gray, graffitied, littered with trash and signage. It’s 9/11 seared into the television screen so frequently that the after-image remains there, a permanent scar casting a cloud over our viewing pleasure.

That’s what kids have seen the most of. So paintings of nature seem quaint and kitsch. Instead, we get paintings of paintings of nature and paintings of illustrations of nature with crystals and Rainbow Brite! Nature is where we go camping for a different experience; it is not where we live.

If you’re just looking at art history, you’re not looking at today’s visual reality–which includes images galore of Britney Spears and Brangela, Tron and King of the Hill, WWE SmackDown and surfing the big wave on WII. It’s not that nature observed by previous painters is irrelevant. But it’s got a lot to compete with.

The two shows associated with the symposium ran the gamut. I did pick out some of the younger artists as younger–Brown (she’s got a sharp sense of humor about the images of advertising, cinema, and promotion that litter the landscape) and Winn. But I would not have picked out Pauley’s somber graffiti- and trash-based works as youthful. They are somber memorials, carved in granite and made into rubbings. And I assumed from her dreamy, eco floating worlds that Pam Langobardi was younger than she was. The students at the symposium were deeply interested in what she had to say.

There was plenty of other stuff there that was great to look at, and not just from the youthie contingent. From the meticulous Carol Prusa were strange LED embellished, obsessive drawings on smooth plaster domes. From Dennis Farber, who teaches at MICA, came a crusty, materials-influenced painting of a mountain (a self-portrait?). I also enjoyed work by Elin O’Hara Slavick and Suzanne Slavick (they are sisters) , Patricia Bellan-Gillen, and also eco floating worlds from Pam Longobardi that the students in the audience really related to.

Vis a vis local connections–Kauffman and Rebecca Saylor Sack for starters. Since the Symposium was organized by Amdur, who shows at Projects Gallery, there were several provocative pieces by some other Projects Gallery artists–Henry Bermudez, Frank Hyder, and Caleb Weintraub–all of whom challenge a definition of painting as just pigment on canvas. And from Rodger LaPelle Galleries, a number of moody paintings by former Philly-ite Matt Bollinger, painting blurry video frames with odd compositions of threatening scenarios. What’s happening here, as in painting in general, is not exactly clear.