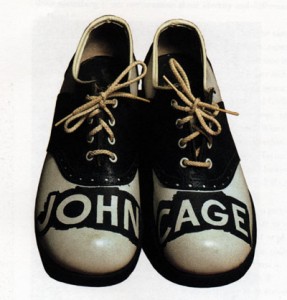

I think it was the 13th of August, 1992, that artist and neighbor Ray Johnson called me with the news that John Cage was dead. I know it was early in the morning, and not the day he died, the 12th, because when I went outside to get a coffee and a New York Times, Cage’s obit was fully formed, a solid page, a gray tombstone reserved only for those who have come to New York to change the world. Ray hung up and I assume spent the day dialing all sorts of people to tell them that John Cage was dead, without really saying what or who Cage was to him. The two met around 1948 at the famed avant-garde Black Mountain College. When Johnson died in 1995, the world discovered in that artist’s home the white and black shoes he’d painted with Cage’s name on them across the toes.

John Cage has been the silent bandleader of contemporary art for decades, according to Robert Storr, dean of the Yale University School of Art, who outlined the bulk and body of contemporary art in the West in a 90-minute breakneck lecture at the American University of Paris last week.

Storr, the decidedly unslick 2007 curator of the Venice Biennale, argued convincingly that Cage has had more to do with American (and international) art than pretty much anyone since Duchamp. Cage (1912–1992) spent decades using random chance operations to mine the world for noise and turn it into music (his 1952 4’33” silent piece in three movements the most well-known). The musician set traps for sound (and life) to experience the everyday and the mundane. His “prepared piano” placed objects on piano strings to alter their sounds. Working with chance and randomness engendered a contemporary aesthetic focusing on the varied flavors of “nothing,” one that continues to permeate every pore of the art world skin.

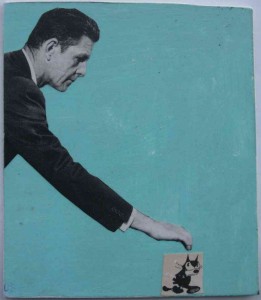

Storr’s thesis danced though dozens of artists, including Gerhard Richter, Ellsworth Kelly, Philip Guston, Nam June Paik, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, George Maciunas and Christian Marclay who either directly or indirectly sampled Cage’s magic. That magic flirted with the potent precept: There is no reason for anything, hence the embrace of chance. [Johnson would be more interested in synchronicity – an excellent word to look up – but he did his fair share of nothings as well]. Richter made abstract chance-driven Cage-ian paintings in dull grays (“colors nobody wants“) and old master-style pop images of toilet paper and color charts lifted from paint stores. More to the point, Kelly determined that he could make paintings “without ideas” and launched into collage in the early 1950s using torn colored papers to develop compositions. Johns could kidnap numbers or maps or flags are re-present them. Marclay more recently, said Storr, tied an electric guitar to an old truck, miked it, and drove through the sagebrush – an ode to country music. My favorite works of Marclay’s include the video “Telephone,” (1995) – featuring dozens of black and white Hollywood video clips of people answering a ringing phone. “Hello? Hello? Is anyone there?” echoed often without conclusion.

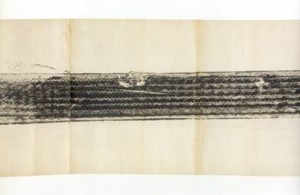

Another favorite is Rauschenberg’s “Automobile Tire Print” (1953) where Cage was “printer” and “press,” driving his Model A over 100 sheets of typewriter paper that Rauschenberg had laid out one rainy day on Fulton Street in NYC. The tire, inked with black house paint, produced a kind of musical score; the finished work resembles a scroll. [See Rauschenberg talk about the event.]

Cage’s influence also extended to video art (Nam June Paik), performance art/living sculpture (Gilbert & George), and dance (Merce Cunningham). Storr indicated that you can see the smiling ghost of Cage playing footsie and more with creation from New York to Kyoto. (Sonic Youth on their SYR4 album performed Cage’s piece Six and one of Four).

But it wasn’t always easy for the lanky Cage. Storr delighted in telling the story about our hero fresh from Chicago landing chez Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst in 1943. The heiress had arranged to transport the musician’s instruments for a concert in her gallery, the famed Art of This Century. Cage, an ambitious artist, arranged on his own to give a concert at the Museum of Modern Art, and in telling this to Guggenheim, discovered how twisty and tangled the art world could be. She canceled his show and refused payment for the transport of his instruments. Cage broke down and cried. In the next room, Duchamp, “the uber-art father figure,” was idly rocking in a chair, smoking a cigar. He wanted to know why Cage was crying; Cage told him, and the Frenchman said barely anything but according to Cage, in Marjorie Perloff’s John Cage: Composed in America, “…his presence was such that I felt calmer…He had calmness in the face of disaster.”

Calmness, unlike the cool violence of Warhol and brutal brand of art making by Pollock, suggested Storr, seeped in everywhere; it was not media specific – say in painting or serial nihilism – but through Cage’s Zen-like principles. Teaching at Black Mountain and New School for Social Research in the 1950s, Cage’s lectures and ideas reached deep into a generation of artists so varied that now, said Storr, “We are living in a world where the conversation about art is about the conversation.” And it led Richter, for one, to paint about painting in the language of painting. “He determined that one image was as good as another.” But Cage, composer, writer, doer, thinker, participant and go-to guy in contemporary art had no agenda to speak of, and appeared to walk through post World War 2 art world with a smile on his face…changing everything in sight.

Storr’s lecture made for an eventful evening, as far as a discourse on silence and nothing went. For many, Storr’s lecture answered quite a few rumblings about the seeming pointlessness of contemporary art, but left open the question about whether the enormous stream of nothing(s) really came to something. My guess is yes: Coming back to Johnson’s portrait of John Cage, I think a bit about meeting the Buddah on the road and stepping into his shoes.

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer based in Paris. His next exhibition, Confessions, Obsessions & Indiscretions opens Saturday, May 9 at Soma Gallery, Cape May, New Jersey.