Kehinde Wiley doesn’t look much like the dewy hip-hop dudes he paints amid wallpaper patterns. He’s all shoulders, low to the ground, with a gentle, expressive face and a shyness in his demeanor that belies the power of his build. He came to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Wednesday to talk about his art.

He also talked a lot about power, sexualized figures, the homosexual gaze, hyper-sexualized young African-American men, and art historical sources.

Wiley’s art education, which included a BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and MFA from Yale, caused him culture shock–from romantic bohemian at SFAI to hard-nosed and more conceptual at Yale. The MFA was followed by a significant transitional year as a resident artist at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

“I got a studio space to paint in and time to reassess all that was done to me in six years of art education,” he said. “So much of what I did [in art school] was to please my professors.”

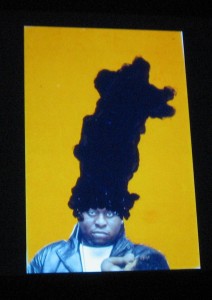

That year in Harlem, walking down the street, he saw a mug shot. “This was a unique, perverse kind of portraiture.” It made him think he wanted to celebrate individuals who looked like himself in the milieu of paintings, a powerful social tool for telegraphing information, he said.

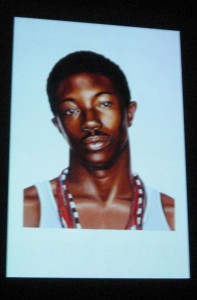

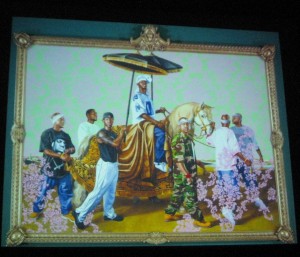

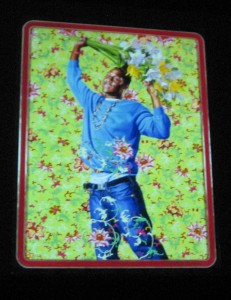

He began to approach people on the street with a sales spiel. “All of these models are complete strangers. I convince them to come back with me to my studio,” he said, then allowing them (much of the time) to choose a pose to emulate from an art historical painting. He photographs them, usually in their street clothes, and then makes paintings from the photos.

But he also sometimes insists that they emulate poses not of their choosing. In one example he showed, the young man balked because the Dutch idea of a fine figure of a man was not at all masculine by today’s standards. It’s that slippage between cultural expectations and gestures’changed meanings out of their time and place context that Wiley is trying to capture.

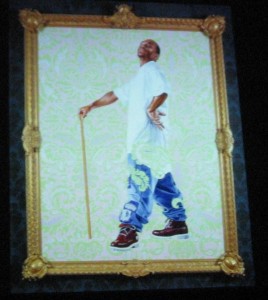

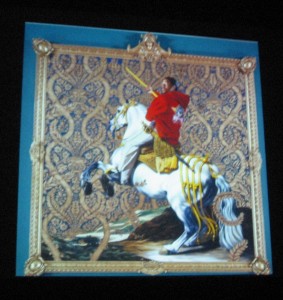

“Painting occupies a specific place in what it means to be culturally dominant,” he said, discussing conventions of power–the central white male figure on his land, the war hero on a horse, showing man’s dominion over nature.” Other sources he discussed are use of light to represent God in Hudson River School and Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings.

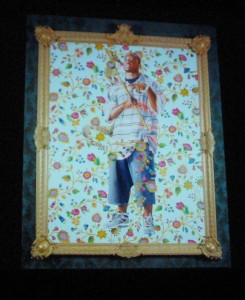

“One of my favorite artists, Kerry James Marshall, says you have to be very careful about the edge of the skin and how it meets the light in paintings.” Wiley then veered into a discussion of light on the skin of rapturous Christ figures and how such paintings were luxury goods for wealthy consumers. “They have blinged out frames that anounce themselves. Bling is nothing new–the desire to communicate wealth; and fear, the desire to shield yourself with material goods.”

Wiley has tried a number of other different sources besides Western paintings to shake up contextual clues. For a while he mined Social Realism for his source material. Using Mao-era poses, facial expression and background, Wiley has found another way to recontextualize young African-American.

In his World Stage paintings, Wiley inserts ordinary people into poses from heroic public art sources. “I was using models from Brooklyn and poses from Beijing.”

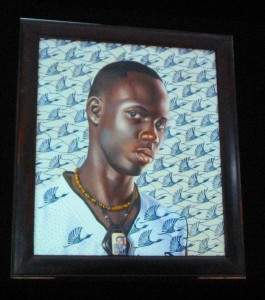

What brought Wiley to his paintings of African men was his search for his father, who had left the U.S. after his parents divorced. After not having any contact for 20 years, Wiley went to find his father in Nigeria, and discovered a man who not only looks like him but who makes portraits.

The African experience affected his methods for painting black skin, switching to indigo and purple underpainting.”So many preconceptions I had about portrait-making in Africa had to go out the window.” It had to do with the similarity of clothing and imagery and background, and how to get at the cultural slippage between ordinary Africans and their own culture’s heroic imagery, and how to make them not look American. Among the African sources he looked to were portraits by photographer Seydou Keita. He also looked to public sculptures in Africa, often made of concrete and often not on pedestals.

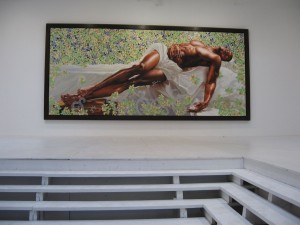

When he returned to Western art history, he went big–30 feet long, using images of fallen soldiers, Christ, and women, whose eroticized figures he translated into young African American men. The work, he said is “very much about a specific, demonized, eroticized demographic counterposed to specific imagery.” (We saw a show of this work at Deitch in the fall and wrote about it; this photo is from that visit).

In the brief Q&A after the talk someone asked what his subjects say when they see the final product, but Wiley said the responses run the gamut, from “How dare you, to Thank you, to What does it cost.”

Someone wanted to know about his use of Photoshop. “With Photoshop, everything is conceivable,” he said. He also uses projectors, computers, studio artists, “the whole nine yards to arrive at the images. …I do work with a team. I do paint the figure, but I can’t bear to do the decorative stuff.”

He also mentioned the “downside” of working on such big paintings. When you walk in the studio each day, you say to yourself, “Your not still working on that again!”