On Wednesday, Leslie Rogers called. A mad puppeteer, among other things, also sells her labor-power to Painted Bride. She was promoting an African-Indian dance troupe the coming weekend. At that point, it was still uncertain: “we’re having a hell of a time worrying if these guys will get here or not.” Painted Bride was in communication with senators and congresspeople, because visa officials on both sides had balked at twelve black men leaving their insular displaced community in Gujarat for JFK Airport. The troupe call themselves Sidi Goma, and are devout Muslims. Thanks to a supportive network of promoters and ethnomusicologists, they toured several years ago, and were now hoping to share their Sufi traditions with global audiences again.

The literature on Sufism will inform you only generally about the obscure Sidis; theirs is community of just 15,000 that detached from its East African origins eight hundred years ago. Like the whirling dervishes (also Sufis), their ritual performance is not just for the audience’s sake: its acrobatics and aerobics are intended to elevate the dancers towards the divine. The program at Painted Bride included a panel discussion in the lobby an hour prior to curtains, with a UPenn ethnomusicologist, the Bride music curator, and – most vocal – the tour manager Katrina Pavlakis, who’s apparently working pro-bono. She also had the most relevant knowledge: we wouldn’t see fire-dancing that night, she told us, as some elements of the ritual don’t leave their village. And is the Sidi community self-sufficient (read: isolated)? She answered, impatient at the idealizing inherent in the question: “well, yeah, if that’s what you call subsistence. Because of discrimination, access to education, and the size of their community, few are employed in the [formal] economy.”

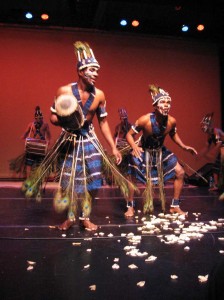

I didn’t absorb ethnographic specifics, but I left appreciating that we are about to see performed in a theater what’s usually done in a shrine. Seated, waiting, and reading the program, three pairs of words popped out from its first sentence: JOYFUL & EXUBERANT / (devotional) MUSIC AND DANCE / (from the) HIDDEN & MYSTERIOUS community.” Lisa Nelson-Haynes, one of the venue’s directors, emerged and amped the crowd with all the warmth and unselfconsciousness of a Baptist church. “Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve got a big and beautiful audience tonight…” is how she prefaced her request that we squeeze to fit the sold-out house. The lights dimmed, and before leaving stage, she added: “We lost one on the way – visa issues – so we’ve got 11 and not 12.” Leslie’s fear had been confirmed, and, it was a nasty reminder of things as they are and things as they should be. The show, however, wouldn’t suffer.

For their final number, the Sidi Goma did the inevitable: they gestured for the audience to join them. After the first brave few came forth from the front, it was barely sixty seconds before the stage filled. My appreciation for the evening only grew when I discovered how hard it was to move my body to their exotic, syncopated timing. (Afterwards, others concurred.)

The flood of strangers onto stage made me consider that the Painted Bride must be a special place. I didn’t know its history; I had only categorized it as establishment by its generous space in Old City, and the major acts it hosts. I also met no fewer than four people there involved either in philanthropy or publicity. Strange when I read the info sheet: it was founded in 1969 by six PAFA grads “hungry to present non-mainstream visual art” where there was none. It’s certainly joined the establishment, but Lisa Nelson-Haynes, when she introduced the show, stressed that the Bride “marks itself by promoting access to the artists” – through meet-the-artist receptions and pre-show talks (in philanthropy parlance, they call it a “member engagement”). This, after all, is precisely why I love Philadelphia over tier-one art market cities: artists are more accessible; fewer pretensions come between the art and the community of appreciators.

Just minutes following their bow, Sidi Goma joined us in the lobby for grilled vegetables and brownies; several of us gathered around the dancer with the best English. Someone asked what, in their villages, were their livelihoods? He pointed to his compatriots – M____ has juice stand; O____ has small area for farming; D___ does, how do you say, BUSI – goes around to the houses, giving blessings, playing malinga.” As we’d learned earlier, they are a subsistence people. The troupe, I imagine, are among the few Sidis that have traveled outside their country.

So come to the Painted Bride next season, their 40th. Artists on the fringe tend to dismiss big-bill cultural performances at theaters that sell subscriptions and draw their share of bourgeois empty nesters. But we must remember: we are so so lucky to be able to see performers from far-off places. (Next season, e.g.: a 6-member tabla ensemble.) Western culture wrecks much as it spreads, but not decisively. The positive potential in global information flows, jet travel, and consciousness is that, from the comfort of our city, we get to experience [ok, watch] religious ritual of a subsistence people as if we were in their village – a privilege recently unimaginable.

That most outgoing Sidi dancer – I asked for his take, briefly, generally, on this dialectic of cultural globalization. Here is what he said: “It’s good when people have tradition in their community – when they keep this thing – this instrument, or this song – going. But when they say – ‘my family HAD this thing, and we don’t know it now’ – that’s not good.”

Music and video (ugh, video) of Sidi Goma here