Recent art history that describes the 1970s as entirely Minimalist leaves out a lot; the same can be said for the predominantly U.S.-centric view. The Swiss Institute is showing the first solo exhibition of Manon’s, a survey from the 1970s to recent work (through June 30), and it’s an eye-opener.

In 1974 she placed the entire contents of her maximalist and erotically-charged bedroom on display as The Salmon-Colored Boudoir; a satin and fur-covered bed at its center was surrounded by mirrors and every square centimeter of the room was covered with objects to indulge touch, taste, smell, sight, and that most erogenous organ, the mind; among the stuff which crowds the space are Colette’s novels, plastic lingams, seashells displayed vertically to emphasize their distinctly vaginal apertures, jewelry and clothing strewn about, a left-over plate of oyster shells, pictures of people she admires, …. In turning her domestic environment into art and offering it to public view she created herself as the artist, Manon. Her private space was charged with sensuality, fetishism and memories of both fictional and historic women. Manon’s subsequent work as performance artist and as protean subject before the camera mined similar territory.

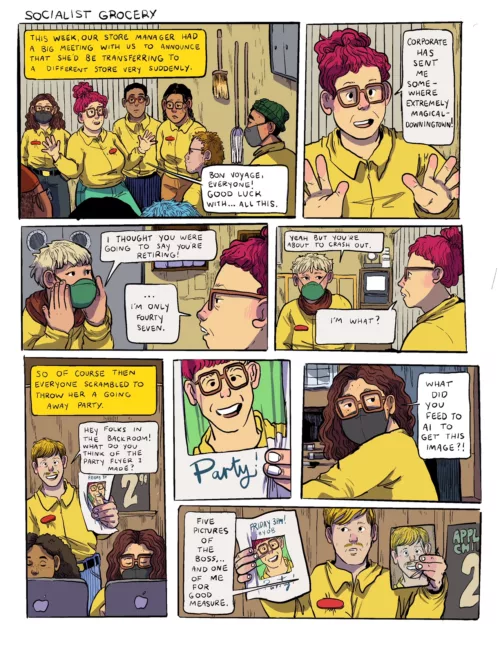

The exhibition begins with a recreation of The Salmon-Colored Boudoir then a selection of thirty-some black and white photos (part of a larger group) from The Grey Wall or 36 Sleepless Nights (1979). We see Manon as the vamp, the innocent, as a nude boy or a young man in jacket and tie. With no more than makeup, changes of costume and an actor’s ability to project character, the artist presents a self with ever changing identity. The series overlaps with Cindy Sherman’s slightly later exploration of constructed female identity, but with a distinctly bisexual edge.

The most recent work, She Was Once Miss Rimini (2003) is a slide show of the possible middle-aged incarnations of a woman who was once a provincial beauty queen: glamorous actress with a lap dog, yoga student in meditation, straight-jacketed mental patient, frumpy middle-class housewife, stripper with hands clutching nude, enhanced breasts. All are played by Manon and shot in the featureless space of her studio. This conceit may underline the artifice behind the work but its exploration of une femme d’un certain age who had traded on beauty in her youth has an obvious personal truth for the artist and for women in general that gives the charade its depth and poignance.

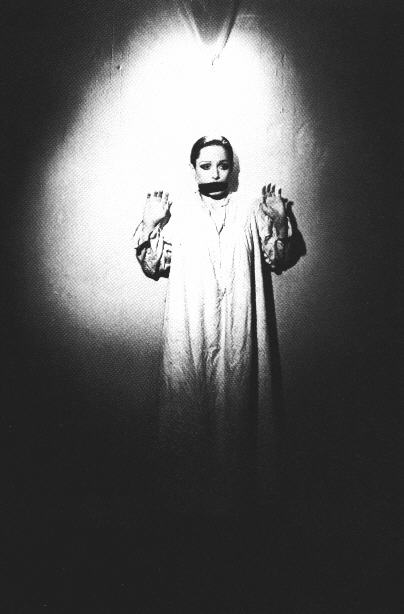

The Drawing Center has another U.S. debut: Unica Zürn; Dark Spring emphasizes the drawings of the German artist who worked in Berlin and Paris, although it includes several of her paintings as well. Originally a writer, Zürn turned to drawing and painting during the 1950s-70s, influenced by the automatic drawing of the Surrealists with whom she was associated. It’s hard to avoid the biographical with Zürn, who was the companion of Hans Bellmer (he of the nude, life-sized and dismembered dolls) and turned to art during a period of recurring mental illness that ended with her suicide.

While all the work is minutely-detailed and fantastical, it ranges in quality. Some drawings resemble the doodles of an adolescent, but her small paintings in opaque watercolor on board and the finest of the ink drawings exhibit a remarkably-controlled technique, more virtuosic than obsessive, and a truly fascinating and fecund imagination. They are peopled with imaginary, composite beings of only partially recognizable form (some are marine-like, others resemble mythical beasts) and created with detailed, rhythmic pen-strokes and often subtle overlays of slightly differing polychrome inks (or more fully colored paints). They recall some of the minute calligraphy of Paul Klee as well as the biomorphic abstraction of Kandinsky’s Munich period.

Zürn’s work is much too sophisticated to be characterized as a symptom of her illness; it is as fine as that of any of her Surrealist contemporaries and should be known more widely.

I previously reviewed a monograph on Marilyn Minter, whose work can be seen concurrently at the gallery Salon94 Freemans and at a MTV’s billboard-sized HD screen in Times Square as part of Creative Time’s series At 44 ½. Minter curated the Times Square video program CHEWING COLOR, which includes a short version of her video, Green Pink Caviar as well as Patty Chang’s Fan Dance and Kate Gilmore’s Star Bright, Star Might (through May 31, 2009).

Perhaps we’re now more willing to see Minter’s images of women derived from pornography for what they are: a provocation and critique rather than complicit tantallizing. The exhibition includes billboard-sized paintings of women’s mouths, and the video, Green Pink Caviar (playing in its entirety) which leaves us wondering at our varied reactions to the commercial and erotic implications of a woman’s mouth and tongue both savoring and spitting out viscous fluids. The video (which is for sale as a cd) is hypnotic and I’m terribly sorry not to have caught it in Times Square, although I can imagine it there. I wonder what a younger generation will make of it in a neighborhood now controlled by Disney; for those of us who remember Times Square as the center of Manhattan’s peep shows and adult movie theaters Minter’s in-your-face tongue activity is both captivating and repulsive. The video in its various locations becomes an exploration of private erotic pleasure versus public and commercialized sexual display.