Since the King of Pop died, I’ve been catching up on my Michael Jackson video watching. The ones that really grab me are Thriller and Beat It which aspire to be short movies and pretty much are. Jackon’s dancing is remarkable to watch of course. But his dance moves take on even greater visual energy and emotion when he’s backed up by a dance troupe mimicking him and amplifying the movements. It’s then that the quick-stepping, twitching, pirouetting and hip popping becomes one big satisfying wave of movement.

Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History by historian William H. McNeill talks about the physical and emotional underpinnings of dance and drill and other human synchronous movement. We all love to dance and we fall easily into step with each other when walking; even aerobics classes are satisfying whereas doing aerobics by yourself is odious. Why is that? McNeill says there’s something in the human bones and psyche that compels us to move together — and then rewards us for doing so. We feel good when moving together with others. There’s a spirit of group cohesion and shared emotion that happens, some pack animal body-and-mind-happiness that occurs.

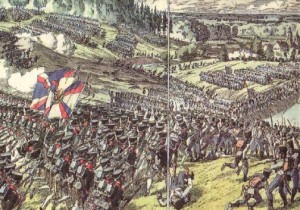

Our ancestors learned this, and dancing allowed them to bond. Dancing may even have helped foster language development (chanting being a natural partner with dance). Moving together rhythmically helped Homo Sapiens evolve and dominate the landscape over non-dancing and non-marching species. Governments have corraled group movement for use in the army — Hitler of course abused this human love of mass physical movement with his goose-stepping soldiers and Heil Hitlering citizens.

In very early times, organized religions allowed group dancing as a way to commune with god. (One of the byproducts of the rhythmic dancing for some people is the onset of a trance state, seen as a direct communication with god.) The Quakers and the Shakers got their names from the group movements associated with their religions according to McNeil.

Visual representations of dance, drill and other synchronous movement

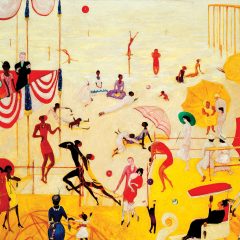

McNeill’s book got me thinking about visual representations of dance and drill and about visual repetition motifs in general. And here’s what I think: That even if you’re not physically moving but are observing dance or drill — or are looking at a visual representation in 2-D of dance or drill — the visual image triggers a similar pack-response as your eyes move around the image and pick up the the rhythmic movements and register them on you.

And while there’s less of a physical response when looking at a 2-D image than there is to looking at a video (after all, there’s no music to enhance the effects), there is still something immediately satisfying when you look at a work with a repeat motif of bodies moving together.

Popular culture and art both love these movement spectacles. Think of Busby Berkeley (watch video) and the Rockettes; the human wave at college football games; and the standing and singing of national anthems everywhere. Think the Olympic parade and church rituals (Catholic ritual when I grew up was all about standing sitting and kneeling en masse triggered by some unseen signal–all while chanting unknowable Latin words in haunting melodies). In choreographed dance for the stage, especially in musical theatre, often it’s the group numbers that bring the house down.

Certainly artists have always loved making images of synchronous bodies in motion. McNeill’s book has pictures of a Minoan Crete harvester vase from 1500 BC that shows people dancing and singing in time: Medievalists painted legions of angels (and legions of praying sinners) in synchronous harmony; Breughel painted peasants dancing at a wedding; and many artists working for governments have drawn, painted and photographed army battalions in formation.

In our day Matthew Barney, one of our age’s great visual image-makers, has a scene of a chorus of dancing girls ala Busby Berkeley in one of his Cremaster films.

Visual representations of repeat patterns

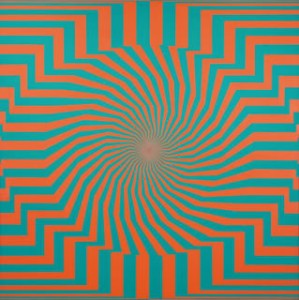

Mandalas and other abstract art designs with intricate repeat patterns have a similar bodily appeal. Mandalas are used for meditation and can produce calm or trance; Op Art is about provoking a bodily/retinal response of a different kind. Standing in front of a Bridget Riley painting triggers my flight response. (For more about Op Art check out this website.)

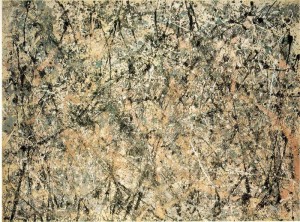

Jackson Pollock’s works are like melted mandalas.

One reason that works of abstract repeat patterns like those of Agnes Martin and Brice Marden are popular and have helped spawn an entire universe of artists working in similar fashion is that the works are satisfying to look at and make.

I’m not sure why all this fascinates but it seems that there’s a human need for perfection expressed in the desire to move together and make images of repetitive movements. We know we’re not perfect and maybe this is all a way of saying even though perfection is not possible we can get pretty close with these bodily and emotionally satisfying movements and representations.