I’m happy that I finally caught the current exhibition, Adventures in Modern Art: The Charles K. Williams II Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; assembled by a distinguished archaeologist with long ties to the Philadelphia area, the entire collection has been promised, with some works already donated to the museum. It makes a significant contribution to the PMA’s ability to tell the full story of American 20th-century art.

Th exhibition focuses on two areas: American modernists, particularly of the generation that showed with Alfred Stieglitz (it ignores the slightly later American Abstract Artists group) and American realists from Ashcan painters to the social realists and regionalists of the 1930s-40s, with a handful of European modernists whose work was significant to the Americans. It includes a few other works that caught the collector’s eye, such as a striking portrait by Georgio de Chirico and Louise Nevelson’s Rain Forest Column XXIV (1964) that is later than the rest of the collection. If most of the artists are members of the chorus rather than the soloists of American art history they still belong to the narrative, and while only one work is of large ambition, Thomas Hart Benton’s The Apple of Discord (1949), most of the artists are represented by work that shows them characteristically and well.

There’s too much work to address completely, so I’ll make comments about ideas and works that caught my attention. The first thing that struck me was how significant the watercolors were, whether by Charles Demuth, Emil Nolde, Morris Graves or George Grosz. Watercolors, by virtue of their storage needs, are usually handled by drawings rather than paintings departments (the exhibition was curated by Innis Howe Shoemaker, The Audrey and William H. Helfand Senior Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, who also produced a fully-illustrated catalog). They make it to the walls of museums too rarely and several artists in the collection, such as Demuth, Charles Prendergast and Joseph Stella did some of their best work in the medium.

The collection also gives a good idea of the revival and transmission of tempera painting in the 1930s, including artists well-known for adopting the medium, such as Paul Cadmus, George Tooker, Ben Shahn, and others such as Philip Guston who briefly adopted the technique before returning to oils. I researched the tempera revival some years ago and spoke with Paul Cadmus and Jacob Kainen, both now deceased. Kainen credited Kenneth Hayes Miller (represented in the PMA exhibition) who taught a form of tempera adapted from painting stage sets in his classes at the Art Students League; his students Reginald Marsh, Isabel Bishop and George Tooker are all represented in the exhibition with paintings in tempera. Cadmus confirmed Miller’s influence but said he learned his technique from Daniel V. Thompson’s Practice of Tempera Painting (1936) and from a colleague (Jared French, I suspect, whose work is also on view).

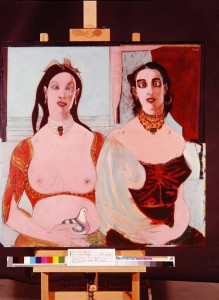

It was great to see one of John Graham’s bewitching cross-eyed women on a museum wall again (unfortunately the museum couldn’t provide a reproduction of it, so I’m showing one of MoMA’s Grahams). I’d recently been thinking about the artist; he’s fallen out of the cannon since MoMA put his paintings in storage. In the 1960s the museum regularly exhibited two Graham paintings of cross-eyed women (one a double portrait, see above) and an abstraction, so everyone passing through the museum knew of him. He was sui generis; the paintings of women in particular don’t fit easily into surveys of the period. But he was a charismatic figure who had a significant influence on other artists in New York in the 40s including Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, David Smith and Mark Rothko. Woman in a Tall Hat (c.1950) is a wonderful picture done in a technique that combines painting with drawing in the facial details; Graham used this unusual technique from the early forties, as de Kooning did in paintings such as Seated Woman (1940, PMA) and Queen of Hearts (1943-46, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden). I’m not sure whose idea it was.

There’s a small Man Ray painting, Female Nude (1923), that caught my eye because of its extraordinary technique: the paint was worked into herringbone patterns by closely-spaced palette-knife applications of wet-into-wet paint. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. And the frame is equally striking: a sculptural construction covered with paint that contains sand or some other gritty inclusion; I suspected it was made by the artist and museum staff confirmed my hunch.

A fine, almost Art Deco painting by Lyonel Feininger, Night Hawks (1921), is the sort of street scene of prostitutes that Kirchner was doing at the same time, although the Feininger is more rhythmic than angular and with a Cubist handling of space (the Kirchners were the subject of a recent exhibition at MoMA). Feininger is known for his landscapes and cityscapes, some of which are peopled with small figures but never focus on them to the exclusion of their surroundings, as in the Williams Collection painting.

George Ault’s somber, almost monochrome painting, The Machine (The Engine) (1922, see above) is striking, and a very early example of American interest in industrial equipment (I’m not counting the various bits of plumbing, etc. used by the likes of Morton Schamberg and Francis Picabia as stand-ins for people). In the same room is Joseph Stella’s silverpoint Portrait of Joe Gould; (c.1920); Stella evokes an aura of intensity and charisma with a simple profile portrait through the magic of his technique. Gould’s hair becomes a mysterious, floating form that reminds me of Toulouse-Lautrec’s prints of Loie Fuller’s diaphanous drapery (one of which can be seen here).

I expect that parts of the Williams collection will find their places on the museum’s walls once the exhibition is over, but it’s worth seeing in its entirety then waiting for the promised gifts.