Exhibitions devoted to a single work of 20th century art are extremely rare, and Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), on view through November 29, 2009 is exemplary.

Such focused exhibitions require two things: enough preparatory studies and works leading up to the magnum opus to create an interesting display and enough prior interest in the masterwork to attract an audience. Étant donnés: 1. La chute d’eau, 2. Le gaz d’éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas) (1946-66, designated ED in the rest of this article) passes on both counts. The PMA holds the bulk of Duchamp’s production and has been a proud as well as conscientious caretaker of his legacy; the Duchamp collection insures that Philadelphia is a pilgrimage site for students of 20th century art.

The exhibition will be of great interest to viewers who care about how an artist develops a work that is complex and challenging to execute; it is certainly required viewing for all Duchampians, as it contains a significant amount of unpublished photographic and written documentation and work. Duchamp spent twenty years on ED, working in secret, yet it incorporates imagery that dates to his very earliest sketches. The exhibition includes photographic documentation of ED taken by Duchamp as it progressed and posthumous photographs of the finished work in Duchamp’s second New York studio. Duchamp’s notes and studies for ED are assembled, as are various test studies for the nude figure and landscape, much prior work which anticipates all or part of ED’s subject matter and his manual of instructions for assembling the work at the PMA (which the museum published in facsimile in 1987, and has re-published, with English translation). It also includes a group of Duchamp’s Erotic Objects which were artifacts of the process of constructing the nude figure.

A small, separate section at the PMA exhibits work by a hand full of later artists who directly responded to ED (one could easily mount another exhibition on the subject) and two works by Maria Martins. The most provocative is Hanna Wilke’s film, Philly (1977) in which Wilke plays the part of the nude who takes control; she overturns Duchamp’s situation so that the viewer of his peep-show is toyed with by the nude.

Michael Taylor, the exhibition’s curator, pays the old jokester Duchamp the respect of taking him completely seriously. He researched ED for 10 years, talking with Duchamp’s surviving family, colleagues and friends from the period of ED, retracied the artist’s steps through the Swiss landscape that inspired ED’s background and read everything possible about it, published or not. The exhibition follows Duchamp’s laborious process of realizing a work that he had long imagined, his experiments with casting the nude figure and with creating a realistic-looking model after it (achieved with parchment stretched and dried over the plaster life cast, then colored and supported with an armature), designing and producing the landscape background and lighting the installation. Taylor’s lovingly-researched and clearly-written catalog tracks Duchamp’s process in much more detail than the exhibition and is required reading for anyone who wants to understand the full implications of the works on exhibit.

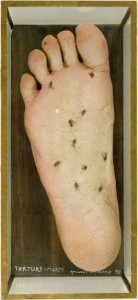

ED and its related Erotic Objects mark the only time that Duchamp was directly involved with the process of casting and he clearly relished its appropriateness to the subject of sex. Casting involves a series of interlocking positive and negative forms that perfectly match one another in obvious analogy to sexual congress. The Erotic Ojects, while anatomically undefined (until their origins were revealed by research), are clearly related to the body and function as sexual fetishes through the implication that their forms match bodily contours. They also fit in the hand and to hold or caress one is a vicarious sexual caress.

The superb, scholarly catalog includes Taylor’s account of ED’s genesis, construction, installation and legacy, all beautifully illustrated. It also includes translations of Duchamp’s correspondence with Maria Martins, the Brazilian sculptor whose sexuality inspired the artist. She was his lover when he began the work and was the model for the cast figure of ED’s nude; the correspondence reveals that Martins was his adviser throughout the process of creating the figure. The only thing Taylor neglects is a discussion of the peep shows Duchamp might have seen around Times Square (and perhaps in Paris), although he does discuss and illustrate precedents such as a 19th century pornographic stereoscopic image of a woman’s pudenda as well as higher-class porn such as Courbet’s The Origin of the World, which Duchamp likely saw when it was owned by Jacques Lacan. Three catalog articles by museum conservators are the first ever to analyze the materials and production of the Erotic Objects, the figure in ED and the evolution of the landscape in which she lies.

Duchamp’s work has generated an extraordinary amount of critical and academic attention, perhaps because it offers such an open field for interpretation and footnoted and cross-referenced research. Monographs already exist (in some cases more than one) on Fountain, the Large Glass and ED, not to mention endless articles, PhD dissertations and at least two journals devoted entirely to Duchamp. Taylor’s catalog is grounded in the physical reality of the work in ways that are rare in the scholarly writings. This combined with his extensive archival work will put some of the wilder interpretations of ED to rest. His attitude, however, is modest to the point of withdrawal. He will not give his own interpretation of ED, preferring to leave it open-ended and let other scholars build on his groundwork.

Taylor does concede that Duchamp, who early in his career rejected the purely optical basis of painting and sculpture, proposes in ED an erotic opticality. I see it somewhat differently, perhaps as a woman inevitably so. ED clearly grew from Duchamp’s sexual interests, combining furtiveness (the peepholes, referencing adolescent sexual initiation), enlightenment (the lamp of his mature sexual experience), the constancy of masculine desire (the eternally ejaculatory flow of the waterfall) and female receptiveness (he spoke of the nude as Our Lady of Desires to his lover, Martins). Yet whatever charge ED carries, for me at least, it is not a sexual one. While Duchamp played openly with cross-dressing, the objects of his sexual interest were always women; so it is surprising to find that the open crotch of his nude corresponds so poorly to actual female anatomy. I don’t buy Taylor’s suggestion that the distortion is an artifact of the casting process; Duchamp manipulated the parchment that he formed over the plaster cast of Martin’s body in various ways, adding hair and color as he wished. He could easily have reworked anatomical details at that stage. His results are strangely disturbing and sexually off-putting. I would suggest that with ED, Duchamp established a conceptual eroticism, in that any sexual response the viewer has to the work is not to what he sees but to the product of his own imagination.

On Sept. 11-12 the Philadelphia Museum of Art is holding a Symposium in conjunction with the exhibition, in memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt who, as a young curator, was responsible for installing Étant donnés. For further information call (215)235-7469.