The premise of Paint Made Flesh is that despite the dominance of abstraction, a number of European and American artists since the early 50s have depicted the human body as a way to explore both the pleasures and pains of humanity.

Organized by Mark Scala of the Frist Art Center, Nashville the exhibition is on view through September 13 at the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. before moving to the Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester.

It began with a bang: Picasso’s The Artist and His Model (1964); the 83 year old painter/self portrait regards the appealing flesh of his nude model knowing that his days of sexual conquest are over and he is left with only his brushes and erect thumb, visible through the hole of his palette, to express his desire. The label says oil on canvas but Picasso clearly used a very liquid, white enamel in places, the sort of industrial paint associated with Jackson Pollock’s dynamic skeins and splashes. One wonders whether this wasn’t a reference to a younger generation’s masculinity and erotics of paint.

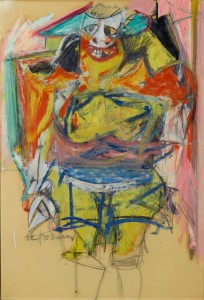

Beside the Picasso were two de Koonings in which paint and the bodies of women were clearly one, most spectacularly in the 1971 Woman in a Garden, where the woman’s body seems to melt along with the liquid paint.

The next two rooms were filled with a welcome selection of painters who worked in San Francisco and Chicago as well as better-known New Yorkers. It was good to see an early Diebenkorn along with paintings by David Park and Joan Brown; Brown’s Girl in Chair (1962) is a rare female nude painted by a woman, and the strength of her body was conveyed with the most massively troweled-on paint I’ve ever seen; the paintwork evoked the figure’s power rather than the surface of her flesh. Allbright’s late self-portrait reflected the artist’s intimate association of paint with flesh throughout his career (he was an extraordinarily appropriate choice to paint Dorian Grey’s aged portrait for the Hollywood movie of Wilde’s story).

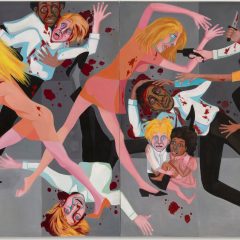

I rarely question the selection of works in an exhibition; that’s the curator’s job and it’s not up to me to propose the exhibition I would have done. However the selection in Paint Made Flesh, while providing an interesting survey for viewers who appreciate figuration, struck me as particularly arbitrary, especially the contemporary choices. It’s hard to understand the exclusion of Dubuffet, Giacommetti and Balthus among the generation of painters who lived through World War II, and the exhibition took no interest in a number of others for whom the depiction of the body had a particularly political aspect (Joan Semmel, Sylvia Sleigh, Robert Colescott , Barkley Hendricks).

Given the title I had expected the exhibition to focus on painters who depict the body with a significant emphasis on skin (such as Alice Neel or Lucian Freud, both included) and that was certainly one criterion; other painters such as Leon Golub and Maria Lassnig were selected because they emphasize embodiment, what we do to and with bodies and how our bodies are inseparable from our spirit as well as our social reception (but Marlene Dumas and Kehinde Wiley would also seem obvious choices along similar lines). For the life of me I can’t understand the inclusion of A.R. Penck’s stick figures or Susan Rothenberg’s body parts; while they deal with human narratives they do so without significant reference to our embodied-ness. If that level of mediated figuration satisfies the idea of paint made flesh, why not include artists such as Andy Warhol, May Stevens, Ida Applebrog or Jean-Michel Basquiat?

The exhibition was strong on two generations of painters working in London: the first School of London (Freud, Bacon, Auerbach and Kossoff but no Kitaj), and the younger Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville and Tony Bevan. Arnaldo Roche-Rabell was an interesting choice in the final section since his early work actually began with body rubbings which he then reworked. But it strikes me that Lisa Yuskavage and John Currin’s work is more about the expectations that viewers bring to paintings of nudes than about the bodies they depict and their inclusion takes the exhibition in an entirely different direction.

Paint Made Flesh assembled a group of works that made for compelling viewing but was problematic in relation its subject. Perhaps the provocation alone was sufficient.