Portraits are everywhere, right now, major portraits. I had a nice conversation with myself after seeing two terrific shows of Philadelphia portraits in the same week–the show Personal Views: Contemporary Photographic Portraiture in Philadelphia, at Gallery 339; and the paintings in Barkley L. Hendricks’ Birth of the Blues at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

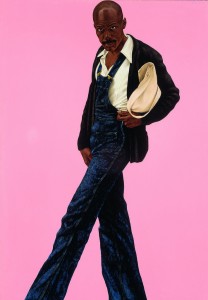

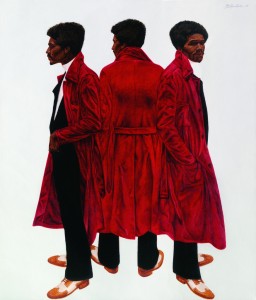

I was struck by, how in a funny reversal of expectation, Hendricks’ paintings, with their blank backgrounds and fashion focus, come out of a recent photographic tradition, while so many of the photographs in Personal Views come more directly out of the painting tradition, in which sitters pose with symbols of their worth.

Hendricks’ portraits also reference religious icons, an association that elevates his subjects to sainthood. Some of the paintings glow with an ethereal light; and some of them have iconic gilt backgrounds. Surrounded by nothing but ether, with no details of the urban environment from where they come, these subjects are well-positioned to communicate their self-worth with sartorial splendor. They come without pedigree and create their own individuality. It’s costume as self-invention. And Hendricks loves and admires them for being exactly who they are.

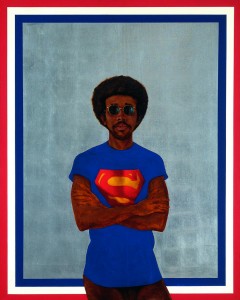

This is not art as fashion design; this is art with a political subtext. The scale is confrontational, grand and powerful at the same time that the figures are non-threatening. The iconoclasm in Icon for My Man Superman, a portrait of Bobby Seale, takes both Superman and Seale off pedestals, humanizing the cartoon, humorizing the man. Barkley Hendricks loves his subjects and loves people. It comes through loud and clear. He is legitimizing, embodying, making visible. It’s a gentle approach to a social revolution.

Sarah Stolfa’s, Zoe Strauss’ and Justyna Badach’s portraits at Gallery 339 may provide environment in the tradition of Rembrandtian burghers, but their subjects are not exactly burghers. not the usual powerful or moneyed class who can afford to commission Annie Leibovitz.

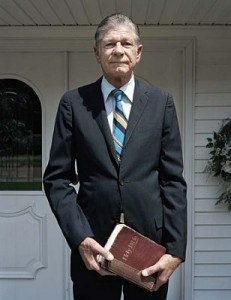

Badach’s photos of bachelors are sad, the men isolated in forlorn environments of their own choosing and creation. These photos have no lushness to them, but the question of who we are looking at and why is plenty of a draw, with or without the statements Badach displays with the photos.

In Stolfa’s current series on view, which references Robert Frank and Alec Soth, there’s a question of intention. She lets the subjects project who they are. But she cannot cross the social divide in the same way that she did in her portraits across the bar at McGlinchey’s. Stolfa means to disconcert her viewer. And I suspect she herself is disconcerted by the kitchen worker with the gun at her waist. In this sense, Stolfa’s portraits are less about the individuals, and more about a cultural divide between northern and southern values.

Not so in Strauss’s work, where the people’s faces become a roadmap away from Britney and Joan Rivers, a different vision from the media circus of what it means to be human. Strauss is the Walt Whitman of Philadelphia photographers, singing her love for an entire side of the culture otherwise ignored. But unlike the romanticizer Hendricks, Strauss keeps the hard-scrabble environment and the hard-nosed realism, be it no makeup or too much makeup.

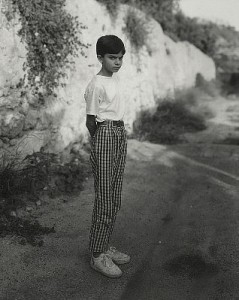

Also in the show at 339 are Andrea Modica’s sociological photographs of Italians who have been largely untouched by glamor shots and the notion of performing for the camera; Rita Bernstein’s painterly photographs that are less about portraiture than mood and light and material; Jessica Todd Harper’s portraits of middle-class comfort, which seem closest to the burgher portraits of the Dutch golden age of painting; and Nadine Rovner’s setups, which are less about the individual people and more about cinematic mise-en-scenes.

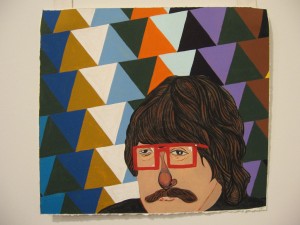

PS: I saw Josh Rickards at BYOTY at Little Berlin while I was thinking about the photos and Hendricks, so then I gave some thought to what Rickards is doing. He, like Hendricks, takes the subject out of a real environment. Sometimes the background is a blank color, but sometimes he creates a flat, abstracted environment that represents a milieu, a time and a place. And his stylized faces, which draw from craft veneer drawing, emphasizes the deadpan ordinariness of his subject. These are not so much personal portraits; they are pictures of a lifestyle and subculture.

Personal Views: Contemporary Photographic Portraiture in Philadelphia is up through November 14, 2009 and Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool is up to January 3, 2010.