Iraq has been front-page news for years and the Holy Crescent is central to Jewish and Christian scripture, so it’s surprising that some of the greatest treasures excavated there have been sitting in Philadelphia since the early 20th Century and been relatively ignored. The British Museum’s spectacular goat of lapis lazuli caught in a thicket of gold has a twin at the Penn Museum.

Iraq’s Ancient Past; Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery, a re-installation of the museum’s own collection, opens to the public on Oct. 25, 2009 at the Penn Museum; that Sunday will be a celebration with programs for adults and children. All exhibitions tell stories, and when much of this material was on an extended tour from 1998-2006, the story was of craftsmanship, luxury materials, in a word, art. The current story concerns their excavation and second life out of the ground, and explains why half of the treasure stayed in Iraq while the other half was split between the British Museum and Penn, who payed for excavation.

The unearthed goods from the royal tomb have been valuable to several generations of archaeologists. Identification of materials such as gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian confirms trade routes in the third millennium BCE, for none of the valued materials exist in Iraq; the only local materials were textiles and ceramics.

Two skulls from the excavation were recently studied with CT scans at the nearby Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; this revealed that the royal retainers hadn’t gone willingly to their death, as had been thought, but had been hit in the head, probably intentionally. Unfortunately C. Leonard Wooley, who directed the excavation, threw out other bones; scientists now use them to reveal a variety of information.

Donny George, former director of the Iraq Museum, attended the press preview and I asked him whether there had ever been controversy about exhibiting the human remains; he said never. They had been shown in Bagdad without problem.

Some questions can’t be aided by modern science. Queen Puabi’s gold headdress, like all the jewelry, was found as a heap of individual pieces and had to be reconstructed. It’s like a puzzle, but there’s no way to know if you get the right answer. Archaeologists believe the original reconstruction was wrong, and it’s not in the exhibition yet because the current reconstruction is still going on.

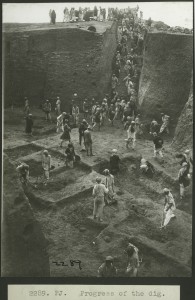

The exhibition includes period photographs of the excavation and contemporary newspapers which confirm that the discoveries were on a par with Tutankhamun’s tomb, discovered in 1922. Labels bring the dig to life. Midway through the work Wooley wrote: I’m sick to death of getting out gold headdresses. It also situates the excavation within the history of Iraq which only became independent in 1932. Wooley’s permit to excavate was numbered 1. Current law forbids archaeologists from taking home unearthed goods; all goes to the state (except for unofficial digs, or looting, which is a problem in many countries with valuable archaeological material). Donny George reassured me that Iraq has been happy to work with scholars, providing samples for examination and shards for study.