Imaginative Feats Literally Presented; three fables for video projection, an exhibition of Jeanne C. Finley and John Muse’ work is on view at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery through Dec. 11. Muse teaches at Haverford and Finley at California College of Art and they have collaborated for many years. Like all fables, theirs deal with big ideas: vulnerability, fear, family, safety, truth and fiction, control. The three works read as chapters of the same story, all set in the present when America is at war. The exhibition leaves visitors uncomfortable, but these are not bedtime stories and they are not addressed to children.

The first piece, Lost (2006), is the simplest technically and structurally: a single channel shown on a small screen, with headphones for the audio. An unseen army chaplain reads from his diary and we learn he’s in Iraq. We see a landscape obscured by fog which lifts slowly, revealing cliffs that cannot be Iraqi. He tells of conflict; not of battle, but of his own attempt to deal with the consequences of war. It adopts a documentary format but doesn’t quite play by the rules.

Guarded (2003) places the viewer in the middle of a moving and unstable circle of images that turn to the steady, repeated thump, thump, thump of a date stamp. The imagery is mundane: a child out of doors, an empty fair ride, a wedding, a woman walking, someone counting dollar bills. A text appears in several registers and with effort we are able to read what are obviously emergency preparedness instructions written in the impersonal voice of authority. The instructions are palliative; we no more believe that they will save us than we believed that crouching under our school desks would protect us from a nuclear attack during the Cold War.

Flat Land (2006-09), two video projections shown back to back on one screen, presents the coping mechanisms of military families when the father is at war, told by the families themselves. Finley and Muse’s compelling work offers no fixed, editorial point of view. It carries no obvious message other than the reminder that if we choose to ignore the larger issues that surround us, that is a choice; we are responsible for our own stories of denial.

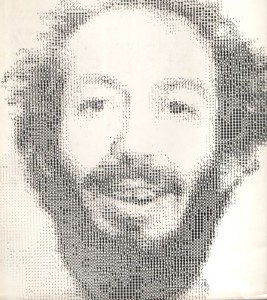

Hollis Frampton ‘s magnum opus

Last weekend International House showed all seven parts of Hollis Frampton’s Hapax Legomena; I missed part two because it conflicted with a symposium at PAFA (more in a later post). But I was determined to see as much as I could; I’d long known of Frampton’s significance to experimental film. Besides, who wouldn’t want to know more work by the photographer who (with Marion Faller) created the homage to Eadweard Muybridge, Vegetable Locomotion (1975), which includes the unforgettable Tomatoes descending a ramp [var.”Roma”] and Apple Advancing [ver. “Northern Spy”]?

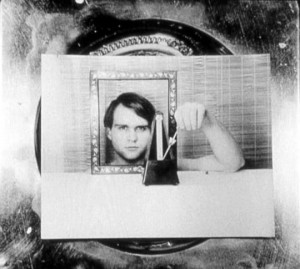

With Hapax Legomena Frampton created a multi-part record of his life and meditations on the possibilities of film. nostalgia (Hapax Legomena I) records the immolation of his early photographic work as Frampton tells the story of each image. We see the photo then watch as it turns to ash on an electric stove ring. The film is structured around the time it takes to obliterate each photograph, and by the second or third story it becomes clear that the narratives are off sinc with the images. Poetic Justice (Hapax Legomena II) is narration to the image of pages of the script, and Critical Mass (Hapax Legomena III) is an experimental cutting and re-cutting of the sort of domestic quarrel that has neither beginning nor end; it is somewhere between slapstick and Edward Albee.

International House shows enough films that intersect with the other visual arts that it should at least be bookmarked by all Philadelphia artblog readers.

On Saturday, December 19 at 7pm Chantal Ackerman’s 1979 film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles will be shown. For my review of an exhibition of Ackerman’s video installations, see here.