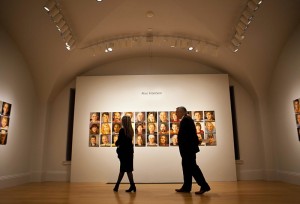

Last week I visited Portraiture Now: Communities, at the National Portrait Gallery through July 5, 2010, with paintings by Rose Frantzen, Jim Torok and Rebecca Westcott. It was organized around the idea of portraits of groups. Not group portraits, but individual portraits of people connected by familial relations, friendship with the artist or by virtue of living in the same, small community.

Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency would meet these criteria as would much of Elizabeth Peyton’s work. The curators implied that the ensembles were at least as important as the individual works. Most of them (with the exception of a commissioned series of 23 portraits of an extended family by Jim Torok) were initiated by the artists, who chose to paint the people around them.

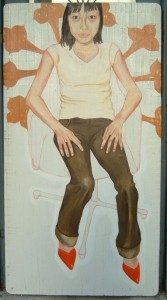

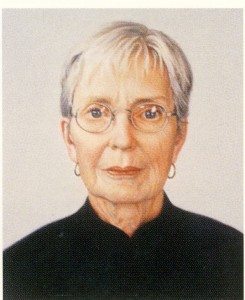

The full or three quarter length figures in Westcott’s portraits (in acrylic and oil on paper mounted to foamboard, 56″ x 24″) are all shown against white grounds while Frantzen and Torok adopt the conventions of passport photography: straight-on head shots, tightly-cropped, against blank backgrounds. Frantzen’s oils on board are 12″ square and Torok’s oils on panel are 5″ x 4″ and all three artists present their work unframed. The disparity in scale is significant in that Westcott’s and Frantzen’s work (particularly Frantzen’s portraits hung in large grids) make an impact at a distance whereas Torok’s miniatures, while hung on the walls, are much closer to Daugerrotypes or miniatures intended to be cradled in the hand.

Westcott painted her friends, many of them also artists who established a youthful community in Philadelphia involving shared studio spaces, often communal practice and a populist commitment to screen-printing and artists’ publications. On first impression Westcott’s interest in Alice Neel’s work is apparent: the frontality of sitters who meet the artist’s gaze, the slightly awkward draughtsmanship of the hands and broad palette of largely unmixed colors. But the paintwork is her own, beginning with drawing in red paint and continuing with thinned upper layers. She said she was influenced by the look of hand-painted signs although the matte paint, saturated colors, cream-colored, occasionally scraped-down backgrounds and slightly uneven edges of the mounted works give them the look of fresco paintings removed from walls. Westcott’s best portraits are extremely appealing as paintings in a manner that is not particularly fashionable these days, as well as records of a significant emotional bond between artist and sitter.

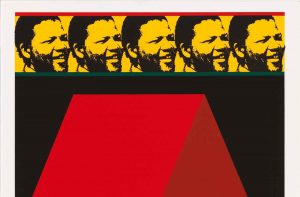

Frantzen conceived her series, Portraits of Maquoketa (2005-06), as a community portrait motivated by civic sentiments. She wanted to contribute to her small, Iowa home town, affirm that all of its residents were potential subjects of painted portraiture and bring them into her creative process. She set up a storefront studio, advertised for sitters and painted 180 individuals who were willing to sit for one, four to five-hour session. In that sense the work is a cross between a conceptual project and a series of highly traditional portrait paintings. The creamy, wet-into-wet paintwork records the immediacy of the project. Frantzen’s most interesting paintings are those the of older sitters; where the richer terrain of their faces brought out her best work.

Torok’s technique has some of the tromp l’oeil realism of 15th century Netherlandish painting and he is extraordinarily skilled at registering minute changes of light across the varying planes of a face. Once you get over being startled by his virtuosity, the emotional intensity he achieves in the strongest of them becomes their most compelling feature. Torok speaks of a democratizing impulse, which he associates with the uniform format he adopts. The large series, A Colorado Family, was commissioned by a family that knew of his portraits of his friends and colleagues and here, too, I thought the portrait of the matriarch (above) the most impressive. Among his friends is a portrait of Lawrence Weiner, whose expansive, white beard presents the sort of challenge Torok clearly delights in.

The paintings and sentiments of all three artists reflect an affection and respect for their subjects and an emphasis on group identity; the unframed presentation and pointedly casual dress emphasizes the personal nature of the work, made for the moment rather than for posterity. In looking at the exhibition I couldn’t help asking myself whether I’d want to hang a portrait of someone unknown to me on my walls, and couldn’t answer conclusively. Why is it that our interest in portraiture is overwhelmingly an interest in the subject, rather than the art?

Paintings of Revelation

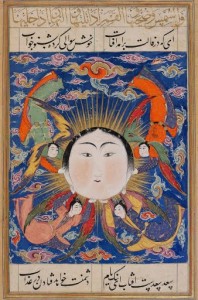

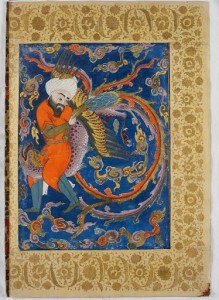

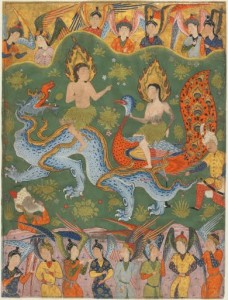

Falnama; The Book of Omens at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery through January 24, 2010 is the first exhibition ever devoted to a group of illustrated manuscripts used for divination during the 16-17th centuries in Safavid Iran and Ottoman Turkey. Only four, monumental copies of the falnama, or Book of Omens survive and they are brought together for this exhibition with loans from the Topkapi Palace Museum and collections across Europe and the United States. It will only be seen in Washington. While their style relates to Persian miniature painting these are on an entirely different scale, measuring as large as 26 x 19 inches.

The illustrations are splendidly colored and gilded and full of wonderful detail with an abstracting tendency to the landscapes, in particular; the flowers are distributed evenly across the fields in the manner of textile patterns and clouds fill skies at perfectly-spaced intervals. Most of the paintings were done in Safavid Iran and some of the artists in this area of crossroads were clearly exposed to Chinese and/or European art. The subject matter is wide-ranging: signs of the zodiac, historical episodes from the life of Alexander the Great, stories from literature, illustrations from the Koran, the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. As with most accoutrements to prophecy, their interpretation seems to have been left largely to the users, although modern viewers are likely to appreciate them as illustrations rather than as esoteric tools.

Hippocrates, the ancient physician who was learned in alchemy, astrology and magic is shown riding across the sky on the purple-speckled back of a mythical bird, the simurgh (above); it has gilded wings and a long, divided tail that forms loops in the cloud-filled sky. In another image the angel of death, a pale gray demon that breathes fire and carries a flaming mace, swoops down to grab a tyrannical ruler by the throat. The captured tyrant in this Koranic tale of pride being punished has barely dismounted and one foot is still in a stirrup. The scene is set at the gate of a glorious, walled garden where irises bloom and harpies sit in trees full of pears and pomegranates.

Perhaps the greatest surprise and delight are the paintings depicting biblical stories with a Persian cast. In an expulsion from Paradise (below), Adam rides a four-legged, blue, dragon-like serpent and next to him Eve sits astride a peacock as they ride over a carpet-patterned landscape. Both wear skirts of leaves and halos of flames and crowds of angels in contemporary Safavid court dress observe them with some surprise.

The exhibition includes a selection of related objects, among them several beautiful, steel standards pierced with patterns formed by protective inscriptions, divination bowls, and one of my favorites: a talismanic shirt which would have been worn as an undergarment, entirely covered with Koranic prayers running horizontally, vertically and on the diagonal and inset with numerological cubes. The amount of gold and costly lapis lazuli suggests it was made for royalty.

This is an extraordinary exhibition filled with a wealth of visual richness and interest. It offers a body of work previously known only to specialists and will appeal both to scholars who can appreciate the complex relationship between images, texts, and divination practice and generalists who enjoy imaginative and beautifully painted visual narrative peopled with figures from history, scripture and myth. Its sumptuous, fully-illustrated catalog includes essays by six scholars from various fields as well as the first complete translations in English of three of the falnama texts.