Post by Judith Stein

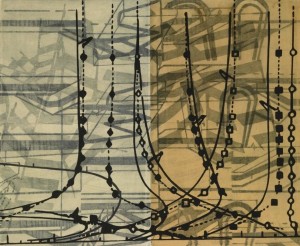

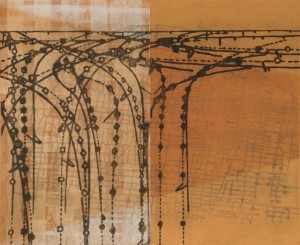

Sarah Amos is an artist with a consummate mastery of printmaking. In this new body of work, her third show at Cynthia Reeves Gallery in Chelsea, she pits macro against micro, playing bold, dramatic shapes against delicate forms and textures. In her handsome, large-format prints, shapes that resemble beaded curtains or louvered shutters both define the surface and tantalize, giving us a peek but limiting our visual access to the space behind and below. But once we navigate around these arresting, gatekeeper images, a seeming infinity of nuanced space opens.

Amos is an artist with a formidable command of media. To create her collographs, for example, her inner sculptor laminates layers of cardboard, constructing the physical plates and then pocking, scoring and marking them with a knowing eye. For any given work of art, she may ink up and print as many as a dozen different surfaces. And before she runs anything through the press, she first modifies and colors the paper itself.

After she completes the multiple printings, she goes back into the image and draws and paints on the surface. It is the collective power of these actions that impress me as a viewer when I look at her art—I don’t need to know the details of its fabrication. Yet I find them fascinating.

Last spring, Amos and I sat on shanghaied office chairs in a quiet corner of the Reeves Gallery, to look at her new etchings and collagraphs that were spread out on the floor.

Maps and textiles

Judith Stein: Please talk to me about your process. I see that you are working on a somewhat smaller scale now.

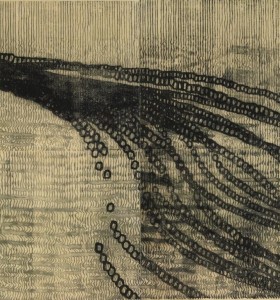

Sarah Amos: I still favor Shiramine paper, a very heavy weight Japanese paper with a rag content, that I pre-stain with a tint. Also, I’m using glue and carborundum dust, which has a fantastic tooth, and a rawness that I like. It picks up the ink very well. I like the glimmer from the mineral in it, and the resulting diffused line, as if you were drawing in sand.

Previously, I regarded the printmaking as the set design, and the drawing as the actors. The ratio of the two media has shifted in this new work, although in some there is more drawing, and in others more printing.

JS: Doubleround is a very suggestive composition. One of your sources is an aerial view of a medieval village, which you overlaid with circles. I read them variously, as seeds, balls, or the letter “o”. Some look like earrings.

SA: I’ve been thinking about African, Japanese, and aborigine textiles. I am drawn to their very fine detail. My recent works are more painted then in the past. I allow for happenstantial drips and stains—these spontaneous effects are more interesting to me now then in the past. I love two very distinct surfaces, the linear clarity of one playing against the softer carborundum.

Film and repetition

JS: The vertical configurations in Main View evoke a film strip. Curiously, they call to mind Joan Jonas’ seminal video Vertical Roll (1972), with its jumping picture frame, and its repeating horizontal black bar between images. Looking at this diptych, my eye wants to go up and down repeatedly, combing through it.

SA: Repetition interests me a lot.

JS: Lines of dots have been a consistent design element for you, an influence and an homage to the dreaming paintings by the aboriginal artists of your native country, Australia. They are present here as well, in different incarnations.

SA: In the layering of images in Main View, I’ve printed on top of an earlier print, bringing along—yet burying—some of that old detail. Having the dots is like dragging your old family members with you.

JS: In Earlier Territory, there are big black sections that resemble the cold and warm fronts in the weather map.

SA: Flux is an underlining theme in all this work—the intersection of the landscape and the forces of nature, such as out-of-control weather.

JS: I’m thinking of film again. For me, some shapes in Earlier Territory encode a cinematographic reference: they resemble the sprocket holes on the edge of a film reel.

SA: I would love to animate these drawings. I could see these things moving and rolling over great surfaces of differing scale and plane.

JS: You’ve mentioned that some of your source materials are aerial maps that diagram people’s walking patterns in various cities.

SA: They are beautiful drawings, paths seen from the air, these repetitive marks that create a pattern on the landscape.

JS: In Salt: A World History, Mark Kurlansky points out that when you look at a map and study the whimsical, nongeometric pattern of the secondary roads of almost any place in North America, you see that the towns seem interconnected haphazardly, without any scheme or design. But that’s because the roads began as widened footpaths and trails, which were originally cut by animals looking for salt.

In other works, such as Striped Slip, King Tide, Close Range, Wide Numbers, Rope Weed, and First Blush, you use ghost images. How do you call up these “specters”?

SA: Every inked plate will deliver three printings. I use all three: from super dark, to medium, to light. On any printmaking day, I spend six or seven hours inking all the plates first. Then I go to the press, because everyone gets printed once, twice or three times on each surface, as a way of building it up. A little bit of each language is carried over to the next one and so on.

A library of 550 plates

JS: So any given piece of paper could receive, say, both the vivid first printing of one image, and the third printing—or faint ghost—of another?

SA: Correct. In the past, I printed perhaps 30 or 40 different plates on the same surface. Now there are 10 to 15 passes of very thin veils of oil paint, printed on dry paper, which somewhat repels the ink. I can work on that surface a lot longer than if it were wet.

I like the idea of recycling the images from old to new. I have amassed and categorized nearly 550 plates, my own physical library of images. I store them vertically in big racks in my studio.

JS: Wow. If you think about any specific one, you know where to find it, like pulling a book off the shelf!

There is a tiny, tiny perforated line underneath the more prominent image in Knot Stopper.

Roulette and chance

SA: Most of my work has this surface, which I create with a roulette, a very sharp tool for marking dress patterns.

JS: You have to be keen-eyed to see these minute lines; when they overlap, they resemble rails or crossings. As the knotted lines tumble down the face of paper, they give the impression of weeping willows, or some organic matter, graciously falling.

SA: I create them with a roulette, one of my favorite tools—my mother is a fashion designer and I enjoy the fact that she uses it as well, but for different ends.

If you saw an image of me at work, I’d be standing in my socks, wielding a five-foot-long pole with the roulette strapped to the end of it, making big, sweeping movements on the plate as I wheel the stick. It is very physical. I am walking back and forth all over the plate surface, gouging and raking. My dog might be standing right beside me in the middle of the piece. I’m just careful not to run over his feet!

JS: What role does chance play in your work?

SA: For example, you can see where the ink hasn’t taken in the wide middle section of Seismic Chatter. This unplanned result adds to the richness of the image, a dimension I couldn’t have done myself. This is that element of surprise that I still get, after all these years of making prints. Ninety five percent you know what you are doing, and then the last five percent is fantastic surprise.

SARAH AMOS “New Territories”

October 15-Nov 14, 2009

Cynthia Reeves Gallery

535 West 24th Street

New York, NY

Discussion with the Artist, Saturday, November 14th 3 – 4 PM

Also, if you want to see a piece by Sarah Amos closer to Philadelphia, catch her in A Complex Weave at Stedman Gallery, Rutgers Camden.

–Judith Stein is a Philadelphia-based writer at work on a biography of the late art dealer Dick Bellamy, “the eye of the sixties.”