Chris Ofili

Foreword by Peter Doig, conversation with Thelma Golden, contributions by David Adjaye, Carol Becker, Okwui Enwezor, Cameron Shaw and Kara Walker

hardcover, 272 pages, 200 color images and b&w drawings, 2009

$85

Rizzoli New York

This gorgeous coffee table book about the works of Afro-British artist Chris Ofili is a love affair from start to finish. Great photos of the works — in situ in gallery spaces and in amazing closeups of the rambunctious details — make for hours of satisfactory page-turning. There’s just enough words and pretty much the right words to keep the volume chugging along. But really, you can crack the book anywhere and get sucked in to the artist’s oeuvre.

Ofili is known best in the US for his “The Holy Virgin Mary” the painting that almost closed the Brooklyn Museum’s “Sensation” show in 2000. With elephant dung and collaged photos of female genitalia, the painting of an African BVM was inflammatory to then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani and to a lot of others, one of whom smuggled white paint in to the show and besmirched the painting because “It was blasphemous.” Carol Becker’s essay deals with the political controversy surrounding Ofili’s work and puts the artist in the context of “the trickster” (see Lewis Hyde’s Trickster Makes This World–Mischief, Myth and Art) — someone who mixes sacred and profane to “stir the pot.”

Okwui Enwezor’s impassioned essay about nationalism and colonialism in the art world uses Ofili’s 2003 Venice Biennale installation as an example of post-colonial reclamation. Ofili was the British representative to the Biennale that year and his pavilion recast the British flag in red, green and black and his paintings showed a re-telling of the Garden of Eden story with black figures in an all red, green, white and black world. Among other things, Enwezor also states the obvious, that Ofili is a superb colorist. (P. 156) Amen.

The artist, 41, seems to be heading into transitional territory in his recent paintings (and sculpture) from 2000-present. The works — gone are the riots of dots, the humor, the collage elements — feature colorful Mattise-like nocturnals with figures convening with each other, the moon and the cosmos. A suite of blue-on-blue works, which don’t reproduce particularly well because they are so dark, are more interesting for being inscrutable. In an essay with Thelma Golden, the artist confirms he’s in a new creative zone indicating he’s now residing in a land (Trinidad) where mysticism and the night are huge elements. He sounds smitten. As for his black-power content, he says it’s exciting to be young and to change and to explore and expand so that…”the work doesn’t have to explicitly be about the black or looking black.” (p. 246)

Native

by Mona Kuhn

Essay by Wayne V. Andersen

Text by Shelley Rice

96 pages, 65 color plates, 2009

clothbound hardcover with dust jacket

Steidl

$75

This book of landscape and portrait photographs represents Mona Kuhn’s exploration of her roots in Brazil. The photographer, who was raised in Brazil but lives in the US and studied art at Ohio State University and San Francisco Art Institute, casts her work in terms of poetry and dreams. Her deep jungle landscapes and some fuzzy almost abstract interiors are highly poetic and dreamy — and beautiful if not unique. But the portraits, with one or two exceptions, snap you right out of the dream and into the land of contemporary portrait photography where they do not stand up to portraits by, for example, Rineke Dijkstra, who seems an apt comparison. Kuhn’s pictures of nubile young men and women posing self-consciously in an interior of what looks to have been a nice old house, now abandoned but for a few stools and a mattress (with sheets) on the floor, don’t have an erotic charge and they don’t quite read as documentary either (these are not tribespeople who live sans clothes — they are acquaintances of the artist’s who agreed to pose nude for her). Kuhn’s portraits most remind me of Gaugin in their love of and fascination with the native “other.” If the book had separated the non-figure works from the figure works– and edited them down to the one or two scenes of humans in nature, then perhaps the idea of the artist’s journey into the heart of darkness would cohere and fascinate. As it is, the suite of works feels serendipitous and tossed off.

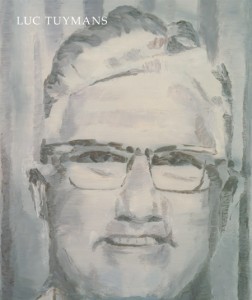

Luc Tuymans

edited by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Wexner Center for the Arts

DAP/Distributed Art Publishers, New York

clothbound hardcover with dust jacket

228 pages, 175 color images, 2009

$60

The catalog for Belgian artist Luc Tuymans major US mid-career retrospective (just finished at the Wexner Center and opening Feb 6 at San Francisco MoMA) is an excellent tool for understanding the artist’s challenging works. (Lauren Whearty previously told you about the show). In the book’s preface, the two exhibit curators, Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth, explain that the artist is a sort of history painter. He uses events from the past — the Holocaust, Belgian colonial history, old medical textbooks about pathology — to make inter-related paintings in series that are conceived of to be installed together “in a highly self-conscious even curated, manner.” (P. 10) To see an individual Tuymans painting is to miss the cumulative aspect of the series in which volumes may be spoken in the interstices.

Tuymans is aware of the allusive yet unclear aspects of his works, and he welcomes discussion and writing about his works feeling that the discourse becomes almost one with the paintings, enhancing, embroidering and amplifying. The artist’s whited-out works are very much about time. Neutered of color, the works convey the passage of time in their thick pastiness, like dust forming on surfaces long abandoned or film built up on windows. And while they are not ironic, the paintings are the embodiment of postmodernist cool distancing. (P. 19)

The book considers the various paintings in their series and each chapter is preceded with a painting fragment — a cropped view of a man’s eye behind glasses as featured in one of Tuymans’ paintings. The repeat of the supersized eye staring at you is funny when, at last, you realize it’s part of the book design. But the big eye is also effective in reminding you of the artist’s serial repetitions. And each eye blow-up nicely showcases the short horizontal brushstrokes the painter prefers.

Luc Tuymans

Art Gallery of York University, Toronto

105 pages, 1994

$35

Fifteen years before the current Luc Tuymans’ retrospective, the artist had another traveling look-see whose venues included York University in Toronto, the ICA in London, the Renaissance Society in Chicago and Goldie Paley Gallery at Moore College, Philadelphia. There’s a slim softcover catalog for that show (also available from York at the link above) that I got from Moore Galleries director Lorie Mertes a while ago, and what’s interesting is that the essays and commentary in that little book — which cover many of the same paintings in the 2009 traveling show — do so with much the same kind of commentary. My favorite essay, for its unencumbered look at a then-unfamiliar artist is Peter Schjeldahl’s “A Little Hell: Introducing Luc Tuymans” in which the writer, with “slight” knowledge of the artist, calls Tuymans’ paintings a “faintly childish zone, a psychic toyland ” and praises Tuymans’ ability to deal with “the titanic and the tiny of human experience” — namely the Holocaust — in his “small, pale, doodlish pictures.”

While I hadn’t read the word in the 2009 catalog, Gregory Salzman hits it in the first paragraph of his essay — perversity. It’s a word (and concept) that seems appropriate for paintings so obstinately locked in mystery. Salzman compares Tuymans works to Kafka, which also seems right. “(Tuymans’ art) shares many characteristics of Kafka’s writing: above all its perversity, but also its violence and morbidity, its hostility to authority, and its adoption of the language and methods of rationalism to subvert its authority and to expose its aridity.” (P. 11)

Interestingly, Tuymans credits Belgian painter Raoul de Keyser as an influence. And de Keyser also has a Philadelphia connection — he too had a solo show at the Galleries at Moore in 2000, guest-curated by Gregory Salzman.