Christian Boltanski’s installation at the Grand Palais in Paris entitled “Personnes” is a monumental culmination of the artist’s lifetime of work. Situated with perfect harmony in the giant, airy, steel and glass structure in the heart of Paris, Boltanski’s show offers a lean view of “homo-industrialis” and his output in the face of history.

After we pass under elegant stone arches and through the filigree of the Grand Palais’ doors we hit a wall. Its height blocks our view of the Palace and it consists of identical, stacked, rusting boxes each marked with a meaningless number. They don’t have openings. On top of the wall is a row of what appear to be reading lamps inviting us to look closely and become cozy with a source of information. But of course the lights are far too small to light the whole wall and at our level we are almost in darkness. This is the Boltanski coda, compartimentalization , anonymity and humanity reduced to small homogenous spaces.

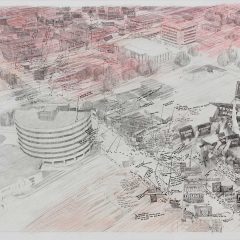

We walk around the wall and seem to enter a factory. The wall of boxes has been replaced by a wall of sound. A most unexpected spectacle sits on the far side of the palace: a 10 metre high mountain of colored shreds of fabric over which is a crane that plunges a giant red claw into the mound. The claw rises up with a mass of dangling shreds and when it reached the crane arm it stops for a moment before releasing the fabric which falls with flapping grace back onto the pile.

To get to the pile we pass through a grid stretching from end to end of the palace. It consists of neatly arranged squares of jackets and other outerwear lying flat on the ground and on each other. It is a thin layer like a dusting. We have no idea who wore this stuff. Each square is lit with a neon light and contains its own soundtrack of industrial noise like a unique workshop/ensemble within the factory . Is it trains or just machinery in general?

At the foot of the mound we realise that the shreds are all manner of used clothing. The claw descends and hovers over the apex not able to decide where to clasp next. There is no transfer from one pile to another. There is no further redistribution throughout the grid. The industrial action is Sisyphean and although the sound suggests heavy industry working at full capacity we see nothing either being produced or destroyed. What kind of a factory is this? Who’s in charge?

To the side of the pile Boltanski asks us to participate in a paralell project. He asks to record our heartbeat so that he can compile the heartbeats of humanity. Here we learn that the industrial sounds are in fact a montage of human heartbeats.

Boltanski is fascinated with history and the Shoah in particualar. The Shoah was the first time that the killing of humans became industrialized. One of its legacies is the human quest to remember that such things happened in order that they may not happen again. But of course humans forget. They need to after such acts of folly otherwise they couldn’t continue to function. This show suggests that there doesn’t seem to be any more space available for us to remember the disappeared. There is no demand for this clothing or for the stories of those who wore it. We will buy new clothing which will be added to the pile . . .

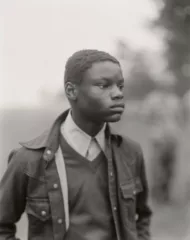

The grid and its lighting evoke large sorting centres ( aka refugee camps). These centers are the portals through which the displaced and disinherited usually pass. They are usually but not always gates to Hell . . . or to nowhere. Boltanski, aided by winter, twists our concept of Hell. It is no longer a place where we burn but rather a place where we lose our heat. The coats on the cold cement floor promise warmth but the clothing is as cold as the ground. Humanity’s great disappearances become a thermal phenomonon. Pictures of recent history flood the mind. All of these “no bodies” once stood naked in line somewhere, on the way to total heat loss.

This show pits our fascination with industrial processes against the horror of dehumanisation via the same processes. The great machine here is the human heart, our metabolic furnace. This heat produces the zone of bodily heat in which we flourish. But it can be used to produce mortal cold as well. As long as our hearts beat this kind of factory will be running somewhere. Even though history furnishes us with large supplies of this kind of sordid history there will always be some kind of demand for this output.

‘Personnes’, Grand Palais, Paris, until February 21. www.monumenta.com