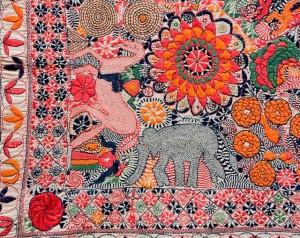

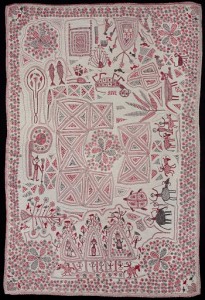

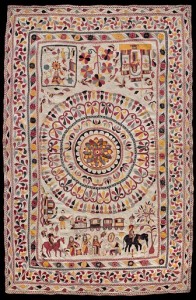

Kanthas are delightful and appealing vernacular textiles, fashioned from of bits and pieces of worn clothing and embroidered with figurative designs by the women of Bengal (now divided between the Indian state of West Bengal and Bangladesh). Some of their charms are akin to childrens’ book illustrations, others to comic books and vernacular art of various origins: lines of dancing girls as tightly coordinated as the Rockettes; plants, birds, beasts and humans interlocked like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle; elephants and horses carrying all sorts of riders and at least one horse sitting astride a man.

My guess is that they would delight Chris Ware, Alexander Calder and Paul Klee. The fact that these are an unfamiliar form from a little-known area should in no way discourage a broad audience.

The oldest known examples of these mostly anonymous works date from the late 19th century and were made both as gifts and for household uses such as seating cloths, blankets, and wrappers for significant objects. The enchanting exhibition, Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through July 25, 2010 presents 44 kanthas in the first exhibition devoted to the form outside of South Asia.

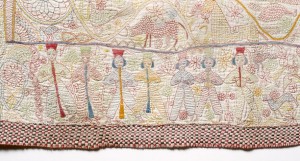

Beyond their obvious appeal to viewers interested in textiles, these richly-figurative works will interest others for their various solutions to both patterning and narrative design. Some represent religious imagery (Hindu and Muslim), others daily life including household activities, satires of family relations, specifically-represented flora and fauna and aspects of modern life such as gas lights, trains and hot air balloons. They tell of family relationships, shared traditions, and personal and idiosyncratic means of expression. While knowledge of their stories (all explained in the wall labels) will enhance their understanding, appreciation of the lively human and animal figures requires no specialized knowledge.

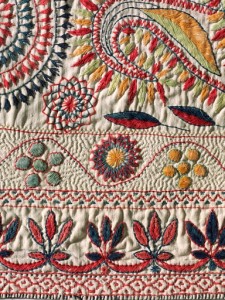

The embroideries share regional characteristics of palette (all are on fine white cotton worked with mostly red, blue and black thread), decorative motifs (kalka or paisley forms, lotus blossoms often used as central medallions, and borders embroidered in imitation of woven jacquard ribbons complete with the effect of stripes created by colored wefts), stitches (largely simple running stitches and satin stitch), and background pattern created by the finely-stitched quilting employed to hold the multiple layers of thin cloth together. They vary as to fineness of embroidery and sophistication of draughtsmanship.

The exhibition is drawn from two collections: that of the scholar and curator of Indian art, Stella Kramrisch, who appreciated vernacular art long before most scholars (not so surprising for the Viennese scholar, since artists in Germany and Central Europe had mined the work of children, folk and self-taught artists since the early 20th century), and that of Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz who collect the work of self-taught artists and found similar qualities of immediacy and personal expression in the quilts. Kramrisch donated her collection to the PMA and the Bonovitzes have promised theirs to the museum.

The exhibition, curated by Darielle Mason, includes the wonderful feature of a slide show of greatly-enlarged details, enabling the language of their stitchery to be clearly seen and enjoyed. It is accompanied by a beautifully illustrated and produced catalog, Kantha; the Embroidered Quilts of Bengal (ISBN9787-0-87633-218-4) with essays by numerous scholars that approach kanthas from a broad perspective including their original social functions, early institutional collections and their relationship to national awareness, regional motifs and identity, their places in women’s lives, their techniques, and the history of these two specific collections.