Traditionally when we talk about fiber, we talk about not just its drape but also about its hand. Fiber is mostly meant to be touched. And if you come from a long line of Jews, from a people who have historically long been in the rag and clothing trades, when you see a piece of fabric, you have an urge to “feel the goods.”

So it’s not surprising that these were thoughts I had when I went to Wimpel! Wrapped Wishes, a small fiber-based show of 12 works at the Philadelphia Museum of Jewish Art in Rodeph Shalom Synagogue on North Broad Street.

Curators Matt Singer and Wendi Furman invited 11 artists–from the internationally acclaimed Polly Apfelbaum to the Philadelphia-based Lance Pawling–to make contemporary art wimpels inspired by the traditional German-Jewish ceremonial cloth, a sort of scarf talisman used at life ritual events like circumcision ceremonies, bar mitzvahs and weddings.

Apfelbaum’s 5 wimpels in one anchored the back wall and thereby the whole exhibit with its explosion of color and velvety texture. The gorgeous lineups of marker colors and patterns–each mark a mini-Rothko–reminded me of knitted winter scarves, perfect for the gray wintry day that I stopped by. The out-of-line edges turned the “scarves” into well-used objects or people with quirks. They had a tenderness to them as well as a joy in their exuberant, saturated colors.

OK, so it’s easy to love Polly Apfelbaum, you say. What about the others in the show?

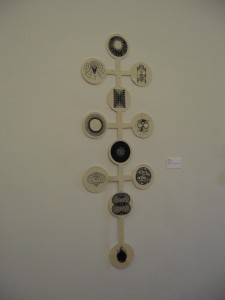

Well, since you really want to know, Estelle Kessler Yarinsky’s Dor L’Dor–From Generation to Generation, has an utterly different art historical background. Whereas Apfelbaum’s explosive colors and repetitive lines bring a feminist conversation to art historical traditions like Minimalism and Post-Minimalism, Yarinsky is working both in Judaica and women’s craft traditions–sewing, applique, decorations. She has created a wimpel that names her grandchildren and their individual accomplishments, represented in buttons, pins, images, embroidery, all held together with a sculptural stuffed red tube that becomes a cartoon thread or artery reaching across the generations.

At the top, sits the grandmother admiring her handiwork. She’s a stuffed doll well-dressed in a skirt and high heels , at once chic and grandmotherly, doting and smiling. This wimpel, teeming with life and love, begs to be fingered and pored over. And the Hebrew, indecipherable to most of us mere mortals, seems like no impediment to understanding what this piece is all about.

A very different craft tradition generated Leslie Sudock’s Kamia Lilith (Lilith Amulet) and Seyag ha’shoshanim (Hedge of Roses). These felt wimpels, which look like torah bindings (a traditional wimpel function), are also from a craft and clothing tradition–the making of felt. But where Yarinsky’s wimpel is ebullient and juicy, Sudock’s are austere and stern, with their raised Hebrew lettering and thorny sculptural shapes challenging to fates to be kind. Again, tactility and beauty and mystery won the day–these had both.

Again, it seemed to hardly matter that words here were in Hebrew, although the wall labels did translate.

I wasn’t so intrigued by the more literal interpretations of wishes and Biblical passages. Nor was I intrigued by fabric that seemed so separate from bodies.

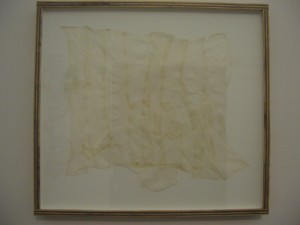

Daniel Heyman sidestepped fabric altogether by using strips of sheep casing. In so doing, he avoided the necessity of making fabric objects that are touchable. Yet he implies touch and vulnerability in his terrifying Tender Wrapping. The skin quality of the material refers to the lost bit of tender skin taken at circumcision as well as to a diaper (wimpels were often sewn from circumcision swaddling cloths) and the Torah, written on sheep skin. The piece was the surprise of the show, using its hands-off framed presentation to emphasize the sense of something precious being taken. The coherence of this piece (I could barely look at it because it is so effective) is shocking.

Others in the show are P. Timothy Gierschick II, Kym Hepworth, Tristin Lowe, K. Pannepacker, Lance Pawling, Alexander Stadler, and Jane Trigere.