At this moment when women Pop artists are looking powerful at University of the Arts, two women artist who have taken quite different approaches to survival and domination in a male art world are showing at Locks Gallery.

Diane Burko first made her mark with cool, but sublime, enormous paintings of mountains, based on photographs she took from an airplane (piloted by James Turrell, the master of cool with sublime). I have known Burko since we went to college together, and since we both began working at a time when women were struggling to move out of the kitchen, I have rightly or wrongly always interpreted that work as a statement of her right to compete with the big guys of that time–Ed Ruscha comes to mind. Either way, Burko’s mountain paintings are breathtaking and vertiginous, and cool, in the style of that era.

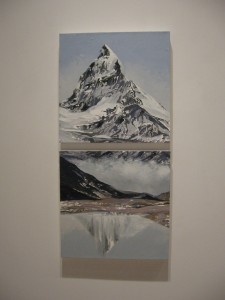

Many bodies of work later, in her show The Politics of Snow now at Locks, Burko returns to mountains, and again uses photographic sources, but gives us something quite different. It seems to me these mountains are less about her. These conceptual paintings are of two minds–alternately passionate and cool. And the concept, documenting the bifurcation between sublime nature and the threat to it posed by global warming, is expressed in the different modes of paint handling as well as in the use of multiple canvases depicting the rapid changes in each scene over time–diptychs and triptychs revealing the encroachment of water where once there was glacier.

The paintings are based on historic and contemporary scientists’ photographs documenting the before and after views. Burko obtained many from the U.S. Geological Survey, Glacier National Park archives and elsewhere. She gives the photographers credit in her titles–an act that is not only feminist in its embrace of collaboration but is also legally correct, not to mention in the documentary spirit of the work. (She also asked for permission from the scientists, who, she said, were pleased to give it). Although she has transformed the photos by cropping or shifting colors, she remains true to the scientific, documentary intent.

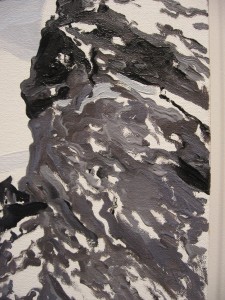

In the paintings, and in the paint, is a battle of aesthetics. The peaks, clouds and skies are magnificent, sublime, beautiful to look at, both from close and afar, the paint put down in sure, juicy squiggles and smooth diaphanous clouds, the white of pristine snow emerging from beneath and between the paint as untouched white ground on canvas. On the other hand, the encroaching waters are painted with a cold anger, a refusal to paint them as something beautiful. The water is a stain, an invading blot–flat puddles of Dr. Seussian ooblek painted in thick smears.

The colors in these paintings are largely from Burko’s imagination, since the sources are sometimes black-and-white photographs. The resulting colors are at once beautiful and disturbing. The light and atmosphere, even in this semi-real world, are gorgeous and chilly–but alas not chilly enough to keep the ice from melting.

On the third floor at Locks are Burko’s photographs of nature. Her eye for texture is unerring and her exploration of the margins where contrasting environments meet–water meeting lands, footprints in otherwise undistrubed terrain–make these photos a nice pairing with the paintings. By the way, both the photos and paintings were selling well–many red dots, a few blue ones.

The documentary vision of the paintings, however, reach to a larger story. Like the great Sublime landscape painters extolling the power of America, Burko here is making a political statement about what the landscape means. It’s a sad story being told more and more often by artists concerned about what’s happening to the world around us, as in Joy Garnett’s paintings, for instance, and in Alan Burtynsky’s photographs (now up at the Berman Gallery at Ursinus College). Although Burko has long painted the environment, here she is painting about loss. Hers and ours. That, and the march of time ,and the folly of humans gives these paintings their urgency.

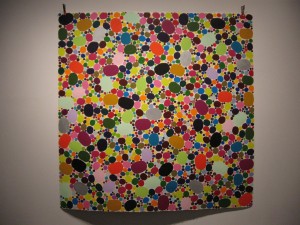

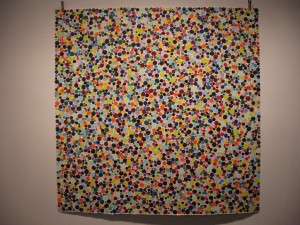

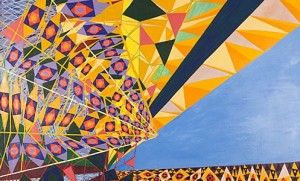

The junior and more radical artist of the two, Polly Apfelbaum, has used women’s materials, domestic references and body references in her groundbreaking work of fallen “paintings” of color-stained fabric swatches covering the floor. The work at Locks in her current exhibit, Color Notes, is less startling–less startling because it is on rectangular paper hanging on the wall. But even these prints suggest female concerns with decoration and exuberant warmth and color.

The woodblock print abstractions make me think that Op Art has come a long way, baby. Apfelbaum overthrows Op’s geometric decorum for explosions of color and irregularity, turning her heel on geometry and mathematical symmetry–on linear thinking.

My thinking about Op started well before I saw this show. I had stopped by Locks when the Sue Spaid-curated show Microfibers was there, and while I was looking at work by Laura Watt, I started thinking that her work was also a new, anti-geometric take on Op that came out of some female mindset that was webby and anti-grid. So when I saw Apfelbaum, I decided to declare this a trendlet. It’s the new Op.

Apfelbaum’s op pieces (I’d describe only four of the as Op) are next to her Pop flower prints (also unique prints). The titles suggest the 1960s and sex–i.e. the same era as Op–and like Marimekko floral prints, they are decorative and attractive. Although the flowers have many of the hallmarks of the abstractions–power color, texture, hand-made irregularity–they are less engaging and more predictable–except that in Love Park 19, the black hole flower in the center subverts all assumptions. (I know I’ve seen some of the Love Park works at Locks before).

I know there’s some idea going around that we are all post-feminist, but it seems to me to be not quite true. For all the acceptance of decorative work and work in traditional women’s craft media, women are still underdogs in the art world (the numbers prove it). But these are two women who have prevailed with the excellence and boldness of their work.

Apfelbaum’s exhibit and Burko’s photo prints are part of Philagrafika.