If you’re still thinking there’s a big divide between art and crafts, the 7th International Fiber Biennial will set you straight. Much of the work reflects social and artistic concerns and all of it is beautifully made. The exhibit, at Snyderman Gallery, features fiber art from 61 artists, who come from as far away as Denmark and Korea, with 15 of them from the Philadelphia area.

Among my favorites are two pieces about America’s long-term contentious issue–race. One is from a white artist, one from an African American artist, and as always, the subject is loaded with feelings.

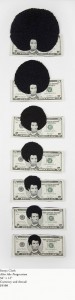

The African American artist, Sonya Clark, has stitched a growing series of afros onto the Abraham Lincoln etching on five-dollar bills in her wry piece Afro Abe Progression. (I’m sure this is illegal, but it’s a darned good use of money). The afro grows until it becomes a black shrub that dwarfs Angela Davis’. There’s the obvious relation to Ellen Gallagher’s visceral pieces of pomade-like goop for hair, but Clark uses a light touch here. Plus she gets in loads of content, from population shifts to financial power to black power. Abe stays Abe and does not morph into our current president, although I imagine Obama was part of the inspiration for this. The piece hovers between triumph and wariness.

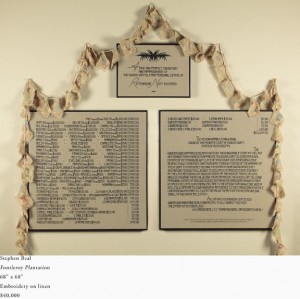

Whereas Clark keeps her serious subject light, Stephen Beal, a white guy, does not, although both use needle work to make their points. Here’s the back-story behind Beal’s monumental piece: He discovered, via Google, that his great-great grandfather Rittenhouse Nutt was a slave holder. The Rev. Samuel Turner Jr. of Memphis, Tenn., it turns out, had the same great-great grandfather. Turner, who is a lawyer, discovered a document in a Mississippi courthouse that confirmed his family’s oral history–that his grandmother Frances Nutt was both a slave and a granddaughter of Rittenhouse Nutt. The two great-great grandsons met via Google. And Turner showed Beal the document, which itemized the estate of Fauntleroy Plantation owner Rittenhouse Nutt. Turner’s 16-year-old grandmother Frances Nutt was listed in the estate inventory.

Beal cross-stitched the deed text onto three somber rectangles, forming a sort of grave stone. He also cross stitched prayer flags in red, white, yellow and blue for each of the slaves named in the inventory, draping them over his memorial. Slaves and livestock are included with their monetary value in the inventory, including Old Millie, at 76 valued at zero, i.e. less than a table or a chair, let alone a hog. The piece is stark, unbeautiful (although meticulously crafted), and deeply moving.

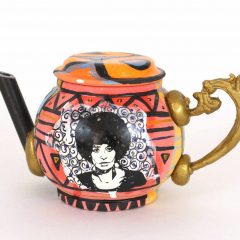

A third piece about race is by Joyce Scott, who is always excellent and is the only other African American artist in the show. Her grotesque, small beaded sculptures, which combine comic and outsider aesthetics, are pointed and ambiguous all at once. The one here is no exception.

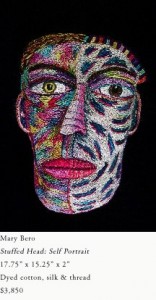

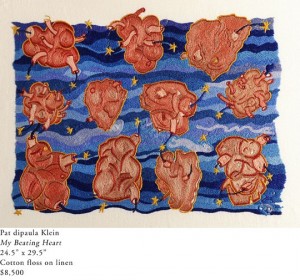

Identity is a big theme (isn’t it always), in other works as well. Mary Bero’s self-portrait, a stuffed and stitched head–puzzling, expressionist and 3-D all at once–gets at an unusual, arresting self-image. In contrast, Kate Anderson’s sweet little knotted house, also 3-D, uses stylized kitsch imagery to express identity and emotions. Pat dipaula Klein’s grid of hearts floating on a watery firmament gathers momentum from the turbulence of the stitching–a starry night of survival.

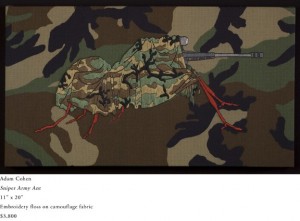

Broader social themes appear in Adam Cohen’s Super Army Ant, which we saw at Pulse last year. He uses comicbook vocabulary and embroidered camouflage fabric to make a political statement. And Katie Henry’s whimsical Music Together embroidery of animal-headed girls strumming on a park bench captures a social truth framed in an embroidery ring.

The show includes some fabulous clothing, embroidery, quilting, applique, macrame, the works of expected materials. And then there are the less expected materials:

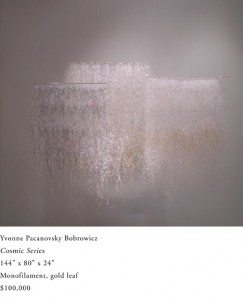

Pat Hickman’s stitched gut sculptures range from droopy to elegant symmetry, and evoke bodies and vulnerability–and Eva Hesse. Yvonne Bobrowicz’ frothy sculptures capture light with strands of monofilament. Amy Orr continues her credit-card quilt series, taking on China and the economy. C. Pazia Mannella goes for a pieced zipper boa (I had seen this one previously at Fleisher-Ollman) and paper take-a-number ticket leis.

In addition, there’s work here by other luminaries such as Lia Cooke and the fabulous Ed Bing Lee, who has pushed his wizardry even farther, finding new roughness and textures for his mineral series.

Philadelphia area artists in the exhibit include Lee, Henry, Klein, Bobrowicz, Manella, Orr, Leslie Grigsby, Diane Koppisch Hricko, Mi-Kyoung Lee, Nancy Middlebrook, Lewis Knauss, Kathryn Pannepacker, Leslie Pontz, Sophie Sanders, and Deborah Warner.

The show, which was curated by Snyderman Gallery Director Bruce Hoffman, will remain up through March 20.