The image of Latin America functioned for nineteenth-century North Americans much as that of the Middle East did for certain Europeans: as a screen on which to project their fantasies. In the case of the Western hemisphere, these were largely of a pre-lapsarian past. Roxana Pérez-Méndez has consistently explored the place of Puerto Rico within U.S. culture, and with her project, Este Es Mi Pais (This is My Homeland) at the Morris Gallery at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA, up through Sept. 26, 2010) she employs PAFA’s collections to explore the history of interactions within the Americas.

One enters the gallery through a gold-fringed, red velvet curtain pulled to the side. PAFA regulars and students of American art and museum history will recognize the reference to Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait, on view upstairs, in which he beckons the viewer into his museum. Peale’s interest in natural as well as human history preceded that of a number of American artists in the nineteenth century, most notably Frederick Church and Martin Johnson Heade. Following the much-publicized scientific explorations of Alexander von Humbolt, both artists made their own journeys in South America, bringing back images of flora and fauna which they incorporated into their work (the most striking example being Church’s monumental Heart of the Andes, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

On passing beyond Pérez-Méndez’s drape one sees a caged, domestic parakeet on which a video camera is focused; it conveys a live feed which is projected onto a hologram on the wall beyond. The hologram is fixed at approximately 45 degrees to the wall in front of James Peale’s charming portrait of Anna Maria Hodkinson. The portrait of 1800 shows a girl, aged about ten, holding a tropical parakeet (larger than those we’re familiar with). We see our own reflection as well as that of the caged bird in the glass, where they merge with the portrait behind. The South American bird has been transported, tamed, domesticated; it has become a child’s plaything and, no doubt, a sign of her family’s wealth.

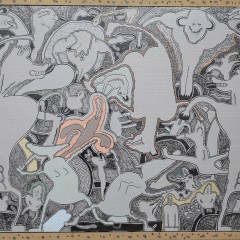

The case beyond it shows a bolt of off-white cloth onto which silhouettes have been printed in a very similar color. I was able to make out a group of figures and behind them a landscape, which curator Julien Robson helpfully identified as details from Benjamin West’s painting of Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. I don’t know whether the barely-discernible images indicate suppression of the historical memory of Penn’s shady dealing with the first Americans, or the fact that this initial treachery is the not quite blank background to all later history.

The first piece visible in the darkened room around the corner, Selva (Jungle) is a Wardian Case (or terrarium) filled with lush tropical plants, through which the image of a tiny wood nymph flits (looking rather like Tinkerbell in the animated film of Peter Pan), via the magic of the Pepper’s Ghost hologram. Throughout this room and the next Pérez-Méndez has culled paintings from PAFA’s collection that contain imagery of the inhabitants and landscape of Latin America and juxtaposed them with herself , the contemporary indigene, either parodying the image that others have created of her, or retreating into her unspoiled, native landscape.

A number of museums have asked artists to respond to their collections, and in Pérez-Méndez PAFA found an ideal match, an artist who shares the interest in the subjects of many of its works but approaches them from an entirely different direction. This exhibition is a particularly fruitful view, explicit about the artist’s investment in the subject, of a southwards extension to nineteenth-century American expansionism. Pérez-Méndez rebukes those artists who found an image of Eden in the tropical landscape, reminding them that they are not the first humans to walk there.

Anyone wanting to read about the nineteenth-century artists and their travels would do well to see Katherine Manthorne’s Tropical Renaissance; North American Artists Exploring Latin America, 1839-1879 (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).