Discussion of globalization in the art world most often addresses the situation of artists, the art market, and large international exhibitions, many of them held periodically such as Documenta or biennial exhibitions in Sao Paolo, Istanbul, Sharjah and elsewhere. There has been less general discussion about what globalization means for other art institutions, so I was interested to find the book, The Global Art World; Audiences, Markets, and Museums, edited by Hans Belting and Andrea Buddenseig (Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern:2009, ISBN 978-3-7757-2407-4), which is much less dry than its title.

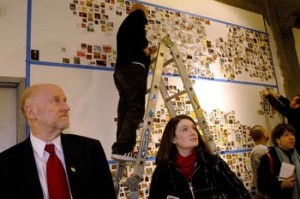

The essays are by a very international group, many of them participants in the conference Where is Art Contemporary? held at the ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, in 2007 as part of its Global Art Museum project. The first part of the book deals with the globalization of art and the new geography of art. But it’s the second part that particularly interests me; it addresses how museums across the globe are dealing with their own local audiences as well as with an increasingly globalized art world.

I was surprised that a number of essays describe situations that are very familiar to those of us involved with U.S. museums. Savas Arslan, a professor of film in Istanbul discusses private art museums in Istanbul, which have become the city’s major venues for the exhibition of contemporary art. While he discusses these private museums in the context of changing desires for leisure activities among the city’s urban middle classes, he might be describing Miami which last year had five, and by now may have six major private museums devoted to contemporary art (see Rubell Family Collection, above). Any one of them has a stronger collection than the region’s public museums. The Japanese sociologist Masakki Morishita talks about a longstanding controversy in Japanese regional museums about the tension between the curators, who want to exhibit a broad range of the best work possible, and the area’s artists, who claim that a publically-funded institution should exhibit the area’s artists. Despite the fact that U.S. museums are rarely publically funded, the same tension exists in every regional U.S. museum I know.

In an article on Museum Politics and Nationalism in Singapore, Eugene Tan, an art historian, critic and curator, discusses the impact on government policy of viewing the arts sector primarily for its economic potential: whether to promote cultural tourism, to attract foreign investment, or to establish a reputation of being a culturally vibrant area where business can flourish. In Singapore this has lead to government funding for a National Art Gallery based on the National Gallery, London. Tan doubts that such an imported model, and in a country with a tradition of centralized government censorship, is likely to have a positive impact on the country’s art production.

Tan’s description of the instrumental view of the arts sector as an economic generator sounded remarkably familiar; anyone who read about the new NEA Chairman, Rocco Landsman’s visit to Philadelphia in March will remember that the discussion focused on the importance of the arts to community and economic development. While I think the community development portion is likely correct, such influence doesn’t usually lead to the sort of neat indicators that funders like. As to economic development, a vibrant arts community certainly provides work for artists and art workers, who need jobs like everyone else, and for their suppliers and the real estate industry; their further economic impact is often based on fuzzy economics. I’ve always thought that the arts should receive public support because the public values them for themselves, their children and their community – not merely for attracting tourists and their money or attracting industries to a region. That is an honest justification which has more reasonable research to support it.