In the years since Eastern State Penitentiary began showing art, the Penitentiary itself has buffed up with audio tours, signage, rehabilitated spaces that look as good (or bad) as new, and enough safety so a hard-hat is no longer required to protect the heads of tourists from falling debris.

Even with all this spit and polish, the place is still a monument to entropy, with passages of peeling paint, crumbling and tumbling cement, and invading plants.

With the prison now a bona fide museum experience, the art installation program that used to be a terrific draw there now seems by in large beside the point. This year there are four new installations.

The highlight is Bill Morrison and Vijay Iyer’s Release, a video that manipulates recently discovered archival footage of the crowd outside the prison, awaiting Al Capone’s release in 1930. The video is nicely installed right next to Capone’s cell in the prison, which has been gussied up to recreate how the celebrity criminal was permitted to fix up his digs. That cult of celebrity is captured in the gawking crowd of the film, which also seems to allude to our our current daily intake of the celebrity sideshow, presented as news. The film demonstrates the seeds of the culture gone wrong, and it’s mesmerizing. Morrison worked the video, Iyer created the music, and independent curator Julie Courtney asked the two if they would collaborate. They said yes.

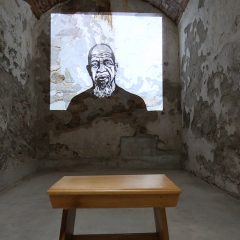

From Mary DeWitt’s Pardon Me, a series of portraits and recordings of women incarcerated at Pennsylvania’s State Correctional Institution at Muncy, the recording of prisoner Marie Scott stands out. Her anger and frustration is chilling, unexpected, and not especially sympathetic.

Sharyn O’Mara’s Victim Impact Statement is the flip side of the DeWitt portraits. O’Mara’s video installation shows the permanent impairments that affect a victim’s daily life–but the affect is clinically flat, the installation sanitary and tidy in the raw spaces of the penitentiary.

James Mills, for his On Tour, has installed a number of directional signs for macabre tourism sites, for instance a sign pointing to the MOVE bombing location on Osage Ave. But the sign doesn’t even point in the right direction, as far as I could figure. And why would Antietam, I wonder, be on Mills’ honor role of such sites? Is he saying we should remember only cheerful things? And therefore is he saying the prison’s history is best forgotten?

My memory of the first round of art installations in 1995 draws me back to see the new ones, year after year. But each year, the number of satisfying new installations diminishes. Fortunately some of the standing older installations–like Linda Brenner’s crowd-pleasing ghost cats– still give me some pleasure. I don’t really think the art program should cease. The space is still a tremendous opportunity. But it’s not so easy to rise beyond the power of the building.

The prison itself is a giant metaphor that tackles big issues like the limitations of human beings as social engineers, the effects of time, or the strength of human beings under duress, for example. Art that succeeds here has to go in a different direction in order to compete with and complement the building and its meanings. The Release video works partially because, while historically relevant, it also illuminates other big issues worth a think.