London, Kensington Gardens, August, Sunday, blue skies, warmish.

Just off the entrance to The Serpentine Gallery stands a temporary pavilion in hospital white. I approach the small building just as one of the last English heartbeats is recorded for posterity; that is, copied to a fat hard drive to be added to yet another fat hard drive then shipped to the uninhabited Japanese island of Teshima and digitally secured at the Benesse Art Site Naoshima…until Doomsday. This is the premise of the expanding and ongoing work of Christian Boltanski, Les Archives du Coeur, registering a rambling sample of the world’s pulse.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 1 Boltanski 2](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/Boltanski-2-300x225.jpg)

Charlotte Cooper, an English teenager who with her mother trained down from Bristol to have the sound of her heart recorded for all time, emerges with her dog Toffee (on a outfit-matching pink leash), tenderly holding the two-minute CD of her heart’s lively beat, (she’s no. 001449). Boltanski souvenir in hand, Charlotte and Mom Cooper chat with the amiable artist-musician-and-guy-who-looks-like-a-doctor-but-is-only-a-guide, Thomas Hawkins. Ms. Cooper is excited to have donated her young unbroken heartbeat to Boltanski’s project. “It didn’t hurt,” she says. “It was fun.” Hers is one of thousands.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 2 Boltanski](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/Boltanski-212x300.jpg)

Boltanski along with his artist wife, Annette Messager, pass for France’s aesthetic power couple. The artist maintains a studio near Paris in Malakoff, a self-styled communist suburb filled with old factory-turned-loft spaces, and easy access to the inside ring of Paris via Métro or side street. Arguably France’s most important artistic export after Yves Klein, Boltanski often wanders around my street, the rue Daguerre, window shopping, buying bread, enjoying a coffee on a café terrace, smoking his pipe and in general pretty quiet for such a famous guy. During these walks, the artist says, he gets his ideas. In the studio, he claims, he does nothing. Yet for more than 40 years, Boltanski has been quite busy mining the detritus of the world in a “career-long examination of the issues of death, memory, disappearance and loss,” according to The Serpentine Gallery press release. Most recently, these examinations have involved tons and tons of clothes.

The Serpentine Gallery installation, however, has no clothes, unlike his exhibitions in Paris, New York and Milan; Boltanski’s effort in London was designed solely to gather heartbeats, like a mushroom picker in an English garden.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 3 C Bol](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/C-Bol-201x300.jpg)

In June 1992 when I flew up to Montreal from New York to participate as an art writer person in the opening of the new Contemporary Art Museum. I sat next to a man I was certain was the artist Leon Golub. I was too timid to start a conversation with Mr. Golub, besides punching out poetic jewels like “Excuse me … bumpy ride … hey, we’re here.” It wasn’t the American painter Leon Golub (1922-2004), I learned 10 years after I’d moved to Paris.

A few times I’ve sat with him at in a café, and it was one of those times, Boltanski told me that indeed he was on that plane jetting to Montreal. We had a nice laugh about that and I tried to account for their facial similarities but it made little difference. He enjoyed the case of mistaken identity. Then, about two years ago while walking towards Montparnasse from my studio, I heard a grumbling sound behind me, growing louder and louder. Whoa! A greenish Volkswagen was bearing down on me. My heart skipped a beat. “Hey!” I shouted at the driver, as I skittered out of the way. It was Boltanski. He laughed, gave that French shrug, waved and motored on. Art performance? No, Christian Boltanski doesn’t run over American artists in Paris, no matter how quaint that idea might be.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 4 BoltanskiArmory](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/BoltanskiArmory-300x199.jpg)

What Boltanski does do is collect. He’s a collector par excellence, or better, an archivist on an ambitious and wonderfully absurd quest. Born in Paris in 1944, Boltanski has spent most of his adult life growing his installations into ever more enormous monuments of memory and loss. You had to be in a coma to miss the installation shots this past January of “Personne” (Nobody), the Monumenta exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris. For this, Boltanski assembled piles and piles of used clothing in a tremendous grid on the floor, a poetic field intimating death, absurdity and anonymity. Worn out pants, ratty sweaters, kids’ t-shirts, out-of-fashion skirts and boots are laid out, as one writer said, “flower beds.” Or, let’s say, grave sites. Clothes were lifted and dropped repeatedly, day in and day out, from a crane to the pounding mix of 15,000 heartbeats. Something Sisyphus could appreciate.

Read Max Mulhern’s artblog review of “Personne,”– Boltanski People – published on January 16, 2010.

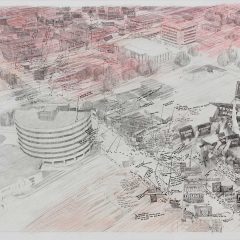

This installation was repeated in New York’s Armory in May in a more spectacular display entitled “No Man’s Land.” This time, Boltanski employed a five-story crane to lift and then drop the used clothing onto a 25-foot pile. In these exhibitions, Boltanski set up the Archives du Coeur as an ongoing heartbeat-gathering laboratory, but also as a counterpoint to the big bass sound of emptiness moaning from the hollow of these immense spaces. In New York, as in Paris, the heartbeats played in a pounding harmony of thousands.

While some may dismiss as slight or simpleminded, these large displays of tossed clothing roaming the world’s art spaces (Boltanski reprised this symphony of heartbeats and old clothes in Milan’s Hangar Bicocca Contemporary Art Museum) – and one can easily imagine comments like, “What is this a some new kind of French laundry?” – it impossible not to be moved by Boltanski’s vision, which is precise and all-encompassing even if it spills over across the floor. His is an art that touches an individual from afar – like a storm cloud – and from up close, like the pinch of a syringe. But instead of medical devices, he employs memory in the form of your father’s well-worn sport coat or your mother’s kitchen apron or your brother’s torn blue jeans – or your living heartbeat.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 5 Boltanski Italy](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/Boltanski-Italy-300x199.jpg)

For some 40 years Christian Boltanski has arranged tin biscuit boxes, yellowed identity photographs, and now giant piles of Salvation Army discards into archives, presented in profoundly absorbing walk-through installations in order to examine, present and document the exacting sense of loss this world offers through the objects we use and to some extent, fetishize. It’s a personal project on many levels; it would have to be. One can only surmise that these works constitute the artist’s own deep confrontation of the consciousness of death.

I remember back in 1992 speaking with Rachel Stella (daughter of Barbara Rose and Frank Stella, currently director of Stellar Graphics), at her gallery/loft in Paris’s 16th arrondisement. We talked about a number of artists and Boltanski’s 1990 work, “Les Suisses morts” (The Dead Swiss), came up. Here the artist used photographs from from Swiss obituaries in an installation; photographs the family had chosen to publish – smiling studio shots, candids, graduation poses. The installation was funerary with the images affixed to a wall of tin boxes, and others, enlarged slightly larger than life beyond the wall of tins, were strung up of head shots of now-forgotten Swiss people; memorialized shadows of once very real lives.

Ms. Stella was furious, calling it a terrible violation of someone’s privacy. I was more shocked by her attack than I was by the artist’s work, but it stuck with me. Death and art, are of course, old friends; indeed what would one be without the other? And now when I walk through the Montparnasse cemetery, where hundreds of France’s literary and artist greats endure the great sleep, I half imagine it all to be a Boltanski installation. Parisians and tourists wander through with their maps of the famous dead buried here, placing stones on the graves of Jean-Paul Sarte and Simone de Beauvoir or Métro tickets on Serge Gainsbourg in a similar fashion as those visiting a Boltanski exhibition – with reverence, melancholy and a wistful smile. You end up listening to your own heartbeat race in the presence this death. Wars and hospitals no doubt engender similar reactions.

![Under An English Sky [Part II] : Christian Boltanski's Les Archives Du Coeur At The Serpentine Gallery 6 BOLTANSKI Christian Les Suisses morts044](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/BOLTANSKI__Christian__Les_Suisses_morts044-300x216.jpg)

While Boltanski began his career in the 1960s as a painter – he says he still paints – his signature works are clearly these Mount Rushmore-sized installations. No, the installations aren’t amusement parks, but rather specific and sober experiences, like a cold bath and no towel. The undertakings are beautiful and breathtaking, and engagingly sad. There is a touch of the preposterous in it all as well, but Boltanski’s sweeping irony is apparent, too: his own dress rehearsal for death.

As I take leave of Les Archives du Coeur, I’m thinking that this is really all about something quite simple: eternal heartbreak.

[1] One should note that the word, “record” derives from the Latin (and thus Old French), recordari, based on cor, cord- “heart.” Remember by heart, commit to memory. The noun was earliest used in law to denote the fact of being written down as evidence.

Serpentine Gallery, June 26 – August 8, 2010.

http://www.serpentinegallery.org/

Kensington Gardens, London W2 3XA

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer based in Paris. His next exhibition, Scared But Fresh, opens at The Orange Dot Gallery in London. His prints are available at Keep Calm Gallery.