Post by Cheryl Harper

What makes an artist’s vision so clear to himself early in life? The current exhibition of Yves Klein’s works at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington poses an answer by shedding light on the work of an artist whose work and manner is difficult to understand out of context.

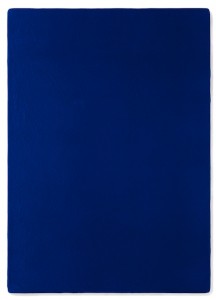

Klein’s ideas included taking ownership of one of the four elements — air — which included the sky. He also believed in directing others to make his work during performances rather than physically executing it himself. He patented a color already in existence by naming it International Klein Blue. Klein presaged much of the bravado and self promotion that are common among artists today. The artist’s concepts were as original as Duchamp’s or Dali’s, both of whom influenced his approach to art making. Like Duchamp, Klein found it harder to justify making objects as he progressed; like Dali, he found theatrical behavior instrumental in getting out his message. In addition to documenting his methods, Klein was an early practitioner of performance art, even planning his wedding as an art event.

Klein’s personality and the milieu of the French Avant Garde of the late 50s and early 60s come into focus through objects, correspondence, and video on display. There’s a 30- minute video that’s well worth watching, located just outside the exhibition in the adjacent inner concentric gallery. One nice aspect of the video presentations in the show is that you don’t have to leave the gallery for separate dark, curtained spaces.

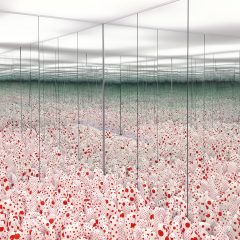

Throughout the exhibition, the viewer is aware of Klein’s patented pigment International Klein Blue (IKB) applied using a variety of methods: rollers, sponges, bodies, and as raw pigment. The well-known body paintings are represented as paintings on the wall but also in video documentation, in which you see nude women of varying heights — exquisitely proportioned and cosmetically perfect (clothing is unthinkable) — rub themselves with IKB paint and roll around on canvases on the floor and wall transferring paint to the canvas with their motions. Klein literally played the maestro; conducting the models and a chamber orchestra while impeccably dressed, with no splatters reaching him. He is the opposite of Pollack’s very physical approach. His controlled physicality developed from his expertise as a young Judo master; he spent 15 months in Japan sponsored by a family patron, perfecting his body/mind connection before he concentrated solely on art. (See “Yves Klein and the Blue of Distance” by Rebecca Solnit, New England Review. Middlebury: 2005 Vol 26, Issue 2)

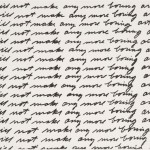

The title of the show comes from a gallery guestbook entry left by the Existentialist Albert Camus at a Klein exhibition in 1958 — With the Void, Full Powers. Klein embraced the comment, incorporating it into a title of a staged photo in his one day broadsheet sold on newsstands on November 27, 1960. The reader paid 35 newfrancs — the usual price for the Sunday paper. The broadsheet looked exactly like a Sunday journal; the unsuspecting newsstand purchaser expected the ususal paper only to find it exclusively extolling the genius of the artist/publisher. A reprint is available free in the gallery.

Born in Nice in 1928, Yves Klein died in June 1962, a month after suffering an initial heart attack during the Cannes Film Festival debut of a documentary film including his work. He had fully cooperated with the movie’s director only to witness in the final cut an expose on his narcissism, not his genius. According to the show’s video, Klein was overcome with this betrayal. Klein took advantage of every waking hour, likely having more of them than the average person as he abused legal amphetamines; most likely his fatal heart attack was inevitable. (Again, see Rebecca Solnit for more.)

This exhibition is the first retrospective in the United States of Klein’s work since 1982 at the Guggenheim Museum. Guides specifically trained for the show were in the galleries the day I attended it. The videos, archival material (letters, notes, and drawings) are interspersed throughout the show adding clarity to this story of this sophisticated and complicated artist. Klein’s work was critical to the foundation of American Pop Art and Performance art in the 60s. His close friends, Arman and Tinguely, brought his ideas to New York where they were catalysts between the ideas of New Realism (of which they and Klein were founders) to Pop Art. Klein worked in multiple styles simultaneously and seeing them side by side gives the viewer an appreciation of his prodigious and original oeuvre. If you can’t make it to the show, a new catalog was produced by the Hirshhorn Museum. In additon, there is a comprehensive archive devoted to the artist.

“Yves Klein: With the Void, Full Powers,” on view at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, through Sept. 12, 2010