In the midst of election season, an exhibition exploring the use of American vernacular imagery and style is particularly apt. The interest in folk art, as with folk tales, is historically associated with nationalism and the search for originary stories that always involve a lot of white-washing, if not outright fictions. In the U.S. the far right is always ready to raise the flag and other symbols associated with 19th century, white, agrarian society – the real America. Americanana, organized by Katy Siegel for the Bertha and Karl Leubsdorf Art Gallery, Hunter college (through Dec. 4, 2010) includes thirteen artists who have taken on aspects of the vernacular in a spirit closer to that of People for the American Way, making use of its rhetoric for more complex ends.

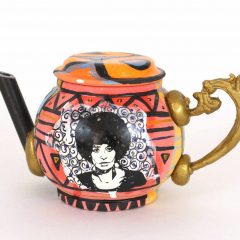

The hiccup of the title’s last syllable is not a negation- Americana? Na! – rather a neologism expressing things that are typical of or concerned with Americana. What’s fascinating is the range of artists who share that concern. The first work on view is Jasper Johns’ lithograph, Two Flags (1980); these are flags with their own agenda: as found imagery, as pretext for consummately-beautiful mark-making, as images representing objects which represent ideas. Faith Ringold’s Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1980) reclaims the patchwork quilt as an African American art form, associated with the creative recycling of the poor and with African roots. She also reclaims Jemima as a real woman with her own life story, rather than the stereotyped black woman as eternal source of nurture for her oppressors.

In describing his two Dustpans ( Douglas Fir and Amaranth, both 1972) , H.C. Westerman said I made each one of these by hand and by that I mean I did not subcontract them to a factory or pay some guy to make them for me. He emphatically returned to handmade production of vernacular objects as a riposte to Duchamp’s appropriation of everyday, commercial objects as readymades and to the outsourced fabrication of much Minimalist sculpture. It was surprising, then, to see them looking so appropriate beside Donald Judd’s Chair (designed 1991, fabricated 2002) made of knotty Texas pine. If I thought Judd had a sense of humor (something no one accused him of), I’d say he was joking – producing a chair whose form derives from the severe geometry of Rietveld in a material associated with middle-class American dens and rec rooms. Judd put on a vernacular voice in his writing (an editor, rejecting his reviews, described their style as shambling basic-Hemingway), but that doesn’t account for the clash of the chair’s material and form.

Mel Edwards’ four pieces from his Lynch Fragments series demonstrate his own transformation of swords into plowshares. He takes various bits of steel equated with racial violence and destruction (chains, hooks, crow bars, axes) and turns them into masks of resistance. These are important pieces of trenchantly biting restraint, and too little known.

Americanana is a small but intelligently-focused exhibition; it presents an unexpected grouping of artists around a theme which expands the way we generally think about them. It’s the sort of thoughtful grouping I’d like to see more of, rather than endless, monographic exhibitions, and is well worth the trip to E. 68th Street. The other artists include Robert Gober, Josephine Halvorson, Phillip Hefferton, Allan McCollum, Elaine Reichek, James Turrell (with Nicholas Mosse and Bill Burke) and Kara Walker.