Fiona Tan explores storytelling, memory, and the part they play in the formation of identity throughout this exhibition of five video installations, various associated sketches and one single-channel video. Rise and Fall (2009), elongated projections onto two large, side-by-side screens, is a wordless meditation, set to music, of a woman no longer young but still conscious of her looks; she was clearly a beauty in her youth.

As the video proceeds we gather that the young woman pictured on the second screen is the memory of her younger self. They often move through domestic activities (sleeping, bathing, dressing) in parallel; this is inter-cut with scenes of violently rushing water (shot at Niagra Falls, it turns out). It’s a hackneyed metaphor – the water’s endless surging as an image of time’s relentless uni-directionality – but in Tan’s hands that doesn’t seem to matter; she creates extraordinarily emotional work out of simple stories and well-worn themes. This is true of all of her work; it’s achieved with such skill and restraint that the limitations of her material never bother us, but echo enough of our own thoughts that we are carried away by them.

The large, single screen installation of A Lapse of Memory (2007) shows the often puzzling and slightly obsessive, daily routines of a man who, we’re told, is losing his memory; it is set, inexplicably, in the lush but abandoned Georgian Chinoiserie of the Brighton Pavillion. The narrator offers conflicting stories of the aging man who, forgetting his past, can neither confirm or reject them. Henry is waiting for a story he can make his home. The video posits memory as essential to the construction of self, and Henry (or Eng Lee, the protagonist of the alternative narrative), unable to retain his own story, may be losing himself to tales told by others.

In 2008 Tan was invited by the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, to explore the collections; Provenance is the resulting work. The six small, black and white, slowly-moving portraits are of people the artist knows, although they are not identified on the museum’s label. Their movement makes real the simile that good portraiture brings the sitter to life; yet they move slowly enough to suit portraiture’s observational requirements rather than the more usual pace of video geared to narrative. Shown as a 6-channel installation, each is framed to a vertical format with proportions common to portrait painting or photographs, but startling for video. Tan clearly studied more than 17th century portraiture; her sitters are each shown within an environment, which the camera pans, sometimes resting on still lives reminiscent of those Tan would have seen in the museum, at others showing rooms seen through doors in the manner of De Hooch and others. If I don’t entirely understand the title (provenance is the term art historians use to describe an artwork’s history of ownership and/or display), perhaps it is clarified in the artist’s book made to accompany the installation. I can only surmise that Tan is suggesting her sitters are products of individual histories, reflected in the objects they assemble around them.

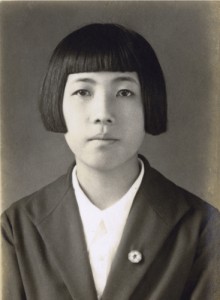

The found imagery which Tan used in much of her earlier work appears in the two channel installation, The Changeling (2006). Tan uses an album of class photographs of Japanese schoolgirls from the early 20th century. On one side of the room is the image of a single girl, while opposite it, a long sequence of identically-dressed and similarly-coiffed schoolgirls meld into one another. The voice-over is a flowing internal dialog in which the narrator imagines one or another image as herself, her mother, her grandmother. It explores the use of photographs to tell of the past and to fix images in memory; or possibly to support invented stories.

The hour-long video, May You Live in Interesting Times (the title is an old Chinese curse) was made for Dutch television in 1997. While thoroughly well made, it’s the sort of exploration of identity via tracing an immigrant lineage that is familiar from U.S. Public Television: travel to visit relatives, each of whom has a different version of the family story, the attempt to separate an inherited identity from that provided by personal history and circumstance. I suspect that the U.S. is so full of people of mixed heritage and complicated histories of exile that the story is hardly novel here. What is striking, throughout her work, is Tan’s consistent perspective that identity is internally-generated, rather that a reflection of outsiders’ expectations.

The exhibition, organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, which along with the Freer constitute the Smithsonian’s Museums of Asian Art, through Jan. 16, 2011. While the Sackler has exhibited very interesting video for some time, this exhibition is a major expansion of its involvement with contemporary art. It’s a very welcome addition to Washington’s contemporary art scene.