Beaten almost to death by thugs in 2000 and left with permanent brain damage, Mark Hogancamp’s post-recovery story, told in the new documentary movie Marwencol, is a survivor’s tale in which art plays a pivotal role. The movie is a great, empathetic look at the microcosm of Hogancamp’s life. He’s an odd duck to be sure, but very talented, and, miraculously, a survivor.

Hogancamp had artistic talent before the attack — the movie shows you some of his intricate and well-done figure drawings. But he was also an alcoholic, which he proclaims in the movie again and again. (He now feels no alcoholic urges and does not drink.) After the attack he was left with little memory of his previous life and with massive deficits requiring speech therapy and physical therapies to regain his small and large motor functions. That art becomes his path to recovery is in some ways to be expected. It’s what he produces that is the surprise.

Marwencol is Hogancamp’s name for a tiny World War II-era European town that he created in his backyard. Marwencol stands for MarkWendyColleen (Mark and two of his good friends). The little town is made out of scrap wood and other discards and it is the backdrop for fantasy battles and love stories enacted by realistic, 1/6 scale dolls that Hogancamp purchases from specialty doll sellers. The dolls, which look like Barbie and Ken — although not smiling and with even more bendable joints — The dolls represent the alter-egos of Mark, his friends and the enemies that are constantly out to get him.

Several years back Mark began photographing the town’s dramas in cinematic close-ups that came to the attention of Esopus magazine, which published a selection of them (Esopus Space gallery just closed an exhibit of the photos). Four years ago, after seeing the photo spread, film-maker Jeff Malmberg began making this documentary about Hogancamp and his town.

The film shows Hogancamp as he makes new props, dresses and positions his dolls for action, and photographs them. The film interviews Mark’s co-workers at the restaurant in Kingston, NY, where Mark works in the kitchen (he makes the meatballs and mops up). Mark talks about the assault on him; about being an alcoholic; about his long recovery. He is a solitary soul, highly introspective and anxious. If the movie has a catharsis, it’s watching Mark work through his anxiety about a then-upcoming show at White Columns. For this man, who does not call himself an artist, and who is chary of the world outside the safety of his backyard, the White Columns show is a huge crisis of confidence.

Marwencol the town is art and therapy, and in spirit it very much resembles the epic creations of other outsider or self-taught artists like Henry Darger and Eugene von Bruenchenhein. Marwencol’s story is about life and death, love and hate, heroes and villains. And it shares the hermetically sealed quality of much outsider art.

Marwencol the movie, at 83 minutes long and in full color, has great empathy for Mark Hogancamp. The film is hardly exploitative, but it does raise issues of exploitation of vulnerable people who get dragged, cajoled or somehow spirited into the limelight. (The Maysles film Grey Gardens is a point of comparison here). Hogancamp is a very private person, with a secret (see the movie for more). He’s very anxious about revealing himself to the world. His anxiety about the White Columns show — which is documented all the way up to and including that show’s opening — makes you understand the man’s reluctance. He is so entwined with his fictions that for him to speak about the photos as photos is almost impossible. At the opening, a young couple asks him questions about the photos and he speaks about the stories and about himself. Marwencol is him and his world–autobiographical and personal.

My question about the movie is about the level of trust between filmmakers in general and their subjects. Did Hogancamp truly understand the complete unveiling of himself and Marwencol that would take place in this movie? Hogancamp is very relaxed in front of the video cameras. He talks to the camera as if he’s speaking with a dear friend. It’s very intimate and self-revelatory. Contrasting this with his sleepless-night-anxiety about the White Columns show and you have to wonder. Somewhere in the movie-making, trust became friendship. Mark considers the filmmaker a friend and created a doll for him in Marwencol village. But is this really friendship? Maybe — I don’t know.

The movie is well worth a view — it raises all kinds of issues. It opens at the Ritz at the Bourse on Nov. 19 for one week only (I saw a screener on my computer).

11/19–ritz theatres

MARWENCOL (Cinema Guild)

NR, 83 min

Directed by Jeff Malmberg

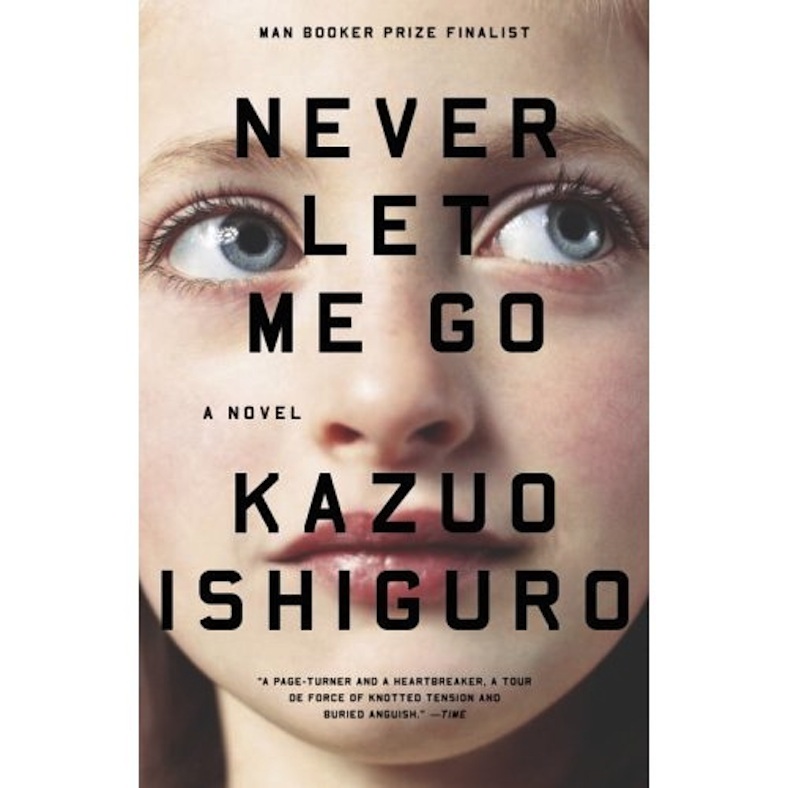

Never Let Me Go, the movie, is in circulation in theaters. I just read the 2005 book by Kazuo Ishiguro (haven’t seen the movie). Like Marwencol, NLMG has art as a serious part of a story that deals with exploited and damaged humans. (Spoiler Alert–skip the rest of this if you want to see the movie or read the book without too much info).

The young humans in NLMG, students at Hailsham school — a Hogwarts-like creepy boarding school for children from around 5-16 — are encouraged, nay required to make art–a ton of it, in all media. They trade their art at art exchanges held at the school, and the best work is selected by a mysterious woman known as Madame who whisks it away for what the students believe to be her gallery. Some students think making good art will help them climb up out of their government-dictated futures, and if you don’t participate in art-making, as one student doesn’t, you are shunned. In the microcosm of the school, art is big. But ultimately, in the real world, the art is meaningless. It doesn’t help (or hinder) the students. Since the creation of prized art gives the students false hope, though, art can be seen as a tool of the establishment for submission and compliance.

It must be said that science is the biggest evil in this book. In fact, science is the ruler and chief exploiter, with art only one tool. Ishiguro could have used sports as the devious tool instead of art in his story. (Sports is already a contemporary villain for many — see recent concussion reports). And while this book doesn’t suggest art itself is evil (the students get much personal enjoyment from making it and sharing it and even the one hold-out begins making art towards the end). It does seem to be a cautionary tale in which belief in something ephemeral (art) coupled with a lack of information and general dis-empowerment is a recipe for tragedy.