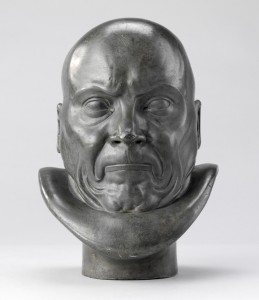

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783: From Neoclassicism to Expressionism at the Neue Galerie, through Jan. 10, 2011 (before showing at the Louvre, Jan. 26-April 25) is a must see for anyone interested in art who is not likely to get to the Belvedere in Vienna, where the only significant body of his sculpture can be seen. Messerschmidt ‘s most significant work, known as the Character Heads, was a group of more than sixty variants, and it makes a huge difference to see a number of them together.

Messerschmidt’s Character Heads exist outside the history of art. While the artist and his work have been the subject of endless speculation, the most interesting questions – why he made them and what he meant by them – are unlikely to be answered. Perhaps this explains why he is probably the most-studied artist who remains outside the traditional canon; explanations for his work can never be disproved.

The artist was born in 1736 to a family of sculptors in Bavaria, and completed his education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. There he quickly established a reputation, and in 1764 was commissioned to produce a portrait of the Empress Maria Theresa. Messerschmidt spent several months in Rome in 1765 and returned to become the most important sculptor of his generation in Vienna, with teaching positions at both of the city’s art academies.

Something happened in 1771; Messerschmidt stopped receiving commissions and began the Character Heads; the group designation as well as the names of the individual heads are posthumous, and foolish, but used by convention. In 1774 he was rejected for a permanent appointment at the Academy of Fine Arts. The faculty didn’t question his talent, but his mental state; there is also speculation that he was caught up in academic politics. Messerschmidt retreated first to Munich, then to Bratislava where he received the occasional portrait commission and produced alabaster medallions, but primarily worked on the heads. They numbered more than sixty (although only about forty survive); most were cast in lead or lead alloys, the rest in alabaster.

Messerschmidt died at 47 and the first exhibition of the heads was ten years later, when they received names by which they are still identified. Numerous scholars, beginning with Ernst Kris in 1932, have attempted posthumous psychiatric diagnoses and many have seen the Character Heads as manifestations of the artist’s mental illness. The only extended, lifetime description of the artist’s behavior comes from the writer Friederich Nicolai, who visited Messerschmidt in 1761 and described his common life rather inclining to eccentricity…. According to Nicolai, the artist was plagued with spirits at night and physical pains during the days. He spoke incoherently about the significance of proportions and a Spirit of Proportions; the heads were intended to protect him from the spirits.

Mad or not? We will never know; but two aspects of the artist’s biography are certainly of major significance to his art. The first is his trip to Rome. With some time lag, his work changed significantly following his return to Vienna. His portrait busts, which had reflected the last gasp of Baroque elegance, became Roman. His was not the Neoclassicism of Houdon, whose sculpture suggested a sense of life and the softness of flesh, or of sculptors such as Canova, who created cool, idealized forms and Antique details. Messerschmidt produced the closest approximation of the austerity of Imperial Roman portraiture – those rows of ancestor busts which would have been assembled at home. There is nothing of the period quite like them, and it is striking that his patrons, who included minor Central European princes, were so willing to accept his new style.

The other point of crucial significance is that Messerschmidt created the Character Heads for himself; I can think of no other significant, professionally-trained artist who produced his most important work with regard to neither patrons nor public until Van Gogh; and while Van Gogh’s situation has taken over the popular imagination, it has no relationship to art production prior to the late 19th century and the concept of an avant garde. Messerschmidt believed the heads were important and hoped to exhibit them, but he was their primary audience. This is what situates the Character Heads beyond art history.

Nicolai recorded that the artist would pinch himself and make faces in front of a mirror, but the Character Heads also betray his deep knowledge of anatomy and aspects of the head he could not have seen in the mirror: the indentation at the back of the skull where it meets the neck, the changes to neck and chin in profile, during a grimace, or the wrinkles beneath the chin when tucked in. They are also somewhat abstracted from actual facial expressions, some exaggerated to the point of caricature, and tend towards an ideal symmetry rarely found in life.

The Character Heads strike me not as realistic representations of the way a face changes with emotion, but as attempts to represent the way emotions, and those actions expressed through the face, feel from within. This is particularly clear with The Yawner; a yawn has both duration and occasional pauses, and when yawning one is very conscious of muscles tensing, then releasing. Messerschmidt captures that muscular self-consciousness. Some scholars have discussed the heads in terms of prior studies of facial expressions, such as Le Brun’s famous treatise, and to late 18th century interest in physiognomy; but Le Brun established an alphabet of standardized expressions that could be used by his followers, and Lavater and others were interested in the typical. These bear no relation to Messerschmidt’s project.

The Character Heads are realized with such extraordinary conviction and skill that their effect transcends their unknowable origins. They are hauntingly powerful visions, wrenched from the gut. After a century when they circulated outside art venues, they were welcomed to Vienna finally prepared for their emotional tension and ambiguity by the studies of Freud and his colleagues. They have been of great interest to artists, which is one reason they are on view at a museum dedicated to Austrian and German art of the early 20th century. The Louvre, Getty and Metropolitan Museums have each purchased one of the Character Heads during the last ten years, but the opportunity to see such a grouping along with Messerschmidt’s striking earlier portraits is unlikely to be repeated. Don’t pass it up.