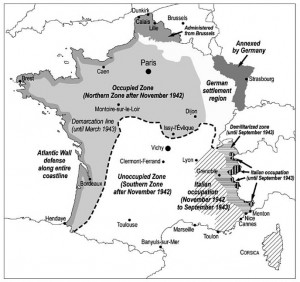

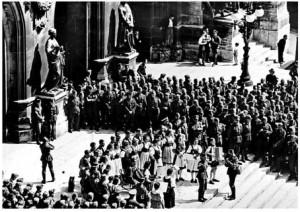

When the Nazi army rolled over Paris in late spring, 1940, and occupied the city on June 14, 1940, one might say the lights went out in the world’s greatest cultural beacon. But the truth is more complex, morally and aesthetically, as artists, performers, writers and others in the Paris culture industry either co-existed or collaborated outright with the occupiers. Artists and intellectuals “survived” the war in a fashion, and others, particularly in cinema, enjoyed a “good war.” Sartre famously burnished his war credentials after the Occupation; Picasso was largely selfish and unpolitical; painters Derain and Vlaminck traveled as visiting artists to Germany during the war years; Céline embraced the new destruction along with other French artists who were inspired by the anti-Semitic Nazi occupiers. French culture, seen as fragile under the Occupation, was more of a strange political brew, but there is no doubt that Parisian theaters, music halls and cinemas continued to entertain, and Paris became the premiere vacation destination for the Nazi empire.

Paris during the Nazi Occupation is the vast subject Alan Riding takes on with a minesweeper’s verve. The former European cultural editor for The New York Times recounts in vivid detail the rich history of this errant half decade in And The Show Went On, (Knopf, 2010) laying out how the Nazis rolled over France and how France’s cultural institutions literally played on, staging shows and singing songs and painting pictures. The author argues in this 400-page history that the pre-war French art industry managed the morally impossible middle ground surprisingly well, and that the artists of the Occupation and their murky history of existence and collaboration during wartime is as we might expect: Conflicted. Following is an interview with Alan Riding that took place in Paris via e-mail over the last week of 2010.

On June 14, 1940, the Nazis effectively rolled over Paris and thus began, you write, the city’s “worst political moment of the 20th century.” Was it also, in your estimation, the beginning of the end of French dominance of the global aesthetics industry? Wasn’t it almost just after the war that Pollack, de Kooning, Gorky and other Ab Ex painters were “exported” to a global audience? All the Surrealists had left Paris for New York and of course without full access to the press, disseminating French (or European art) was nearly impossible.

I am struck by your phrase “global aesthetics industry” because, when it comes to looking beautiful, the French still have a pretty firm grip on the luxury goods, fashion and frills business. But in the visual arts above all, the occupation permanently undermined Paris’s position as the cradle of artistic creativity and, as you point out, by the mid-1940s the vanguard had moved to New York. Most of the great post-war names on French art scene were already great pre-war names, giants like Matisse and Picasso but also many others like Dufy and Derain and even Chagall, who returned to Paris after fleeing the occupation in 1941. But few French artists who emerged after the liberation came to rank as household names. Even the Surrealists, who in the main followed André Breton to New York in 1941, never recovered the power they had enjoyed in France or beyond in the 1920s and 1930s. So why did New York take over from Paris? Well, it had money and collectors and crucially it also had art dealers. And post-war Paris had none of the three.

When you write about an artist’s moral responsibility, you touch upon both talent and status. During the occupation, one assumes the greater artist (more talent, more wealth, higher stature) would seem to have more responsibility. But is this true? Not many artists swim in the deep moral waters of any age, so why should these French and émigré artists have acted any differently, that is other than your basic, terrified neighbor during wartime?

Well, the premise of my book is that artists, writers and intellectuals – what one might call “cultural celebrities” – do have special responsibilities in times of trouble just as they enjoy special privileges during the good times. Why should that be asked of them since they are likely to be as brave or cowardly as anyone else? The reason is that in many countries, certainly France and many other Latin countries, people expect artists and writers to be more thoughtful, perhaps more intelligent, probably more independent than the rest of us. If someone is famous for possessing some creative or artistic talent, he or she is somehow regarded as spiritually superior.

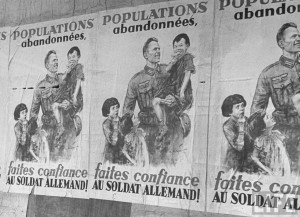

Even in the US, where the notion of the “intellectual” is viewed with suspicion, public opinion is open to be swayed today by famous actors or pop singers who take public positions on, say, famine in Africa or violence in Darfur or even global warming. Of course, during the occupation of France, it was a bit one-sided: the artists and writers who were most visible were those who showed sympathy for or willingness to collaborate with the Germans or their puppet Vichy regime, while those who opposed the occupiers struggled to be heard through clandestine newspapers and the like. So the example being given to the public at large was invariably a bad one. But it is worth recalling that, after the liberation, artists and writers who collaborated were often punished more than “ordinary” citizens specifically because they were perceived to have had special responsibilities. Between heroes and collaborators, of course, there were also many artists who simply tried to make ends meet, which meant performing before German audiences but not being seen socializing with the occupier. Still, one fact cannot be denied: among non-Jewish artists and creators, those who refused to paint, compose, write, publish or perform during the occupation can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Picasso famously stayed in Paris during the Occupation. Do you think it was Picasso’s stature that made him fearless and invulnerable to Nazi threats? Clearly Picasso wasn’t a political artist, but Guernica is of course one of the great political artworks of the 20th century. How do you see Picasso standing out from other painters at this time? Did the war years, for example, enhance his reputation? When, during a visit from Nazi soldiers questioned him about Guernica (1937), “Did you do this?” the artist, replied, “No, you did.” True story?

Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s mistress from late in the occupation, insisted to me that the Guernica story was true. Beyond that, I have no way of knowing, though it does seem like the kind of remark that the self-confident Spaniard might have made. On the other hand, as a Spaniard and an outspoken critic of General Franco, he was also vulnerable since Franco’s idea of neutrality placed him very close to Hitler. But perhaps even the Germans might have thought twice about interning the world’s most famous artist. Picasso himself was not a trouble-maker during the occupation: he continued to work in his Left Bank studio, was visited occasionally by German officers (including the writer Ernst Jünger), ate in neighborhood restaurants and was visited by his mistresses, Dora Maar and Marie-Thérèse Walter (until Ms. Gilot came along).

Perhaps what distinguished him most was that, unlike Matisse and many of his contemporaries, he remained in Paris and, in a sense, his very presence was an act of defiance. But, nothwithstanding Guernica, he was never a political artist as such and, even after he joined the French Communist Party after the liberation, he was hardly one to follow orders from Moscow-line apparatchiks. In fact, in the end, I think that Picasso’s reputation was barely touched by either the occupation or his membership of the Communist Party. Today, with endless exhibitions still keeping Picasso in the public eye, neither of these periods is more than very occasionally mentioned.

You write that artists of all flavors moved to Paris to escape the confines of their native Catholicism and traditional norms in order to peel apart their potential and change the world. French filmmakers, however, at first welcomed these actors, writers, doers but because they were slowly being crushed by Hollywood in the 1930s, sought some leverage and funds. The Germans provided it, and a collaboration ensued. Because cinema was a powerful, new art, with the potential to spread both images and sound, and therefore ideas as well as current events (or propaganda) in the newsreels, how do you assess the French filmmakers on this score? Are they more “guilty” than others in collaborating with the Nazis?

French filmmakers generally had a “good” war, not least because the exclusion and departure of Jewish producers, directors and screenwriters left them more room. And soon they also had no competition from British or American films. Add to this, the Nazis, notably Goebbels, wanted the French to be distracted as much as possible – and movies could do a good job at that. Indeed, Goebbels even sent a German producer, Alfred Greven, to Paris to found his own studio, Continental Films, to make French movies.

The question that arose after the liberation was whether making an apolitical “entertainment” movie during the occupation comprised collaboration. Well, it transpired that, except for Jean Renoir and a handful of others who left for the US, everyone else among non-Jews continued working, which meant accepting German censorship of screenplays, casts, director and even technicians. So it was difficult for some who worked to condemn others who also worked. There was a small resistance group within the industry – portrayed in Bertrand Tavernier’s film, Laissez-Passer – but its impact was minimal.

The Occupation did not arrive in Paris without collaboration, you write, implying that no conquering army could come into a country, take it over without insider help. What shocked you most about some of the artists – people we would assume to be morally courageous against the Nazi regime and fight it – who not only fell in line with the Nazis, but advanced their cause?

I think I was most struck by how blind ideological faith – in this case, in fascism and even National Socialism – led some French writers actually to celebrate Hitler’s crushing of “corrupt” and “decadent” France. For them, France’s defeat proved them right: parliamentary democracy and socialism were destroying France; now the country could be rebuilt from scratch. In a way, these writers – men like Robert Brasillach and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle – were not collaborators seeking some advantage for themselves; they were true believers. One other thing struck me forcefully, even if I was not exactly shocked: it was the vanity and narcissism of some artists, writers and performers who needed to be in the limelight – even if Nazi officers and soldiers were the ones applauding them. Among visual artists, for instance, why on earth did the likes of Derain, Vlaminck and van Dongen accept invitations from Goebbels to visit the Third Reich? The answer has to be that Goebbels made them feel important.

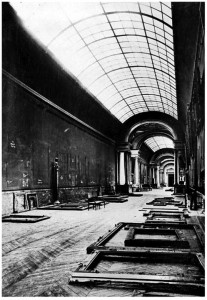

The Louvre was emptied out of its paintings, and yet many museums were looted by the Nazis. What kind of operation was the preservation of art works in the great museums? Still, the Nazis waltzed out of Paris with hundreds if not thousands of paintings… Do you think many of them were ultimately destroyed or lost during this time period?

The Germans – inspired by Hitler and Goering – helped themselves to thousands of works of art, but the overwhelming majority of these were taken from Jewish collections and not French museums. The Louvre and other leading museums were emptied of their paintings – most large statues had to remain – and these were placed in rural chateaux, but the Germans knew where they were (one exception is Mona Lisa which was kept hidden until the liberation). Of the Jewish-owned art that left France, some of the major collections, such as that of the Rothchschilds, were recovered and restituted after the war. But several thousand works brought back to France in the late 1940s were never returned to their owners. In fact, only after Hector Feliciano denounced France’s minimal efforts to restitute this art in his book The Lost Museum: The Nazi Conspiracy to Steal the World’s Greatest Works of Art did the French government begin to advertise the existence of “looted” art in its museums.

The degenerate art exhibition (entartete Kunst) shown in Munich in 1937 was a reaction, among other notions, against Modernism. The Nazis attempted to purify art… yet as the war churned on, and the Nazis obviously attempted to control French cultural output, they didn’t exactly stamp out what was then the center of Modernist creation. What’s your take on the historical task the Nazis set themselves up for and yet couldn’t quite manage?

Hitler and Goering were interested principally in Renaissance and post-Renaissance northern European art and they took what they wanted from Jewish collections to fill their planned museums. But since the Nazis were grabbing everything they could find belonging to Jews, they also collected a large quantity of Modern art, much of its classified by them as “degenerate.” There is one report of several hundred such works being destroyed by fire outside the Jeu de Paume in Paris, but Nazis often preferred to exchange or sell works by the likes of Picasso, Klee or Kandinsky. Fauvist art had also been included in the Entarte Kunst exhibition, but, as noted, leading Fauvist painters like Vlaminck and van Dongen were “forgiven” when they agreed to travel to Germany. Still, apart from Picasso, Braque, Dufy, Bonnard and others continued to work and exhibit and a new generation of abstract artists first made its appearance in small discreet shows in Paris during the occupation. In other words, when the liberation came, Modernism soon followed.

The rise of Soviet Socialist Realism, or “tractor art” in both the USSR and China, was a marriage of artists and politicians with the goal of strengthening society… What were the equivalents that stand out for you in Nazi-occupied Paris? From the French or the Nazi point of view?

The Vichy regime felt that artists could contribute to France’s moral rebirth and it promoted music, dance and theater to this end. But, for instance, when artists belonging to a nationwide cultural movement called Jeune France began displaying too much independence, the organization was hurriedly closed. In practice, apart from writers like Brasillach and Drieu La Rochelle who spouted pro-Nazi propaganda as journalists and those like Céline who spewed anti-Semitic venom in all directions, there was almost no political – in the sense of pro-Nazi or pro-Vichy – art created between 1940 and 1944. In fact, even in movies, apart from propaganda newsreels, there were no more than two blatantly pro-fascist films among the 220 released during the occupation. Somehow the aesthetics of occupation never caught on.

How would you assess contemporary French art (and writing) 70 years later… are there traces of this legacy?

Evidently both French art and literature have failed to recover their pre-war glory. In the case of art, the lead passed initially to New York, but now it is shared by many other cities, with Paris still lagging behind as a motor of contemporary art. With literature, I believe that French writing is only just recovering from the impact of the Nouveau Roman which, from the 1950s, gave stylistic experimentation precedence over narrative. That said, not all is lost in French culture! The New Wave cinema of the late 1950s and 1960s demonstrated that French creativity was alive in other art forms. To this I would add dance because, while the likes of Merce Cunningham and Martha Graham led the way in transforming contemporary dance, French choreographers and companies have proven talented disciples. And, by the way, the Paris Opera Ballet is rightly considered one of the world’s best classical dance companies.

Do you believe that New York and London are the aesthetic victors of a war fought more than half a century ago? Or has the very idea of contemporary creation resisted national borders and gone “wifi” – that is, international, decimating the need for some kind of national cultural, aesthetic creation?

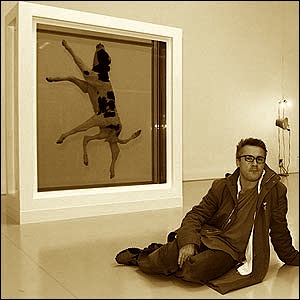

The true victor in any aesthetic post-war “war” has of course been American popular culture which is now so engrained around the world that everywhere it blends with local cultures to reproduce itself in new forms. Conversely, national cultures take on international characteristics so that world music was merely the first in a long line of world arts, such as world movies, world conceptual art, world architecture, etc. Artists like to win recognition in, say, New York or London because both cities have media that can multiply the impact of their success. And in the case of visual artists, the auctions in New York and London are still those that bring the highest prices. In other words, money and recognition go hand-in-hand. And as evidence of this, I would say no more than Damien Hirst. Had he been French, without a scandalous tabloid press willing to draw attention to his gimmicks, without a collector like Charles Saatchi eager to speculate in art, without a City of London swimming in cash, he would have remained a peripheral figure. Instead, Hirst became a commercial phenomenon in which Being Damien was more important than any art he created. Then the money ran out in Britain, the Damien bubble burst and it was time to look elsewhere for new fashionable artists. Shanghai? Mumbai? São Paulo? Why not? Just follow the money. And, as we all know, money no longer has borders.