High Society at the Wellcome Collection through February 27 is a fascinating look at the cultural history of mind-altering drugs as used by a broad range of societies; its approach is remarkably non-judgmental. The introductory text explains Every society on Earth is a high society. Very few people live their lives without using some sort of mind-altering substance, whether it’s a cup of coffee, a chew of betel nut or a tablet of MDMA (ecstasy).

The exhibition includes actual drugs in various forms (a ball of opium – the form in which the British East India Company transported it, bottle of heroin, early patent medicines containing laudanum, a peyote cactus), documents, books (scientific and literary), printed ephemera (such as posters for temperance campaigns), drug paraphernalia, and a range of art including drawings, paintings, sculpture, photography and video. I can think of no comparable U.S. public collection that might take a similar approach to drug use – neither condemning nor sensationalizing – although David Rubin organized an exhibition related to part of the topic last year at the San Antonio Museum of Art, Psychedelic: Optical and Visionary Art since the 1960s.

The initial display is a large wall case containing a variety of drug paraphernalia including bongs, hookahs, coffee pots, beetle-nut scissors and a bowl for grinding kava; perhaps I should mention here that the labels mounted on the wall, 8 feet behind the viewers, give some indication that following the text is going to be hard work. Someone also had the bad idea of numbering the objects in each case or section beginning with number 1, rather than numbering the entire exhibition sequentially; but it is truly worth the annoyance to follow them along with the further information supplied in a free, printed booklet. The exhibition is likely to be mind-expanding for all visitors, given its broad scope.

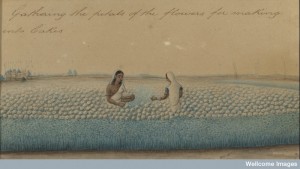

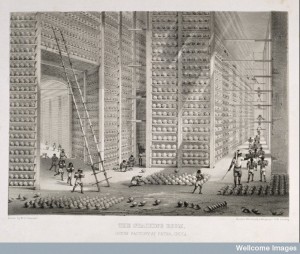

Among the exhibition’s more interesting approaches is to ground the cultural use of drugs within global economic history. An initial section on the drug trade includes a series of 19th century watercolors (above) of the stages in agricultural cultivation of the opium poppy, while a series of lithographs documents an opium factory (below). The production was industrial in scale; this was not the village product of an undeveloped country but the economic underpinning of Britain’s colonial empire, developed to maintain its influence in China. A large sculpture, Frolic (2008) by Huong Yong Ping takes the form of a gigantic opium pipe on which sits a toppled statue of Palmerston, the British Foreign Secretary who defended Britain’s import of the illegal opium into China on the basis of free trade.

The central section covers self-experimentation with drugs by scientists (who regularly tested new medications on themselves) and a range of artists. It includes manuscripts of both de Quincy’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater and Coleridge’s opium-induced Kubla Kahn (not penned under the influence, if the neat handwriting is any indication), drawings by the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot under the influence of hashish and Henri Michaux on mescalin, and Rodney Graham’s video, Photokinetoscope (2001) showing him cycling around a public garden in Berlin while on LSD. I’d been attracted to the exhibition on reading of Bryan Gysin’s Dream Machine, intended to produce hallucinations without the use of drugs. It turned out to be a rather modest version of Duchamp’s Roto-Reliefs (with a vertical tube rather than a flat disc), but intended to be stared at through closed eyelids. I probably didn’t give it enough time, for no hallucinations came.

There was also the chance to see Tate’s version of that iconic image, Richard Hamilton’s Swinging London, based on a news photo of the arrest of Mick Jagger and his dealer for marijuana possession. The painting exists in six versions, but the Tate’s is the only one with collage elements; Hamilton brilliantly depicted the handcuffs in polished aluminum, creating reflections which evoke the flash of the paparazzi’s cameras.

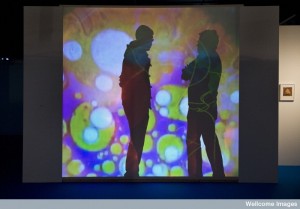

A section on the communal use of drugs ranges from anthropological films of the Tukano people of the Colombian Amazon who use hallucinogens in healing rituals and the Waika palm fruit festival in Venezuela, which involves hallucinogenic snuff, to The Joshua Light Show, a reproduction of the light shows that its maker, Joshua White, regularly produced for Fillmore East in the 1960s, those gesamkunstwerks of drugs, light and music.

After a section devoted to the question of whether drug use is a crime, vice or disease and various solutions, dependent upon the interpretation, one leaves the exhibition through two large installations. Mustafa Hulusi’s large video installation, Afyon (which is an area of Turkey long devoted to growing opium poppies and the ultimate source for the drug’s name) immerses visitors within lyrical views of poppy fields in various stages of their growth cycle. It evokes the absolute beauty of the untouched flowers, but given the pain of opium addiction and the violence associated with its criminal distribution, it is inevitably bittersweet. Then designer David McCandless has produced two huge wall pieces in the forms of didactic charts of the economics of international drug production and distribution. This returns us to the economic and political complexity of the exhibition’s opening section, and the questionable morality and politics of drug trafficking, legislation and policing.

High Society accepts the fact that mind-altering substances have been used by humans since pre-history and offer sensations that have broad human appeal. While it avoids offering solutions to the unsuccessful attempts to limit drug use through education, legislation and policing, it gives a much more nuanced understanding of drug use than most of its visitors are likely to have, and provides the basis for more rational discussion about dealing with substances which offer so much personal and social appeal, conflict and damage.