By Thomas Devaney

The “Tibor de Nagy Gallery Painter and Poets” exhibition is dream-like. The dream we enter is the salon atmosphere of the gallery’s early days, creating an overall effect of a group portrait of a handful of individuals who reached out to each other through their art. The exhibition reveals how these poets and painters employed numerous strategies to merge into one another’s work while simultaneously shaping their singular creative paths. The enterprising portrait that emerges has been much talked about—and even written about—but has yet, until this retrospective, to be assembled all in one space.

Poet and writer Douglas Crase summons the scene’s headiness:

Our continuing romance with the New York School poets derives in large part from their own romance with the artists of their time, notably the painters of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. With the gallery as a venue, these painters and poets fashioned a ferment of affairs, rivalries, and collaborations that seems to exemplify our bravest bohemian dream of youth. One may suspect it’s a youth that never was. But the suspicion passes; and we are left dreaming anyway of the poet-and-painter pairings: the plays, parties, poem-paintings, and legendary poet-and-painter pamphlets—the Tibor de Nagy Editions—that constituted in each case the poet’s first book.

-From “Unlikely Angel: Dwight Ripley and the New York School.” Essay for pamphlet for Unlikely Angel at Poets House, 2005.

The exhibition generously culls from the major poem-paintings and nearly all of the poet-and-painter pamphlets. The “creation” of the New York School of Poetry by Tibor de Nagy gallery director John Bernard Myers is a central legend. The gallery published 18 limited-edition collections of poetry under its imprint, with covers and interiors illustrated by the de Nagy artists. The show displays first books by Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, James Schuyler, John Ashbery, Barbara Guest, Kenward Elmslie, Bill Berkson and others.

And there is more. The photographs and two films by Rudy Burckhardt celebrate a vanished past; and the many paintings of the era by Fairfield Porter, Helen Frankenthaler, Trevor Winkfield, Nell Blaine, Joe Brainard, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Jane Freilicher and Alfred Leslie are vivaciously free of an overriding house style. It is remarkable that the names and the works all but live up to their various reputations. The viewer experiences the intimate immersion of the milieu, the “channel of introductions, theater of events, and generator of the ambient scene” that Crase ably illuminates in the accompanying catalog.

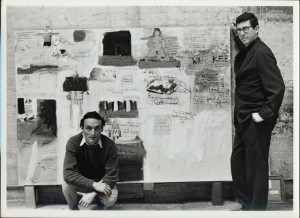

Plenty of expected, actual portraits ground the show, including Fairfield Porter’s big painting of James Schuyler and John Ashbery, several fine portraits by Jane Frelicher, George Schneeman’s intimate depiction of Ron Padgett and Ted Berrigan (the last painting reproduced in the catalog only), and the richly applied paint in Jane Frelicher’s stunning portrait of Nell Blaine. Other such delights include a few of the brash and fresh Oranges series by Grace Hartigan and Frank O’Hara (one dozen Hartigan paintings employing text by O’Hara incorporated into the work) and the rollickingly mixed media piece In Bed by Larry Rivers and Kenneth Koch (picture above).

And indeed, the larger rendering is one of a collaborative moment. Referring to the gallery’s origin story, Holland Cottter’s nuanced review in the New York Times underscores how the show reflects a cultural “golden moment”; but it is a moment that blurs the very idea of a moment and, certainly, challenges our desire for a singular one. Generations haphazardly overlap and their respective moments are mingled. Work in the show spans the early 50’s to the late 70’s. The featured image accompanying Cotter’s review is Larry Rivers’s “Pyrograph: Poem and Portrait of John Ashbery II,” 1977.

The exhibition is a portrait of a collaborative ethos as much as a moment. But another way to put it is that gallery’s original moment dramatizes the work that happens in its orbit over the next three decades.

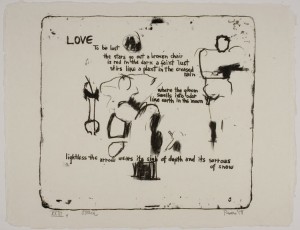

Of all the work in the show, Frank O’Hara’s collaboration with Larry River’s entitled Stones, 1958, was something that I had only ever read about and was eager to see. The suite of lithographs is fully realized. Carter Ratcliff has written that you can almost see “painter and poet trying to snatch the unfinished lithographic stones from each other’s hands.” The handmade energy is in the work. Bill Berkson has written that the suite is one of “the very first ‘hands-on’ poet/painter collaborations (not cadavers exquises of the Surrealists) and probably the most thoroughly successful work ever in that genre.”

The entire show is a play upon expectations and one of connecting the dots. George Schneeman’s collaborations look fresh and contemporary on the wall, and the pleasure of Joe Brainard’s seemingly artless art, grows by the day. But I was practically delighted to see two works by Trevor Winkfield that I thought I had never seen before. The Winkfield’s are eye-opening when one knows them as book covers instead of opened-up art on a gallery wall: one is for Ashhery’s Rivers and Mountains and other for his Three Poems. The minimalist design of these extra-graphic Winkfield’s has a localized snap and pleasure that works beyond the book covers.

Did all of the collaborations bear fruit? No, of course not. One intriguing set of letters charts an unrealized project between John Ashbery and Joe Brainard. It is an instructive curatorial decision to include these letters, and to read that not everything always worked out. In 1966, Ashbery and Brainard began a book-length cartoon collaboration. Ashbery sent Brainard pieces of text as well as some clippings from comics, and Brainard was to draw a cartoon in response, using Ashbery’s words. The book was never completed.

The Brainard-Ashbery puts the dream of the realized work in context, but the atmosphere of most of the art here remains. One private experience I had while looking at the show was to discover a piece that Joan Mitchell made with James Schuyler in 1975. The interior spun light of Mitchell’s Daylight is a perfectly restrained correlative for the moment of Schuyler’s poem “Daylight.” He writes:

And when I thought,

“Our love might end”

the sun

went right on shining.

* “Dawn breaks thousands of windows in the city” is a line from John Ashbery’s The Poems, collaboration with Joan Mitchell (Tiber Press, 1961).

Tibor de Nagy Gallery Painters and Poets, to Saturday, March 5. Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York

–Thomas Devaney is the author of A Series of Small Boxes (Fish Drum). He is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Haverford College and editor of the e-journal ONandOnScreen poems + videos. Visit his website.