As her third solo exhibition at Locks Gallery, The Home Front: Jane Irish’s Art of War continues a ten-year investigation of anti-war resistance. On view from February 4 to March 12, the exhibition brings together various perspectives on the Vietnam War through Irish’s appropriation of poetry from a Vietnamese civilian and American war veterans.

Much of the artist’s research comes from speaking with local veterans, especially those who identify as Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Additionally, Irish spent two summers painting in Vietnam, where she was introduced to the work of Vietnamese poet Ho Xuan Huongs through the translation of John Balaban. Balaban is also the founder of the Nom Preservation Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving the vernacular script and poetic history of Vietnam prior to its banishment by the French colonial government in the seventeenth century.

This period of colonial suppression also coincides with the Rococo period depicted in Irish’s lavish interiors. In “Room with Green Boiseries,” 2010, paintings are arranged salon-style and appear to extend into the ceiling. Complete with opulent furnishings, adornments, and no less than five chandeliers, the room gives no sign of external conflict. Instead, the Rococo interior remains isolated and symbolic of French and later, American imperialists.

The ceramic vases in the exhibit are as beautiful and seductive as Irish’s paintings of lavish interiors and, at first glance, they too mask any sense of political unrest. Upon closer examination, though, scenes of upheaval and protest become apparent. Vignettes of soldiers and civilian protesters, the United States and Vietnam, and the past and the present are juxtaposed, giving voice to the conflict’s multiple perspectives and offering a comprehensive view.

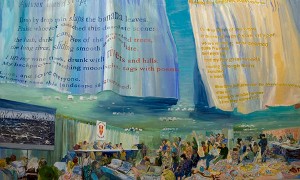

Yet, it is the artist’s inclusion of poetry from Ho Xuan Houngs and Vietnam Veterans Against the War that makes this focus on multiple perspectives most apparent. In “The Conversation,” 2010, Irish appropriates poetic works from both parties and creates a discussion between Ho Xuan Houngs and VVAW members that looks at the colonial history of Vietnam and the war’s aftermath. Measuring thirty feet wide, “The Conversation” is the exhibition’s largest work. Texts from both parties float in banners above the Vietnam landscape, lending the work a mural-like presence. By bringing together such disparate viewpoints at this scale, the artist forces one to consider the conflict.

Although Irish’s show remains focused on providing multiple perspectives to form a global view, her identification with grassroots activism is most evident in “Winter Soldier in 1971,” 2010. Again, the artist juxtaposes poetry from Ho Xuan Houngs and Vietnam Veterans Against the War by placing two banners over a meeting of VVAW in

Detroit. Unlike Irish’s paintings of Rococo interiors, the room is dynamic and filled with participants. For Irish, this anti-war resistance at the local level is the most powerful way to combat global conflict and her reason for focusing on the home front.